Vasculitis is a group of disorders that destroy blood vessels by inflammation.B oth arteries and veins are affected. Lymphangitis is sometimes considered a type of vasculitis. Vasculitis is primarily caused by leukocyte migration and resultant damage.

Vasculitis is a complex illness. This spectrum of conditions involving blood vessel inflammation usually has unknown causes — and symptoms can be hard to pin down. The good news is that doctors are making strides in their understanding of these diseases with better drug therapies.

Rheumatologist says that vasculitis can affect anyone of any age and can result in damage to organs and blood vessels over time. It was once considered fatal, but thanks to medical advances, vasculitis is now manageable as a chronic condition in many cases.

[dropshadowbox align=”none” effect=”lifted-both” width=”auto” height=”” background_color=”#ffffff” border_width=”1″ border_color=”#dddddd” ]

Definition of vasculitides adopted by the 2012 Chapel Hill Consensus Conference on the nomenclature of vasculitis

| Large‐vessel vasculitis (LVV) | |

| Vasculitis affecting large arteries more often than other vasculitides. Large arteries are the aorta and its major branches. Any size artery may be affected |

| |

| Medium‐vessel vasculitis (MVV) | |

| Vasculitis predominantly affecting medium arteries defined as the main visceral arteries and their branches. Any size artery may be affected. Inflammatory aneurysms and stenoses are common |

| |

| Vasculitis predominantly affecting small vessels, defined as small intraparenchymal arteries, arterioles, capillaries, and venues. Medium arteries and veins may be affected |

| ANCA‐associated vasculitis (AAV) | |

| Necrotizing vasculitis, with few or no immune deposits, predominantly affecting small vessels (ie, capillaries, venules, arterioles, and small arteries), associated with myeloperoxidase (MPO) ANCA or proteinase 3 (PR3) ANCA. Not all patients have ANCA. Add a prefix indicating ANCA reactivity, eg, MPO‐ANCA, PR3‐ANCA, ANCA negative |

| |

| |

| Immune complex vasculitis | |

| Vasculitis with moderate to marked vessel wall deposits of immunoglobulin and/or complement components predominantly affecting small vessels (ie, capillaries, venules, arterioles, and small arteries). Glomerulonephritis is frequent |

| |

| |

| |

| Variable vessel vasculitis (VVV) | |

| Vasculitis with no predominant type of vessel involved that can affect vessels of any size (small, medium, and large) and type (arteries, veins, and capillaries) |

| |

| Single organ vasculitis (SOV) | |

| Vasculitis in arteries or veins of any size in a single organ that has no features that indicate that it is a limited expression of systemic vasculitis. The involved organ and vessel type should be included in the name (eg, cutaneous small vessel vasculitis, testicular arteritis, central nervous system vasculitis). Vasculitis distribution may be unifocal or multifocal (diffuse) within an organ. Some patients originally diagnosed as having SOV will develop additional disease manifestations that warrant redefining the case as one of the systemic vasculitides (eg, cutaneous arteritis later becoming systemic polyarteritis nodosa, etc.) |

| |

| |

| |

| Others | |

| |

| Vasculitis that is associated with and may be secondary to (caused by) a systemic disease. The name (diagnosis) should have a prefix term specifying the systemic disease (eg, rheumatoid vasculitis, lupus vasculitis, etc.) |

| |

| |

| |

| Others | |

| |

| Vasculitis that is associated with a probable specific etiology. The name (diagnosis) should have a prefix term specifying the association (eg, hydralazine‐associated microscopic polyangiitis, hepatitis B virus‐associated vasculitis, hepatitis C virus‐associated cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, etc.) |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Others | |

Types of Vasculitis

[dropshadowbox align=”none” effect=”lifted-both” width=”auto” height=”” background_color=”#ffffff” border_width=”1″ border_color=”#dddddd” ]

[/dropshadowbox]

www.rxharun.com

According to the Johns Hopkins Vasculitis Center, “There are approximately 20 different disorders that are classified as vasculitis.

According to the size of the vessel affected, vasculitis can be classified into

- Large vessel – Polymyalgia rheumatica, Takayasu’s arteritis, Temporal arteritis

- Medium vessel – Buerger’s disease, Kawasaki disease, Polyarteritis nodosa

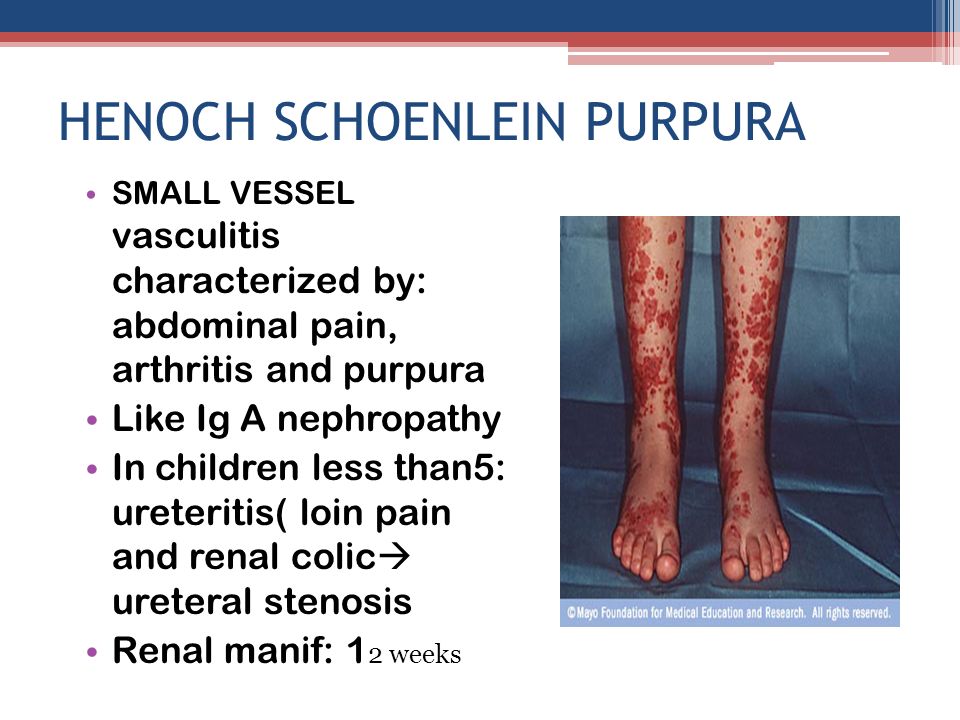

- Small vessel – Behçet’s syndrome, Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, Cutaneous vasculitis, Henoch–Schönlein purpura, Microscopic polyannulomatosisConditionofSome disorders have vasculitis as their main feature.

[dropshadowbox align=”none” effect=”lifted-both” width=”auto” height=”” background_color=”#ffffff” border_width=”1″ border_color=”#dddddd” ]

The major types are given in the table below:

| Comparison of major types of vasculitis | ||

|---|---|---|

| Vasculitis | Affected organs | Histopathology |

| Cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis | Skin, kidneys | Neutrophils, fibrinoid necrosis |

| Granulomatosis with polyangiitis | Nose, lungs, kidneys | Neutrophils, giant cells |

| Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis | Lungs, kidneys, heart, skin | Histiocytes, eosinophils |

| Behçet’s disease | Commonly sinuses, brain, eyes and skin; can affect other organs such as lungs, kidneys, joints | Lymphocytes, macrophages, neutrophils |

| Kawasaki disease | Skin, heart, mouth, eyes | Lymphocytes, endothelial necrosis |

| Buerger’s disease | Leg arteries and veins (gangrene) | Neutrophils, granulomas |

| “Limited” granulomatosis with polyangiitis vasculitis | Commonly sinuses, brain, and skin; can affect other organs such as lungs, kidneys, joints; | |

[/dropshadowbox]

There are a number of different names for subtypes of vasculitis depending on which parts of the body are affected. These include the conditions called

- Systematic vasculitis — When several different organs are affected due to multiple inflamed arteries. This usually causes widespread symptoms that affect the whole body.

- Cogan’s syndrome — Describes the type of vasculitis that affects large blood vessels, especially the aorta and aortic valve (the main artery that carries blood away from your heart to the rest of your body).

- Polyarteritis nodosa— When inflammation occurs in medium-sized arteries throughout the body.

- Autoimmune inflammatory vasculitis — this is when someone has an existing autoimmune disorder that causes the immune system to attack the body’s own tissue (such as lupus, rheumatoid arthritis or scleroderma) and then develops vasculitis.

- Takayasu arteritis — When inflammation occurs in the aorta, vessels connecting the aorta and pulmonary arteries.

- Behcet’s disorder — Chronic inflammation that causes recurrent mouth sores.

- Churg-Strauss syndrome — Inflammation of the blood vessels in the lungs, sinuses and nasal passageways which commonly happens in people with asthma.

- Giant cell arteritis — Inflammation of the blood vessels in the upper body including the head, temporal lobes and neck.

- Henoch-Schonlein purpura — Inflammation of the blood vessels in the skin, kidneys, and intestines.

- Microscopic polyangiitis — Inflammation of the small arteries in the lungs and kidneys.

- Wegener’s granulomatosis — Inflammation of the small arteries in the sinuses, nose, lungs, and kidneys.

Symptoms of Vasculitis

[dropshadowbox align=”none” effect=”lifted-both” width=”auto” height=”” background_color=”#ffffff” border_width=”1″ border_color=”#dddddd” ]

| Size of blood vessel | Blood vessel involved | Clinical features |

|---|---|---|

| Small vessel vasculitis (vessels smaller than arteries such as capillaries and venules) | Cutaneous post‐capillary venules | Palpable purpura |

| Glomerular capillaries | Haematuria, red cell casts in urine, proteinuria, and decline in renal function | |

| Pulmonary capillaries | Lung haemorrhage manifesting as breathlessness, haemoptysis and widespread alveolar shadowing on chest radiograph | |

| Medium vessel vasculitis (small and medium sized arteries) | Small cutaneous arteries | Necrotic lesions and ulcers, nail fold infarcts |

| Epineural arteries | Mononeuritis multiplex | |

| Mesenteric artery | Abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation because of gut infarction | |

| Branches of coeliac artery | Infarction of liver, spleen, or pancreas | |

| Renal artery | Renal infarction | |

| Coronary arteries | Myocardial infarction or angina, coronary artery aneurysm, ischaemic cardiomyopathy | |

| Small pulmonary arteries | Necrotic lesions leading to cavitating lung shadows on chest radiograph | |

| Small arteries in ear, nose and throat region | Nasal crusting, epistaxis, sinusitis, deafness, stridor because of sub‐glottic stenosis | |

| Large vessel vasculitis (aorta and its branches) | Extracranial branches of carotid artery | Temporal headache (temporal artery), blindness (ophthalmic artery), jaw claudication (vessels supplying muscles of mastication) |

| Thoracic aorta and its branches | Limb claudication, absent pulses and unequal blood pressure, bruits, thoracic aortic aneurysms |

[/dropshadowbox]

What makes treating vasculitis a challenge? Here are a few reasons:

- There are several different types of vasculitis

- Even within a specific disease, the features differ among patients

- Many organs and/or blood vessels are affected

- Some forms are mild, others severe

- It can be secondary to an underlying condition

- It can be a primary disease with an unknown cause

Depending on the person, vasculitis symptoms can include

- Fever symptoms like dizziness, loss of appetite, fatigue, sweating, nausea, etc.

- Weight loss or weight changes due to digestive issues.

- Nerve damage or unusual nerve sensations. This may include numbness, tingling, weakness or “pins and needles.”

- Cognitive changes, including mood-related problems, confusion, trouble learning, etc.

- Higher risk for hemorrhages, seizures or stroke.

- A skin rash or discoloration of the skin. This may include the skin appearing bumpy, developing sores or ulcers (especially on the lower legs), or appearing dark due to hemorrhaging that results in bluish-red bumps.

- Digestive problems, including stomach pains, diarrhea, bloody stool, nausea and vomiting.

- Heart problems, such as high blood pressure, heart arrhythmia, angina or higher risk for heart attacks.

- Kidney problems including fluid retention (edema), dysfunction and kidney failure.

- Muscle pains, joint pains, inflamed joints, swelling and trouble moving normally.

- Coughing, shortness of breath, chest pains and trouble exercising due to difficulty breathing.

- Mouth sores or sores on the genitals.

- Ear infections.

- Headaches.

- Higher risk for blood clots.

- Problems with vision and developing painful, irritated eyes.

- In rare cases, life-threatening complications can develop that affect the heart, kidneys and lungs when a person does not respond to treatment.

- Some people also experience secondary mental health problems like fear, anxiety, depression and stress due to feeling overwhelmed by their condition. This can lead to decreased quality of life if it’s left untreated.

“One type of vasculitis is known as giant cell arteritis, which primarily affects elderly patients,” he says. “It usually presents with new headaches and pain in your jaw while eating. Another type affects your lungs, causing you to have shortness of breath and to cough up blood. There are also forms of vasculitis that can cause big, swollen and painful joints.”

Local symptoms

Local symptoms are featured by the simultaneous (or sequential) appearance of symptoms from different affected organs in a patient with vasculitis syndrome.

- Visceral Signs/Symptoms of Large‐ and Medium‐Vessel Vasculitis. As large to medium‐sized blood vessels run from the aorta to the organs, the signs/symptoms of vasculitis result from injury to organs supplied by the affected vessels. These signs/symptoms include pulse deficit, jaw claudication, loss of vision, and acute abdomen. Especially in large‐vessel vasculitis, clinicians should be aware of the possibility that any size of the artery may be affected, because a decrease in aortic blood pressure can result in compromise of blood flow to all downstream arteries.

- Visceral signs/symptoms of Small‐Vessel Vasculitis. In cases with skin rash, the so‐called palpable purpura is a distinguishing feature that frequently develops in the lower limbs. Mononeuritis multiplex is a clinical manifestation of vasculitis of medium to small arteries that feed the affected nerves. In the early stage, it may manifest as sensory disturbance, such as hyperesthesia or hypoesthesia, and, when progressive, leads to motor disturbance that may result in drop hand or foot. The clinical features of small‐vessel vasculitis in the kidney include those of nephritides, such as hematuria, proteinuria, and cylindruria. In some cases, pulmonary alveolar hemorrhage caused by arteriolitis or venulitis in the lungs develops with bloody and foamy sputum.

Laboratory findings and imaging studies

- General Laboratory Findings – Acute inflammatory markers, such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), CRP, and white blood cell (WBC) count, may be present. In cases with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), a significant increase in eosinophil is observed. At times, high level of plasma renin activity or HBV antigen positivity can be seen in a patient with polyarteritis nodosa (PAN).

- Urinalysis – Even in its early stage, proteinuria, erythruria, leukocyturia, and cylindruria can be found in patients with microscopic polyangiitis (MPA). However, in PAN and granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), there are cases in which abnormal urinary findings appear over time rather than immediately.

- Biochemical markers – In MPA, PAN, and GPA, renal dysfunction, such as elevation of serum creatinine, a rise in BUN, and a decline in creatinine clearance, can be observed. As interstitial pneumonia is one of the representative clinical features in MPA, a rise in KL‐6 can also be seen.

- Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) – In MPA and EGPA, it is common (50%‐80% of cases) to detect myeloperoxidase (MPO)‐ANCA (perinuclear [p] staining pattern with an indirect immunofluorescent [IIF] assay, p‐ANCA). Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody testing is usually negative in PAN (<20% ANCA positive). In GPA, proteinase 3 (PR3)‐ANCA (cytoplasmic (c) staining pattern with IIF assay, c‐ANCA) is positive (90%). In recent years, genetic factors,[rx]biological environment factors (the induction of neutrophil extracellular traps from neutrophil caused by bacterial infections),[rx] scientific environment factors (antithyroid drugs, such as propylthiouracil,7 atmospheric environmental chemicals such as silica) have been presumed as causes of ANCA positivity. Detailed history taking via an interview is highly important to distinguish primary vasculitis from genetic or environmental factor‐associated vasculitis in a patient with positive ANCA and equivocal clinical features of vasculitis.

- Antiglomerular basement membrane (GBM) antibody – Especially in cases exhibiting RPGN and/or alveolar hemorrhage, it is essential to suspect anti‐GBM disease. Serum anti‐GBM antibody is specific to laboratory findings for the anti‐GBM disease. Although there are various methods to detect anti‐GBM antibodies, such as the IIF assay, hemagglutination assay, radioimmunoassay (RIA) method, and enzyme‐linked immunoassay (ELISA) method, the RIA and ELISA method have superior sensitivity (>95%) and specificity (>97%).[rx[

- Imaging study – Plain radiographs of the chest and paranasal sinuses, ultrasonography, CT, MRI, and thermography have been used to confirm abnormal vascular wall structure and blood flow dysfunction. If acute‐phase Takayasu disease (TAK) is present, aortic wall thickening will be densely stained with gadolinium on contrast‐enhanced MRI. As MRA can clearly outline whether or not there are any irregularities, contractions, or occlusion of the vascular walls, this imaging modality is often useful for interpretation of symptoms related to ischemia. Further, it may be possible to localize aortic inflammation using 18F‐fluorodeoxyglucose‐positron emission tomography (FDG‐PET). Increased glycolytic metabolism in inflammatory tissues or malignant tumors is the rationale behind the common use of FDG‐PET.[rx] Diagnostic imaging studies of the thorax (X‐rays, CT, MRI) may show interstitial infiltrative shadows in the lung field in a patient with MPA.

- Granulomatous lesions – can also be accompanied by infiltrative shadows in patients with EGPA and GPA. PAN can cause multiple microaneurysms and/or contractions in association with inflammation of medium‐sized and small arteries. Aneurysms can be frequently detected in the branches of the abdominal aorta (eg, renal, mesenteric, and hepatic arteries) and can be confirmed via angiography. However, aneurysms are usually not detected during the acute phase. In some cases, it is possible to detect impaired blood flow using MRA or the ultrasonic Doppler method. However, in Japan, some physicians tend to avoid conventional angiography because of its invasiveness and because PAN can typically be diagnosed via biopsy.

- Physiological tests – electrocardiography (ECG), pulse‐wave detection, electroencephalography (EEG), electromyography (EMG), and nerve conduction studies are important for the diagnosis of vasculitis syndrome and to classify its severity. EMG and nerve conduction studies are crucial for the diagnosis of latent vasculitis syndrome and to identify appropriate biopsy sites.

Tissue biopsy

- With regard to small‐vessel vasculitis, it is essential to test for ANCA and immune complexes. However, these are definitive factors for diagnosis; rather, tissue biopsy is the most important diagnostic method for the vasculitic syndrome. If it is necessary to differentiate ANCA‐associated vasculitis (AAV) from immune complex‐mediated vasculitis, it is preferable to prepare the materials for IIF staining in advance before conducting the tissue biopsy. Because the primary lesions of TAK are in the aorta and those of Kawasaki disease (KD) are in the coronary arteries, it is not possible to perform a biopsy for diagnosis of these diseases. Hence, in such cases, diagnostic imaging study plays a central role in diagnosis. For other primary vasculitis syndromes, biopsy of the affected vessels is the most useful method for diagnosis.

Some considerations with regard to tissue biopsy for systemic vasculitis are as follows

- Giant cell arteritis (GCA) – A biopsy of the temporal artery is essential for diagnosis. As noncontiguous segmental lesions develop in GCA, it is crucial to prepare serial sections of biopsy specimens.[rx]

- PAN – Although the typical histological finding of PAN is necrotizing angiitis, which is characterized by fibrinoid necrosis in the tunica media, old and new lesions are often observed within the same tissues. By definition, PAN does not include inflammation of the arterioles, venules, and capillaries, meaning that PAN is not associated with glomerulonephritis.

- MPA – The typical histological finding of MPA is necrotizing angiitis in arterioles and capillaries in the kidneys, indicating necrotizing crescentic glomerulonephritis.

- GPA – A finding of necrotizing granulomatous lesions with giant cells in lesion sites of the upper respiratory tract (eg, nose, paranasal sinuses, and soft palate) is useful for early diagnosis. Various patterns of glomerulonephritis can also be found in kidney biopsy specimens.

- EGPA – Biopsy specimens from peripheral nerves, muscles, and lungs with infiltration show vasculitides and granulomas with prominent invasion with eosinophils.

- Anti‐GBM Disease – Diffuse crescentic glomerulonephritis is a distinctive feature of this disease. IIF staining can show deposition of IgG and C3 along the glomerular capillary walls.

- IgA vasculitis (IgAV) – Necrotizing angiitis can be observed with blood vessels in the area from the papillary layer to the reticular layer of the skin. Using immunofluorescent staining, in accordance with the areas where necrotizing angiitis has occurred, deposition of IgA in areas from the vascular endothelial cells to the vascular lumen can be observed.

[dropshadowbox align=”none” effect=”lifted-both” width=”auto” height=”” background_color=”#ffffff” border_width=”1″ border_color=”#dddddd” ]

Other symptoms run the gamut and may include nasal congestion, nose bleeds, mouth ulcers, hearing loss, skin lesions, vision problems, numbness, weakness, cough, shortness of breath, fever and unexplained weight loss.

| Disease | Serologic test | Antigen | Associated laboratory features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | ANA including antibodies to dsDNA and ENA [including SM, Ro (SSA), La (SSB), and RNP] | Nuclear antigens | Leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, Coombs’ test, complement activation: low serum concentrations of C3 and C4, positive immunofluorescence using Crithidia luciliae as substrate, antiphospholipid antibodies (i.e. anticardiolipin, lupus anticoagulant, false-positive VDRL) |

| Goodpasture’s disease | Anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody | Epitope on noncollagen domain of type IV collagen | |

| Small vessel vasculitis | |||

| Microscopic polyangiitis | Perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody | Myeloperoxidase | Elevated CRP |

| Granulomatosis with polyangiiitis | Cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody | Proteinase 3 (PR3) | Elevated CRP |

| Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis | perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody in some cases | Myeloperoxidase | Elevated CRP and eosinophilia |

| IgA vasculitis (Henoch-Schönlein purpura) | None | ||

| Cryoglobulinemia | Cryoglobulins, rheumatoid factor, complement components, hepatitis C | ||

| Medium vessel vasculitis | |||

| Classical polyarteritis nodosa | None | Elevated CRP and eosinophilia | |

| Kawasaki’s Disease | None | Elevated CRP and ESR |

In this table: ANA = Antinuclear antibodies, CRP = C-reactive protein, ESR = Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate, dsDNA = double-stranded DNA, ENA = extractable nuclear antigens, RNP = ribonucleoproteins; VDRL = Venereal Disease Research Laboratory

[/dropshadowbox]

Treatment of Vasculitis

Treatment options vary among the different types of vasculitis. Doctors treat almost all types with a glucocorticoid medication, such as prednisone. For certain types of vasculitis, another medication in addition to prednisone is needed.

- “Once we determine the type of vasculitis you have, we look at its severity, which helps us gauge how aggressive we need to be with your treatment and what medications to consider,” Dr. Brown says. “We also have to consider the side effects.”

- It’s important to note that medications that treat vasculitis suppress the immune system, and they increase your risk of infections. You want to consider ways to reduce this risk.

Commonly used drugs

Here are some of the more commonly used medications. However, not every one of them applies to all types of vasculitis or to each individual person. In addition, there are other medications that your doctor may prescribe for vasculitis beyond those listed below.

- The side effects that are included below are not intended to be complete. People should review their treatment plan carefully with their doctor and pharmacist to understand the risks of their medications and what can be done to monitor for and prevent side effects.

1. Prednisone

Prednisone is a glucocorticoid medication (also called a steroid). Glucocorticoids are very valuable in the treatment of vasculitis as they have very broad effects on inflammation and are rapidly acting.

- Treatment details: Glucocorticoids are used in almost all forms of vasculitis. They can be given by mouth or by vein. The initial dosage will be determined by your doctor based upon many factors including the type of vasculitis and the severity of the vasculitis. Usually, this is started at a higher dose and then reduced. Prednisone is a relative of a natural body hormone called cortisol which our body delivers in the morning. Because of this, we ideally give prednisone once a day in the morning to replicate what the body does naturally.

- Side effects: Increased infection risk is the number one concern with prednisone. Other prominent side effects include increased blood sugar (diabetes), increased blood pressure, loss of bone density (osteoporosis), easy bruising, and poor healing. Prednisone is also associated with increased appetite and weight gain and can result in mood swings and insomnia. People taking prednisone also notice a change in appearance related to redistribution of normal fat cells in the face and trunk which usually improves as the dose is lowered.

2. Rituximab (also called Rituxan)

Doctors have used rituximab to treat rheumatoid arthritis patients, with good results. Since 2011, it has also been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of two forms of vasculitis – granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s) and microscopic.

- Treatment details: Rituximab is given by vein in an infusion center or hospital. The treatment time (infusion) takes four to six hours, or longer in some cases. The dose and frequency of rituximab will be determined by your doctor based on a number of different factors.

- Side effects: The main side effects of rituximab are reactions during the infusion, rashes and sores of the skin and mouth. An extremely rare described event is a type of brain virus infection called PML.

3. Cyclophosphamide (also called Cytoxan)

Cyclophosphamide is a tried-and-true older drug, taken orally or intravenously, that doctors also use to treat cancer. It is currently given mainly in the setting of severe small- and medium-vessel vasculitis.

- Treatment details: Taken orally, the typical daily dose is 1.0 to 2.0 milligrams per kilogram of body weight that should be taken all at once in the morning. Throughout the day people should drink a large amount of fluid which helps to flush the medication out of the body in the urine so it is not sitting in the bladder. If your doctor administers the drug intravenously, he or she will determine the dosage based on, your height, weight, and kidney function levels from what has been used in published studies.

- Side effects: Cyclophosphamide has a number of potentially serious side effects that must be understood before this is taken. As it can lower the blood counts, blood tests are performed every 1-2 weeks. Cyclophosphamide can cause injury to the bladder and potentially bladder cancer. You may experience nausea and/or vomiting which is more common when given by vein. Cyclophosphamide increases the risk of birth defects in pregnant women.

4. Methotrexate

Methotrexate is also used to treat many different autoimmune conditions, including vasculitis. This drug is also used to treat cancer, but the dose used to treat cancer patients is several times higher.

- Treatment details: Methotrexate is taken once a week. This drug comes in 2.5-milligram tablets. Your doctor will base the dosage on what has been successfully used in studies, as well as your weight and other factors. The drug can also be given as an injection just under the skin, which some people prefer.

- Side effects: You may experience nausea or vomiting. Mouth sores, rash or diarrhea may occur in a small percentage of cases. Methotrexate can be associated with lowering of the blood counts, irritation of the lungs (called pneumonitis), and liver injury. It is important to avoid drinking alcohol while taking methotrexate. Avoidance of pregnancy is essential as methotrexate can cause miscarriages and birth defects. Your doctor will order blood tests to monitor your blood counts and liver function abnormalities show up in the tests.

5. Azathioprine (also called Imuran)

Doctors mainly use azathioprine as what is referred to as a maintenance medication in people with small- or medium-vessel vasculitis after the vasculitis has been controlled.

- Treatment details: Prior to beginning treatment, doctors usually perform a blood test called TPMT which is a natural body enzyme which breaks down the medication. People who do not make this enzyme cannot take azathioprine and people who make lower amounts will need to be treated cautiously with a smaller dose. In those who have a normal TPMT test, the dosage is usually based on your body weight. You may receive a single or twice-daily dose.

- Side effects: You may experience nausea and vomiting and, in some cases, abdominal cramping or diarrhea. Taking the drug twice a day instead of all at once, or taking it with meals helps some people avoid these side effects. Azathioprine is associated with lower blood counts and abnormal liver tests, which makes regular blood test monitoring is important. Rarely, people may have an allergic reaction to azathioprine that requires the medication to be stopped.

Research associate with vasculitis

Cutaneous Leukocytoclastic Angiitis

Small-vessel vasculitis may be confined to the skin. The characteristic acute lesion is leukocytoclastic angiitis involving dermal postcapillary venules. This lesion is histologically identical to dermal lesions occurring as a component of systemic small-vessel vasculitis. Therefore, the onus is on the physician to rule out systemic disease.

- Drug-induced vasculitis should be considered in any patient with small-vessel vasculitis and will be substantiated most often in patients with vasculitis confined to the skin. Drugs cause approximately 10 percent of vasculitic skin lesions. Drug-induced vasculitis usually develops within 7 to 21 days after treatment begins.

- Drugs that have been implicated include penicillins, aminopenicillins, sulfonamides, allopurinol, thiazides, pyrazolones, retinoids, quinolones, hydantoins, and propylthiouracil. Some drugs, such as penicillins, cause vasculitis by conjugating to serum proteins and mediating immune-complex vasculitis that is similar to serum-sickness vasculitis. Other vasculitis-inducing drugs that cause immune-complex formation are foreign proteins, such as streptokinase, cytokines, and monoclonal antibodies. In addition, such drugs as propylthiouracil and hydralazine appear to cause vasculitis by inducing ANCA, although a cause-and-effect relationship has not been proved.

- Most patients with cutaneous leukocytoclastic angiitis have a single episode that resolves spontaneously within several weeks or a few months. Approximately 10 percent will have the recurrent disease at intervals of months to years. In the absence of systemic disease, management is usually symptomatic. Drugs that could cause the disease should be stopped. Antihistamines and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs help alleviate cutaneous discomfort and reduce associated arthralgias and myalgias. The severe cutaneous disease may warrant oral corticosteroid therapy. If signs or symptoms of systemic vasculitis develop, treatment should be based on the type of systemic vasculitis the patient has.

Henoch–Schönlein Purpura

www.rxharun.com

- Henoch–Schönlein purpura is the most common systemic vasculitis in children. It is characterized by vascular deposition of IgA-dominant immune complexes, and preferentially involves venules, capillaries, and arterioles.

- Henoch–Schönlein purpura is most frequent in childhood, with a peak incidence at five years old. The disease often begins after an upper respiratory tract infection. Purpura, arthralgias, and colicky abdominal pain are the most frequent manifestations. Approximately half the patients have hematuria and proteinuria, but only 10 to 20 percent have renal insufficiency. Rapidly progressive renal failure is rare. Pulmonary disease and peripheral neuropathy are uncommon.

- The overall prognosis is excellent; thus, supportive care suffices for most patients. The main long-term morbidity is from progressive renal disease. The end-stage renal disease develops in approximately 5 percent of patients. Treatment for aggressive Henoch–Schönlein purpura glomerulonephritis is controversial. Corticosteroids, immunosuppressive drugs, and anticoagulant therapy have been tried with contradictory results, but a recent study suggests that combined therapy with corticosteroids and azathioprine may be beneficial.

- Although the term “Henoch–Schönlein purpura” was originally used to designate a syndrome that can be characterized by many different types of small-vessel vasculitis (i.e., combinations of purpura, abdominal pain, and nephritis), the use of the term should now be restricted to the specific clinicopathological entity caused by vascular IgA-dominant immune complexes. The misuse of this term for patients with ANCA-associated small-vessel vasculitis who present with purpura, abdominal pain, and nephritis is particularly problematic because these patients do not have a good prognosis and should be treated quickly with immunosuppressive therapy, as will be discussed later in this review.

Cryoglobulinemic Vasculitis

Cryoglobulinemic vasculitis is caused by the localization of mixed cryoglobulins in vessel walls, which incites acute inflammation. Venules, capillaries, and arterioles are preferentially involved.

- Patients with this disease have an average age of approximately 50 years. The most frequent manifestations are purpura, arthralgias, and nephritis. Mixed cryoglobulins and rheumatoid-factor activity are typically detectable in serum. Most patients have an associated infection with hepatitis C virus, which is thought to be etiologic. A very distinctive and diagnostically useful complement abnormality is the presence of very low levels of early components (especially C4) with normal or slightly low C3 levels. As with Henoch–Schönlein purpura, the main cause of morbidity is progressive glomerulonephritis, which most often has a type I membranoproliferative phenotype.

- Mild disease, such as slight purpura and arthralgias, usually is adequately treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs alone. Serious visceral involvement, such as in glomerulonephritis, usually requires treatment with corticosteroids combined with a cytotoxic drug (e.g., cyclophosphamide), which improves the outcome of glomerulonephritis and also ameliorates purpura, arthralgias, and other vasculitic symptoms. Plasmapheresis has been used, but its value is unproven. Recently, interferon alfa has been touted as a beneficial adjuvant in patients with cryoglobulinemic vasculitis associated with hepatitis C virus infection, but larger controlled trials are required before the value of this approach can be conclusively determined.

Anca-Associated Small-Vessel Vasculitis

- ANCA-associated small-vessel vasculitis is the most common primary systemic small-vessel vasculitis in adults and includes three major categories: Wegener’s granulomatosis, microscopic polyangiitis, and Churg–Strauss syndrome. These histologically identical small-vessel vasculitides preferentially involve venules, capillaries, and arterioles, and may also involve arteries and veins Wegener’s granulomatosis is differentiated from the other two by the presence of necrotizing granulomatous inflammation in the absence of asthma; Churg–Strauss syndrome is differentiated by the presence of asthma, eosinophilia, and necrotizing granulomatous inflammation; and microscopic polyangiitis is differentiated by the absence of granulomatous inflammation and asthma. Rapid diagnosis of ANCA-associated small-vessel vasculitis is critically important because life-threatening injury to organs often develops quickly and is mitigated dramatically by immunosuppressive treatment.

- ANCA-associated small-vessel vasculitis affects people of all ages but is most common in older adults in their 50s and 60s, and it affects men and women equally. In the United States, the disease is more frequent among whites than blacks. Its incidence is approximately 2 in 100,000 people in the United Kingdom and approximately 1 in 100,000 in Sweden. Although Wegener’s granulomatosis, microscopic polyangiitis, and Churg–Strauss syndrome are categorized as ANCA-associated small-vessel vasculitis, it is important to realize that a minority of patients with typical clinical and pathological features of these diseases are ANCA-negative.

Wegener’s granulomatosis

- Over 90 percent of patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis have upper or lower respiratory tract disease or both. Manifestations of upper respiratory tract disease include sinus pain, purulent sinus drainage, nasal mucosal ulceration with epistaxis, and otitis media. More serious complications include necrosis of the nasal septum with perforation or saddle-nose deformation and injury to the facial nerve by otitis media resulting in facial paralysis. Tracheal inflammation and sclerosis, often in the subglottic region, cause stridor and may lead to dangerous airway stenosis, which occurs in approximately 15 percent of adults and almost 50 percent of children with this disease. A minority of patients initially have indolent or aggressive upper respiratory tract disease alone, but most also have pulmonary disease.

- Necrotizing granulomatous pulmonary inflammation produces nodular radiographic densities, whereas alveolar capillaritis causes pulmonary hemorrhage with less fixed and more irregular infiltrates. Massive pulmonary hemorrhage caused by capillaritis is the most life-threatening manifestation of ANCA-associated small-vessel vasculitis and warrants rapid institution of aggressive immunosuppressive therapy.

- Approximately 80 percent of patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis will go on to have glomerulonephritis, although less than 20 percent have nephritis at the time of presentation. The glomerulonephritis is characterized by focal necrosis, crescent formation, and the absence or paucity of immunoglobulin deposits. An identical pauci-immune necrotizing and crescentic glomerulonephritis occurs in patients with microscopic polyangiitis and Churg–Strauss syndrome, and also occurs as a disease limited to the kidneys. Other manifestations of the disease include ocular inflammation, cutaneous purpura and nodules, peripheral neuropathy, arthritis, and diverse abdominal visceral involvement.

- The classic triad of respiratory tract granulomatous inflammation, systemic small-vessel vasculitis, and necrotizing glomerulonephritis readily suggests the diagnosis, but atypical presentations, such as isolated subglottic stenosis or orbital pseudotumor, may not. In patients with the latter presentation, a positive ANCA test is helpful for substantiating a diagnosis of Wegener’s granulomatosis.

- Treatment of aggressive Wegener’s granulomatosis, as well as of microscopic polyangiitis, has three phases: induction of remission, maintenance of remission, and treatment of relapse. After the seminal observations of Novack and Pearson, Fauci and his associates documented the value of cyclophosphamide in the treatment of Wegener’s granulomatosis. Current induction therapy often uses cyclophosphamide combined with corticosteroids. Corticosteroids alone may be adequate for ameliorating indolent limited disease but are inadequate for patients with the generalized disease.

- In patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis or microscopic polyangiitis who have aggressive diseases, such as acute nephritis or pulmonary hemorrhage, we recommend induction with intravenous methylprednisolone at a dose of 7 mg per kilogram of body weight per day for three days, followed by tapering doses of prednisone. This treatment is combined with oral cyclophosphamide at 2 mg per kilogram per day, or intravenous cyclophosphamide at 0.5 g per square meter of body-surface area per month, adjusted upward to 1 g per square meter on the basis of the patient’s leukocyte count. Combined therapy with corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide induces improvement in over 90 percent of patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis and complete remission in 75 percent. A common strategy is to discontinue corticosteroids after remission is achieved, usually within 3 to 5 months, and to continue cyclophosphamide for 6 to 12 months. An alternative strategy for maintaining remission is a conversion from cyclophosphamide to azathioprine once remission is achieved. Approximately 50 percent of patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis have at least one relapse within five years. The best treatment for reversing relapses is controversial but usually involves reinstituting treatment similar to the induction regimen.

- Both corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide predispose patients to life-threatening infections, and cyclophosphamide causes hemorrhagic cystitis, ovarian and testicular failure, and cancer. For example, Talar-Williams et al. have estimated the incidence of bladder cancer after the first exposure to cyclophosphamide to be 5 percent 10 years after treatment and 16 percent after 15 years. The risks and benefits of aggressive immunosuppression must be assessed in each patient, and the treatment tailored accordingly. There should be vigilance for and prompt treatment of complications arising from treatment.

- Less-toxic therapy may be sufficient in patients with localized or mild Wegener’s granulomatosis. For example, Sneller et al. achieved remission with low-dose methotrexate plus prednisone in 71 percent of patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis that was “not immediately life-threatening.” Methotrexate also may be useful for maintenance of remission. Treatment with methotrexate is limited in patients with renal disease because of increased toxicity.

Because relapses are associated with respiratory tract infections and with chronic nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus, the antimicrobial agent trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole has been evaluated for maintenance of remission, with mixed results. Stegeman et al. concluded that it is useful for maintaining remission, but de Groot et al. did not agree.

Microscopic polyangiitis

- Microscopic polyangiitis is characterized by pauses-immune necrotizing small-vessel vasculitis without clinical or pathological evidence of necrotizing granulomatous inflammation. Over 80 percent of patients with microscopic polyangiitis have ANCA, most often perinuclear ANCA (MPO-ANCA). This helps distinguish microscopic polyangiitis from ANCA-negative small-vessel vasculitis but does not distinguish microscopic polyangiitis from other types of disease associated with ANCA. Positive ANCA and negative serologic tests for hepatitis B help differentiate microscopic polyangiitis from polyarteritis nodosa.

- Pathologically, microscopic polyangiitis may cause necrotizing arteritis that is histologically identical to that caused by polyarteritis nodosa. By the approach advocated by the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference polyarteritis nodosa and microscopic polyangiitis are distinguished pathologically by the absence of vasculitis in vessels other than arteries in polyarteritis nodosa and the presence of vasculitis in vessels smaller than arteries (i.e., arterioles, venules, and capillaries) in microscopic polyangiitis. According to this definition, the presence of dermal leukocytoclastic venulitis, glomerulonephritis, pulmonary alveolar capillaritis, or vasculitis in any vessel smaller than an artery would exclude a diagnosis of polyarteritis nodosa and indicate some form of small-vessel vasculitis. On the other hand, identification of necrotizing arteritis in a skeletal-muscle biopsy or peripheral-nerve biopsy, for example, indicates some form of necrotizing vasculitis but is not diagnostic of polyarteritis nodosa, because many other necrotizing vasculitides, such as microscopic polyangiitis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and Churg–Strauss syndrome, can also affect arteries

- Microscopic polyangiitis has the same spectrum of manifestations of small-vessel vasculitis as Wegener’s granulomatosis but does not include granulomatous inflammation. Approximately 90 percent of patients have glomerulonephritis, which is accompanied by a variety of other organ involvements. Microscopic polyangiitis is the most common cause of the pulmonary–renal syndrome.

- Microscopic polyangiitis that is causing major organ damage is treated with a combination of corticosteroids and cytotoxic agents. Our treatment approach is the same as that for aggressive Wegener’s granulomatosis, which was described earlier in this review, and uses intravenous methylprednisolone followed by prednisone combined with intravenous or oral cyclophosphamide. Alveolar capillaritis with pulmonary hemorrhage is the most life-threatening complication and should be treated promptly with combined therapy, and possibly with plasmapheresis. The glomerulonephritis is usually rapidly progressive if not promptly and appropriately treated with a combination of high-dose corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide, which induces remission in approximately 80 percent of patients. The greatest risk factor for a poor renal outcome is a delay in treatment until renal insufficiency has developed. Relapse occurs in about a third of patients within two years. Approximately two-thirds of patients who relapse respond to an immunosuppressive regimen similar to the induction therapy.

Because the treatment of microscopic polyangiitis and Wegener’s granulomatosis is essentially the same when there is major organ injury, it is not necessary to distinguish conclusively between these closely related variants of ANCA-associated small-vessel vasculitis before starting treatment. For example, an ANCA-positive patient with pulmonary infiltrates, hemoptysis, and pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis on renal biopsy may have either microscopic polyangiitis or Wegener’s granulomatosis. Resolving this differential diagnosis should not delay the start of induction therapy with combined corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide.

Churg–Strauss syndrome

- Churg–Strauss syndrome has three phases: allergic rhinitis and asthma; eosinophilic infiltrative disease, such as eosinophilic pneumonia or gastroenteritis; and systemic small-vessel vasculitis with granulomatous inflammation. The vasculitic phase usually develops within three years of the onset of asthma, although it may be delayed for several decades. Approximately 70 percent of patients with this disease have ANCA, usually perinuclear ANCA (MPO-ANCA). Virtually all patients have eosinophilia (more than 10 percent eosinophils in the blood).

References