Bilateral Neural Foraminal Stenosis at T11 Vertebra/Bilateral Neural Foraminal Stenosis is compressed on both sides due to narrowing of the foramen that may be caused by an enlarged joint, a collapsed disc space, or a foraminal herniated disc.

Foraminal stenosis is the narrowing or tightening of the openings between the bones in your spine. These small openings are called the foramen. Foraminal stenosis is a specific type of spinal stenosis. Neural foraminal stenosis, or neural foraminal narrowing, is a type of spinal stenosis. It occurs when the small openings between the bones in your spine, called the neural foramina, narrow or tighten. The nerve roots that exit the spinal column through the neural foramina may become compressed, leading to pain, numbness, or weakness.

Nerves pass through the foramen from your spinal cord out to the rest of your body. When the foramen close in, the nerve roots passing through them can be pinched. A pinched nerve can lead to radiculopathy — or pain, numbness, and weakness in the part of the body the nerve serves.

Lumbar foraminal neuropathy is a pathologic condition of neurovascular contents in the foramen causing radicular symptoms, which is associated with narrowed foramen. Foraminal stenosis is common in the elderly population [rx], characterized by narrowing of the bony exit of the nerve root due to degenerative changes in the intervertebral discs, zygapophyseal joint, ligaments, and bony parts. The narrowed foramen causes irritation and compression of the entrapped nerve to develop inflammation and pain, as well as vascular congestion causing neurogenic claudication. Depending on the magnitude of neuroforaminal narrowing and the impact on the neurovascular contents, symptoms may vary from pain, tingling, and numbness to motor weakness and gait impairment.

Anatomy

The lumbar foramen is formed by the vertebral body, pedicles, disc, superior and inferior articular processes, ligamentum flavum, and zygapophyseal joint. A foramen is an inter-pedicular osseous hole appearing with an oval or inverted teardrop shape that has three anatomical zones, the entrance ( internal), mid ( intraformational), and exit (extraforaminal) zones.

Superoposterior view of the foramen. Internal (green), intraformational (red), and external (blue) zones.

A bilateral neural foraminal stenosisis segmented into multiple subcompartments and stabilized by transforaminal ligaments, through which the nerve root, dorsal root ganglion (DRG), radicular artery, and veins, and lymphatics pass. Nerve roots and the DRG exit the dural sac and course through the lateral recess to the superior and anterior region of the foramen. The 5th lumbar nerve root occupies 25%–30% of the bilateral neural foraminal stenosis is space, while the other lumbar nerve roots occupy 7%–22% of the foramen [rx].

There are two types of foraminal ligaments; radiating ligaments that connect the nerve root sleeves to the wall of the foramen and transverse processes, and transforaminal ligaments [rx,rx]. The ligaments in the internal zone are seen in the inferior aspect of the medial portion of the foramen, and bilateral neural foraminal stenosis creating sub-compartments in the lower foramen where veins run through. Transforaminal ligaments in the extraforaminal zone are seen in the anterior, anterior-superior, and horizontal-mid portions. The external ligaments are divided into the superior, middle, and inferior corporotransverse ligaments attaching to the transverse process. The ligaments are fascial condensations with ligamentous features and are not always present at all levels or on both sides of the spine. The overall incidence of the transforaminal ligaments is approximately 47%, and the ligaments occupy as much as 30% of the foramen [rx].

The lateral view of foramen with ligaments, nerve root (NR), and dorsal root ganglion (DRG).

The mid-zone is a foraminal region where the nerve root and DRG pass. The lumbar DRG, lacking a protective capsule, is commonly located in the intraformational area. Moon et al. [rx] found that at the 4th lumbar spine the DRG was 48% intraforaminal, 41% intraspinal, and 6% extraforaminal. In the 5th lumbar spine, the DRG positions were 75% intraforaminal, 10% intraspinal, and 6% extraforaminal.

Types of Bilateral Neural Foraminal Stenosis

Symptoms of bilateral neural foraminal stenosis are due to foraminal stenosis vary depending on which part of your spine is affected.

- Cervical stenosis – develops when the foramen of your neck narrows. Pinched nerves in your neck can cause a sharp or burning pain that starts in the neck and travels down your shoulder and arm. Your arm and hand may feel weak and numb with “pins and needles sensation in bilateral neural foraminal stenosis.

- Thoracic stenosis – develops when the foramen in the upper portion of your back narrows. Pinched nerve roots in this part of your back can cause pain and numbness that wrap around the front of your body. This is the least common area to be affected by bilateral neural foraminal stenosis.

- Lumbar stenosis – develops when the foramen of your low back narrows. The lower back is the section of your spine most likely to be affected by foraminal stenosis. This can be felt as pain, tingling, numbness, and weakness in the buttock, leg, and sometimes the foot. Sciatica is a term you may have heard for this type of pain.

Causes of Bilateral Neural Foraminal Stenosis at T11 Vertebra

- Spinal injuries – Car accidents and other trauma can cause dislocations or fractures of one or more vertebrae. Displaced bone from a spinal fracture may damage the contents of the bilateral neural foraminal stenosis. Swelling of nearby tissue immediately after back surgery also can put pressure on the spinal cord or nerves.

- Degenerative disk – A degenerative disk is where a vertebral disc degenerates and slips out of place putting pressure on the exiting nerve. It is most common in the lumbar spine, but can also happen in the thoracic or the cervical spine in bilateral neural foraminal stenosis.

- Herniated disk – Also known as a slipped or prolapsed disk, a herniated disk means one of the discs of cartilage that sits between the vertebrae is damaged. The soft cushions that act as shock absorbers between your vertebrae tend to dry out with age. Cracks in a disk’s exterior may allow some of the soft inner material to escape and press on the spinal cord or nerves in bilateral neural foraminal stenosis.

- Spondylolisthesis – Spondylolisthesis is where one vertebra slides in front or back of the vertebra below it. It commonly occurs in the lumbar spine but can occur elsewhere in the spine. This can cause narrowing of bilateral neural foraminal stenosis of the exiting nerve in the foramen.

- Overgrowth of bone – Wear and tear damage from osteoarthritis on your spinal bones can prompt the formation of bone spurs, which can grow into the spinal canal. Paget’s disease, a bone disease that usually affects adults, also can cause bone overgrowth in the spine.

- Thickened ligaments – The tough cords that help hold the bones of your spine together can become stiff and thickened over time. These thickened ligaments can bulge into the bilateral neural foraminal stenosis.

- Rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis – Arthritis develops when cartilage breaks down, and this can also happen to the discs of cartilage that sit between the vertebrae of bilateral neural foraminal stenosis

- Osteophyte – This is a bone spur growth in the back quite common in those aged over 60 and usually caused by osteoarthritis.

- Trauma – Repetitive trauma to the spine damages the vertebrae and causes them to slip. This is more common in athletes such as gymnasts and weightlifters. A sudden injury can also make a disc slip.

- Tumors. Abnormal growths can form inside the spinal cord, within the membranes that cover the spinal cord, or in the space between the spinal cord and vertebrae. These are uncommon and identifiable on spine imaging with an MRI or CT.

| Extraforaminal etiology: bilateral neural foraminal stenosis |

| Congenital |

| Idiopathic |

| Achondroplasia |

| Spinal dysraphism |

| Segmentation failure |

| Osteopetrosis |

| Developmental |

| Early vertebral arch ossification |

| Shortened pedicles |

| Thoracolumbar kyphosis |

| Apical vertebral wedging |

| Morquio syndrome |

| Osseous exostosis |

| Acquired |

| Disc disorders with bulging or herniation |

| Degenerative disc disease |

| Osteoarthritis |

| Spondylolisthesis |

| Scoliosis |

| Hypertrophy of ligamentum flavum |

| Pedicular hypertrophy |

| Facet arthritis and hypertrophy |

| Facet joint cyst |

| Osteophytes |

| Compression fracture |

| Paget’s disease |

| Ankylosing spondylitis |

| Post-traumatic |

| Post-surgery |

| Neoplasm |

| Intraforaminal etiology |

| Fibrosis |

| Epidural/foraminal inflammation |

| Degenerative spinal disorders |

| Post-surgery |

| Transforaminal ligament |

| Hypertrophy |

| Calcification/ossification |

Symptoms of Bilateral Neural Foraminal Stenosis at T11 Vertebra

Symptoms vary depending on the location of the bilateral neural foraminal stenosis and which nerves are affected.

In the neck (cervical spine)

- Your pain may worsen with certain activities, like bending, twisting, reaching, coughing, or sneezing.

- Numbness or tingling in a hand, arm, foot, or leg

- Weakness in a hand, arm, foot, or leg

- Problems with walking and balance in case of bilateral neural foraminal stenosis

- Neck pain, Paresthesia, itching, tingling, numbness

- In severe cases, bowel or bladder dysfunction (urinary urgency and incontinence)

- Pain that develops over the course of time (often years)

- Muscle weakness, tingling, and numbness

- Pins and needles sensation in bilateral neural foraminal stenosis

- Burning pain in the extremities

In the lower back (lumbar spine)

- Numbness or tingling in a foot or leg

- Weakness in a foot or leg

- Pain or cramping in one or both legs when you stand for long periods of time or when you walk, which usually eases when you bend forward or sit

- Back pain is most common in bilateral neural foraminal stenosis

- Sciatic pain from nerve root pressure or inflammation

- Tingling, numbness, and/or weakness in arms/legs

- Loss of reflexes or balance

Overall

- Neurogenic claudication refers to leg symptoms encompassing the buttock, groin, and anterior thigh, as well as radiation down the posterior part of the leg to the feet. In addition to pain, leg symptoms can include fatigue, heaviness, weakness, and/or paresthesia in bilateral neural foraminal stenosis.

- Your pain may worsen with certain activities, like bending, twisting, reaching, coughing, or sneezing.

- Patients with LSS also can report nocturnal leg cramps(rx) and neurogenic bladder symptoms.(rx)

- Symptoms of spinal stenosis narrowing of the spinal canal, generally as a result of spinal nerve root involvement within the lumbar spinal canal, may include general discomfort, weakness in the legs, numbness, or paresthesias.

- A key feature of neurogenic claudication is its relationship to the patient’s posture where lumbar extension increases, and flexion decreases pain, thereby attributing a specific “simian stance” seen among these subsets of patients.

- The same phenomenon is accountable for better tolerance to climbing uphill compared to downhill walking.[rx] Pain is exacerbated by walking, standing, or upright exercises.

- Pain relief occurs with sitting or forward flexion at the waist such as involved with squatting, leaning forward, or lying down. Many patients are asymptomatic when inactive.

- Extending the back while standing leading to the development of symptoms which promptly resolve by subsequently leaning forward 20 to 40 degrees at the waist a classic presentation.

Diagnosis of Bilateral Neural Foraminal Stenosis at T11 Vertebra

The diagnosis in bilateral neural foraminal stenosis is following

- History in these patients should include the chief complaint, onset of symptoms, alleviating and aggravating factors, radicular symptoms, and any past treatments history and previous treatment history, or surgery. The most common subjective complaints are axial lumbar pain and ipsilateral arm pain or bilateral neural foraminal stenosis, paresthesias in the associated dermatomal distribution pain.

Self-administered, self-reported history questionnaire to and its clinical subtypes

| Q1 | Numbness and/or pain in the thighs down to the calves and shins. |

| Q2 | Numbness and/or pain increase in intensity after walking for a while, but are relieved by taking a rest. |

| Q3 | Standing for a while brings on numbness and/or pain in the thighs down to the calves and shins. |

| Q4 | Numbness and/or pain are reduced by bending forward. |

| Key questions for diagnosis of cauda equina symptoms: | |

| Q5 | Numbness is present in both legs. |

| Q6 | Numbness is present in the soles of both feet |

| Q7 | Numbness arises around the buttocks. |

| Q8 | Numbness is present, but the pain is absent. |

| Q) | A burning sensation arises around the buttocks. |

| Q10 | Walking nearly causes urination. |

Physical Examination

A careful neurological examination can help in localizing the level of the compression. The sensory loss, weakness, pain location, and reflex loss associated with the different levels are described above. A thorough neurological examination is necessary to evaluate sensory disturbances, motor weakness, and deep tendon reflex abnormalities. Typical findings of solitary nerve lesion due to compression by a herniated disc with bulging, bilateral neural foraminal stenosis in the lumbar spine

- L1 Nerve – pain and sensory loss are common in the inguinal region. Hip flexion weakness is rare, and no stretch reflex is affected.

-

L2-L3-L4 Nerves – back pain radiating into the anterior thigh and medial lower leg; sensory loss to the anterior thigh and sometimes medial lower leg; hip flexion and adduction weakness, knee extension weakness; decreased patellar reflex.

-

L5 Nerve – back, radiating into buttock, lateral thigh, lateral calf and dorsum foot, great toe; sensory loss on the lateral calf, dorsum of the foot, webspace between first and second toe; weakness on hip abduction, knee flexion, foot dorsiflexion, toe extension and flexion, foot inversion and eversion; decreased semitendinosus/semimembranosus reflex.

-

S1 Nerve – back, radiating into buttock, lateral or posterior thigh, posterior calf, lateral or plantar foot; sensory loss on the posterior calf, lateral or plantar aspect of foot; weakness on hip extension, knee flexion, plantar flexion of the foot; Achilles tendon; Medial buttock, perineal, and perianal region; weakness may be minimal, with urinary and fecal incontinence as well as sexual dysfunction.

-

S2-S4 Nerves – sacral or buttock pain radiating into the posterior aspect of the leg or the perineum; sensory deficit on the medial buttock, perineal, and perianal region; absent bulbocavernosus, anal wink reflex.

A physical exam for diagnosing bilateral neural foraminal stenosis may include one or more of the following tests

- Palpation – Palpating (feeling by hand) certain structures can help identify the pain source. For example, worsened pain when pressure is applied to the spine may indicate sensitivity caused by a damaged disc, bilateral neural foraminal stenosis.

- Movement tests – Tests that assess the spine’s range of motion may include bending the neck or torso forward, backward, or to the side. Additionally, if raising one leg in front of the body worsens leg pain, it can indicate a lumbar herniated disc (straight leg raise test).

- Muscle strength – A neurological exam may be conducted to assess muscle strength and determine if a nerve root is compressed by a herniated disc. A muscle strength test may include holding the arms or legs out to the side or front of the body to check for tremors, muscle atrophy, bilateral neural foraminal stenosis, or other abnormal movements.

- Reflex test – Nerve root irritation can dampen reflexes in the arms or legs. A reflex test involves tapping specific areas with a reflex hammer. If there is little or no reaction, it may indicate a compressed nerve root in the spine.

Lab Test

- A medical history – in which you answer questions about your health, symptoms, and activity.

- A physical exam to assess your strength – reflexes, sensation, stability, alignment, and motion. You may also need blood tests.

- Laboratory testing – may include white blood cell (WBC) count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein (CRP).

- Elevated ESR – could indicate infection, malignancy, chronic disease, inflammation, trauma, or tissue ischemia.

- Elevated CRP – levels are associated with infection.

Imaging

- X-rays – view the bony vertebrae in your spine and can tell your doctor if any of them are too close together or whether you have arthritic changes, bone spurs, or fractures narrowing of the spinal canal. It’s not possible to diagnose a herniated disc with paracentral disc herniation, bilateral neural foraminal stenosis in this test alone.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scan – is a noninvasive test that uses a magnetic field and radiofrequency waves to give a detailed view of the soft tissues of your spine with a bulging disc and paracentral disc herniation, bilateral neural foraminal stenosis. Unlike an X-ray, nerves and discs are clearly visible. It may or may not be performed with a dye (contrast agent) injected into your bloodstream. An MRI can detect which disc is damaged and if there is any nerve compression. It can also detect bony overgrowth, spinal cord tumors, abscesses, or narrowing of the spinal canal, bilateral neural foraminal stenosis.

- A myelogram – is a specialized X-ray where dye is injected into the spinal canal through a spinal tap. An X-ray fluoroscope then records the images formed by the dye. The dye used in a myelogram shows up white on the X-ray, allowing the doctor to view the spinal cord and canal, a bulging disc, bilateral neural foraminal stenosis paracentral disc herniation, in detail. Myelograms can show a nerve being pinched and a bulging disc by a herniated disc, bony overgrowth, narrowing of the spinal can spinal cord tumors, and abscesses.

- Computed Tomography (CT) scan – is a noninvasive test that uses an X-ray beam and a computer to make 2-dimensional images of your spine. It may or may not be performed with a dye (contrast agent) injected into your bloodstream. This test is especially useful for confirming which bulging disc and narrowing of the spinal canals or bilateral neural foraminal stenosis disc are damaged.

- Electromyography (EMG) & Nerve Conduction Studies (NCS) – EMG tests measure the electrical activity of your muscles. Small needles are placed in your muscles, and the results are recorded on a special machine. NCS is similar, but it measures how well your nerves pass an electrical signal from one end of the nerve to another. These tests can detect nerve damage and muscle weakness and a bulging disc, paracentral disc herniation, bilateral neural foraminal stenosis.

- Discogram – A discogram may be recommended to confirm which bulging disc is painful if surgical treatment is considered. In this test, the radiographic dye is injected into the disc to recreate disc pain from the dye’s added pressure. Electrodiagnostic evidence of fibrillation potentials and the absence of a tibial H-wave may aid in further confirming the diagnosis of lumbar canal stenosis.[rx]

- Doppler ultrasound – is a noninvasive test that uses reflected sound waves to evaluate blood as it flows through a blood vessel. This test may be performed to rule out peripheral artery disease as a cause of painful leg symptoms.

Treatment Of Bilateral Neural Foraminal Stenosis at T11 Vertebra

Non-Surgical

- Spine-Specialized physical therapy – typically includes a combination of stretching, strengthening, and aerobic exercise to provide better stability and support for the spine.

- Massage therapy – can help reduce muscle tension and muscle spasms, which may add to back or neck pain. Muscle tension is especially common around an unstable spinal segment where a disc is unable to provide the necessary support.

- Ice & Moist Heat Application – Ice application where the ice is wrapped in a towel or an ice pack for about 20 minutes to the affected region, thrice a day, helps in relieving the symptoms of a disc bulge. Heat application in the later stages of treatment also provides the same benefit.

- Hot Bath – Taking a hot bath or shower also helps in dulling the pain from a disc bulge, and bilateral neural foraminal stenosis. Epsom salts or essential oils can be added to a hot bath. They will help in soothing the inflamed region.

- Chiropractic – Spinal adjustment is a treatment that applies pressure to an area to align the bones and return joints to more normal motion. Good motion helps reduce pain, muscle spasms or tightness, and improves nervous system function and overall health. The motion also reduces the formation of scar tissue, which can lead to stiffness.

- Holistic therapies – Some patients find acupuncture, acupressure, yoga, nutrition/diet changes, meditation, and biofeedback helpful in managing pain as well as improving overall health.

-

Collar Immobilization – In patients with acute neck pain, a short course (approximately one week) of collar immobilization may be beneficial during the acute inflammatory period.

-

Traction – This May be beneficial in reducing the radicular symptoms associated with disc herniations. Traction is the best essential treatment for bulging discs, narrowing of the spinal canal, bilateral neural foraminal stenosis, pinched nerves, radiating pain management. It can be done in a manual and dynamic way to relieves pain in bulging discs. Theoretically, traction would widen the neuroforamen and relieve the stress placed on the affected nerve, which, in turn, would result in the improvement of symptoms. This therapy involves placing approximately 8 to 12 lbs of traction at an angle of approximately 24 degrees of neck flexion over a period of 15 to 20 minutes.

- Massage therapy – may give short-term pain relief, but not functional improvement, for those with acute lower back pain. It may also give short-term pain relief and functional improvement for those with long-term (chronic) and sub-acute lower back pain, but this benefit does not appear to be sustained after 6 months of treatment. There does not appear to be any serious adverse effects associated with massage.

- Acupuncture – may provide some relief for back pain. However, further research with stronger evidence needs to be done.

- Spinal manipulation – is a widely-used method of treating back pain, although there is no evidence of long-term benefits. Complications from manipulation are rare and can include worsening radiculopathy, myelopathy, spinal cord injury, and vertebral artery injury. These complications occur ranging from 5 to 10 per 10 million manipulations.

- Back school – is an intervention that consists of both education and physical exercises. A 2016 Cochrane review found the evidence concerning back school to be very low quality and was not able to make generalizations as to whether the back school is effective or not.

- Patient education – on proper body mechanics (to help decrease the chance of worsening pain or damage to the disk)

- Physical therapy – which may include ultrasound, massage, conditioning, and exercise. The goal of physical therapy is to help you return to full activity as soon as possible and prevent re-injury. Physical therapists can instruct you on proper posture, lifting, and walking techniques, and they’ll work with you to strengthen your lower back, leg, and stomach muscles. They’ll also encourage you to stretch and increase the flexibility of your spine and legs. Exercise and strengthening exercises are key elements to your treatment and should become part of your life-long fitness. Physiotherapy is an accepted treatment for LSS. Physiotherapy related treatments include, but are not limited to:

-

Exercise (aerobic, strength, flexibility)

-

Specific exercises in lumbar flexion (cycling)

-

Bodyweight supported treadmill walking

-

Muscle coordination training

-

Balance training

-

Lumbar semi-rigid orthosis

-

Braces and corsets

-

Pain-relieving treatments (heat, ice, electrical stimulation, massage, ultrasound)

-

Spinal manipulation

-

Postural instruction.

-

One study found that treatments most commonly used by patients are massage (27%), strengthening exercises (23%), flexibility exercises (18%), and heat or ice (14%), whereas physiotherapists most often advocate flexibility exercises (87%), stabilization exercises (86%), strengthening exercises (83%), heat or ice (76%), acupuncture (63%), and joint mobilization (62%).[rx]

- Over the Door Traction – This is a very effective treatment for a disc bulge. It helps in relieving muscle spasms and pain. Typically a 5 to 10-pound weight is used and it is important that patients do this under medical guidance.

- Weight control – By keto diet or maintaining or changing the food habit to reduce the weight not any movement during the time of acute pain.

- Use of lumbosacral back support – Generally, back braces are categorized as flexible, semi-rigid, and rigid. Rigid braces tend to be used for moderate to severe cases of pain and/or instability, such as to assist healing of spinal fractures or after back surgery. Semi-rigid and flexible braces are used for more mild or moderate pain.

- Eat Nutritiously During Your Recovery – All bones and tissues in the body need certain nutrients in order to heal properly and in a timely manner. Eating a nutritious and balanced diet that includes lots of minerals and vitamins is proven to help heal back pain of all types of lumbar disc disease. Therefore focus on eating lots of fresh produce (fruits and veggies), whole grains, lean meats, and fish to give your body the building blocks needed to properly healing PLID, and narrowing of the spinal canal. In addition, drink plenty of purified water, milk, and other dairy-based beverages to augment what you eat.

- In bulging disc needs ample minerals (calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, boron) and protein to become strong and healthy again.

- Excellent sources of minerals/protein include dairy products, tofu, beans, broccoli, nuts and seeds, sardines, and salmon.

- Important vitamins that are needed for bone healing include vitamin C (needed to make collagen), vitamin D (crucial for mineral absorption), and vitamin K (binds calcium to bones and triggers collagen formation).

- Conversely, don’t consume food or drink that is known to impair bone/tissue healing, such as alcoholic beverages, sodas, most fast food items, and foods made with lots of refined sugars and preservatives.

Medications

The medication for bilateral neural foraminal stenosis

- Analgesics – Such as paracetamol and prescription-strength drugs that relieve pain but not inflammation.

- Muscle Relaxants – These medications provide relief from spinal muscle spasms. Muscle relaxants, such as baclofen, tolperisone, eperisone, methocarbamol, carisoprodol, and cyclobenzaprine, may be prescribed to control muscle spasms.

- Neuropathic Agents – Drugs(pregabalin & gabapentin) that address neuropathic—or nerve-related—pain. This includes burning, numbness, and tingling.

- Opioids – Also known as narcotics, these medications are intense pain relievers that should only be used under a doctor’s careful supervision.

- NSAIDs – Prescription-strength drugs that reduce both pain and inflammation. Pain medicines and anti-inflammatory drugs help to relieve pain and stiffness, allowing for increased mobility and exercise. There are many common over-the-counter medicines called non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). They include mainly or first choice etodolac, then aceclofenac, etoricoxib, ibuprofen, and naproxen.

- Calcium & vitamin D3 – To improve bone health and healing fracture. As a general rule, men and women age 50 and older should consume 1,200 milligrams of calcium a day, and 600 international units of vitamin D a day.

- Glucosamine & Diacerein, Chondroitin sulfate – can be used to tightening the loose tendon, cartilage, ligament, and cartilage, ligament regenerates cartilage or inhabits the further degeneration of cartilage, ligament.

- Dietary supplement – to remove general weakness & improved health.

- Vitamin B1, B6, and B12 – It is essential for neuropathic pain management, pernicious anemia, with vitamin b complex deficiency pain, paresthesia, numbness, itching with diabetic neuropathy pain, myalgia, etc.

- Antidepressants – A drug that blocks pain messages from your brain and boosts the effects of endorphins (your body’s natural painkillers).

- Oral Corticosteroid – to healing the nerve inflammation and clotted blood in the joints. Steroids may be prescribed to reduce the swelling and inflammation of the nerves. They are taken orally (as a Medrol dose pack) in a tapering dosage over a five-day period. It has the advantage of providing almost immediate pain relief within a 24-hour period.

- Topical Medications – These prescription-strength creams, gels, ointments, patches, and sprays help relieve pain and inflammation throughout the skin.

- Steroid injections The procedure is performed under x-ray fluoroscopy and involves an injection of corticosteroids and a numbing agent into the epidural space of the spine. The medicine is delivered next to the painful area to reduce the swelling and inflammation of the nerves. About 50% of patients will notice relief after an epidural injection, although the results tend to be temporary. Repeat injections may be given to achieve the full effect. Duration of pain relief varies, lasting for weeks or years. Injections are done in conjunction with physical therapy and/or a home exercise program.

- epidural steroid injection. A steroid solution is injected into the epidural space (outer layer of the spinal canal) to reduce inflammation. This injection is by far the most common one used for herniated discs.

- Selective nerve root injection. A steroid solution and anesthetic is injected near the spinal nerve as it exits through the intervertebral foramen. This injection is also used to help diagnose which nerve root might be causing pain.

Surgery

Cervical Foraminotomy

- Cervical foraminotomy is a minimally invasive procedure for treating foraminal stenosis which involves removing a tiny piece of bone or tissue from the cervical spine that causing the compression of the nerve. When the cause of nerve compression is removed, the fissure that the nerve needs to travel through between the vertebrae is enlarged, thus reducing symptoms associated with a pinched nerve.

- Cervical foraminotomy is considered minimally invasive surgery because it requires an incision of less than one inch through the back of the neck. A tube is inserted through this incision for the removal of a small portion of the vertebra called the lamina. Highly specialized medical equipment is then used to access the compressed area for the removal of the bone or tissue.

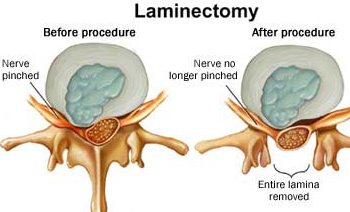

Laminotomy

In some cases, spinal conditions cause the lamina to compress the nerves, resulting in the very common symptom described as a shooting pain through the extremities. Narrowing of the spinal canal—known as spinal stenosis—is the usual cause of this pain, but this minimally invasive procedure can also treat foraminal stenosis. This procedure is similar to cervical foraminotomy except that the equipment is used to specifically remove the portion of the lamina causing the pain.

Microdiscectomy

A microdiscectomy is a non-invasive treatment that can be performed as an outpatient procedure. In many cases, patient can expect to be treated and discharged within hours, although it is certainly possible an overnight hospital stay could be required under certain conditions.

A microdiscectomy requires a small incision allowing for the removal of any matter stemming from the disc which is pressing upon the spinal cord or nerve root.

Interlaminar Stabilization

This non-invasive treatment for foraminal stenosis begins with an incision for the purpose of decompressing the affected area. This is accomplished by the extraction of that part of the spine pressing against the nerve.

Following the decompression procedure, a device called an interlaminar spacer is inserted that serves to stabilize the spine, thus reducing or eliminating the pressure which is causing the pain. This stabilizing device allows for maintenance of the decompressed area without placing any limitations upon the range of motion.

TLIF (Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion)

This technique involves inserting dilating tubes through the incision that stretch the muscle to help avoid the tearing that would otherwise be necessary to access an impacted disc. Once accessed, the disc and any proximate bone spurs are removed. The open space is then filled with a synthetic spacer to attain a more normal alignment of the spine.

Other Types of Treatment May Help to Improve

(1) Steroid injection

Transforaminal steroid injection has been most frequently used for foraminal neuropathy, owing to the direct injection of medications into the inflamed nerve root and DRG at the foramen [rx,rx]. Manchikanti et al. [rx] reported an excellent epidurographic filling of nerve roots and the ventral epidural space from transforaminal injections as compared to inconsistent filling from interlaminar injections. Nonetheless, a transforaminal injection may not achieve adequate epidurographic filling if there is significant perineural narrowing at the foramen with tissue swelling and fibrotic adhesion. So it is likely that the injection is applied during the early course of the inflammatory condition before the fibrosis is formed in order to obtain a better result. Cyteval et al. [rx] reported the predictive factor for successful pain relief was not the cause of pain, location, and pain intensity, but the duration of symptoms before the procedure. Patients with excellent results had a mean duration of symptoms of 3.04 months versus 7.96 months in the group with poor pain relief.

(2) Percutaneous adhesiolysis

The success of steroid injections depends on the spread of the injectate into the target area of the foramen, and the injections may fail if there is not enough space for the injectate to spread through, or the spread is interrupted by fibrosis with or without foraminal stenosis. There are two types of fibrosis sealing off the epidural and foraminal spaces; loose fibrous tissue like a spider web or mesh that is easy to release, and a hard, dense fibrotic band, strand, or membrane that is often difficult to release [rx,rx].

Percutaneous neuroplasty with LOA was introduced to release scar tissue for the pain of failed back surgery syndrome [rx]. A non-steerable spring-wound Racz catheter (Tun-L-KathTM; Epimed international Inc., Dallas, TX), 0.9 mm in diameter, is inserted into the region of the filling defect on epidurography and hydrostatic pressure is applied by injecting a solution to release the post-surgery scar adhesion. As the scar is detached and the epidural space is opened up, the injectate is facilitated to spread into the target area. The catheter is inserted transforaminal as well, to reach higher levels at L4 and L5, respectively [rx]. A steerable catheter, 1.3 mm in diameter, was introduced later and has been used for the purpose of neuroplasty [rx].

The neuroplasty technique has been widely used and systematic reviews show that LOA is more effective than conventional epidural injections for radicular pain from spinal stenosis and disc herniation, but not more effective than caudal epidural injections in failed back surgery syndrome [rx–rx]. LOA also shows poor outcomes for foraminal stenosis [rx].

(3) Epiduroscopy

Epiduroscopy was introduced to diagnose ongoing epidural pathology and release fibrotic adhesion [rx]. Epiduroscopy shows the epidural condition, including the location, distribution, and extent of inflammation and fibrosis, and the source of pain can be confirmed. The scope is inserted caudally with a video-guided catheter (Myelotec Inc.), 2.6 mm in diameter, and is advanced easily to the suspected target area. Adhesiolysis is performed thoroughly using a steerable catheter, and steroid medication is delivered to the inflamed nerve root precisely under direct visualization. The catheter is steered to the foraminal area and percutaneous foraminotomy at the subarticular and subpedicular areas can be achieved efficiently by manipulating the steering tip in a multi-directional way to release and break the durable fibrotic adhesion.

(4) Balloon adhesiolysis

Balloon adhesiolysis using a Fogarty catheter (Edward Lifescience, Irvine, CA), 1 mm in diameter and 5 mm with the inflated balloon, was employed to release epidural adhesions [rx]. Kim et al. [rx] applied transforaminal balloon adhesiolysis in 62 patients with foraminal stenosis. Transforaminal balloon adhesiolysis is a direct approach from outside of the foramen and foraminotomy is made with the insertion of the catheter and inflation of the balloon. It is difficult to engage the catheter when the foramen is narrowed with heavy adhesion, osteophytes, facet hypertrophy, or a hardened transforaminal ligament. Inflation of the balloon at the stenotic area may compromise circulation and compress the DRG to cause ischemia and neural damage.

A steerable catheter with a balloon tip was introduced [rx], which is inserted caudally and steered to the target foramen for balloon inflation. An epidiascope can be inserted through the lumen of the catheter as well.

(5) Percutaneous decompressive foraminotomy

Recently, percutaneous lumbar extraforaminotomy (PLEF) was presented for foraminal adhesiolysis by detaching foraminal ligaments, particularly at the posterior and inferior quadrant of the neural foramen, using a cup-shaped curette (BS extraforaminotomy kit; BioSpine Co., Seoul, Korea), 1.6 mm in diameter. PLEF mechanically releases adhesions of the inferior transforaminal ligament, the lower part of the superior corporopedicular ligament, the mid-transforaminal ligament, and part of the anterior facet joint capsule, which compress exiting nerve roots [rx]. Decompressive foraminotomy is achieved to reduce venous stasis and perineural edema, and eventually to promote the spread of injected steroid medication in the foramen.

(6) Pulsed radiofrequency (PRF)

PRF neurostimulation has emerged since it has been proven effective in the control of various chronic pain problems, especially for the control of neuropathic pain [rx]. PRF is a pulsed mode of radiofrequency consisting of short high voltage bursts at low temperatures (below 42°C). The mode of action is unclear, but references have been made to the neuromodulatory effect of the alteration of synaptic transmission of pain signals. It appears that PRF up-regulates c-fos in the DRG and modulates glial cell activation [rx,rx].

(7) Electrical stimulation

Electrical stimulation therapy has been employed for the treatment of pain from failed back surgery syndrome. Shealy et al. [rx] implanted the first spinal column stimulator (SCS) in 1967, which has been shown to effectively control the pain of neuropathic origin [rx,rx]. Its efficacy has demonstrated successful treatment in approximately 50% of patients, but concerns with paresthesia and the development of tolerance have been raised.

Shop From Rxharun..

About Us...

Editorial Board Members..

Developers Team...

Team Rxharun.

Shop From Rxharun..

About Us...

Editorial Board Members..

Developers Team...

Team Rxharun.