Anti-GBM/Anti-TBM nephritis Anti–glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) antibody disease is a rare autoimmune disorder caused by autoantibodies that attack the walls of small blood vessels (capillaries) in the kidney. Anti-GBM disease that only affects the kidneys is called anti-GBM glomerulonephritis. This is a form of inflammation (-itis), which is an injury to tissue caused by white blood cells (leukocytes). Glomerulonephritis due to Anti-GBM antibody disease is rare. It occurs in less than 1 case per million persons. It affects mostly young, white men aged 15-35. After age 50, women are more likely to be affected. The sexes overall are affected approximately at a male-female ratio of 3:2. It is seen very rarely in children. Some evidence suggests that genetics may play an important role in this disease. 60-70% of patients have both lung and kidney involvement. This is called Goodpasture’s Syndrome. 20-40% have only kidney involvement, which is called “renal limited” anti-GBM disease. Symptoms may include: chills and fever, nausea and vomiting, weight loss, chest pain, bleeding may cause anemia, respiratory failure, and kidney failure. Treatment of anti-GBM disease is focused on removing the anti-GBM antibody from the blood

Goodpasture syndrome (GPS), also known as anti-glomerular basement membrane disease, is a rare autoimmune disease in which antibodies attack the basement membrane in the lungs and kidneys, leading to bleeding from the lungs, glomerulonephritis,[rx], and kidney failure.[rx] It is thought to attack the alpha-3 subunit of type IV collagen, which has therefore been referred to as Goodpasture’s antigen.[rx] Goodpasture syndrome may quickly result in permanent lung and kidney damage, often leading to death. It is treated with medications that suppress the immune system such as corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide, and with plasmapheresis, in which the antibodies are removed from the blood.

Immune complex tubulointerstitial nephritis due to antibodies to brush border antigens of the proximal tubule has been demonstrated experimentally and rarely in humans. Our patient developed ESRD and early recurrence after transplantation. IgG and C3 deposits were conspicuous in the tubular basement membrane of proximal tubules, corresponding to deposits observed by electron microscopy. Rare subepithelial deposits were found in the glomeruli. The patient had no evidence of SLE and had normal complement levels. Serum samples from the patient reacted with the brush border of normal human kidneys, in contrast with the negative results with 20 control serum samples. Preliminary characterization of the brush border target antigen excluded megalin, CD10, and maltase. We postulate that antibodies to brush border antigens cause direct epithelial injury, accumulate in the tubular basement membrane, and elicit an interstitial inflammatory response.

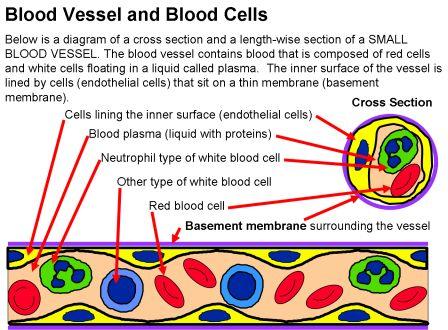

In the kidneys, the capillaries that are attacked are in the glomeruli, which filter blood and make urine. These glomerular capillaries have thin membranes in their walls that are the targets of the autoantibodies. These are called anti-glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) antibodies. The antibodies are found moving in the serum. The antibodies are connected to a very specific basement membrane protein. Injury to glomerular capillaries causes bleeding into the urine. It can also cause spillage of blood proteins into the urine, and reduced kidney function.

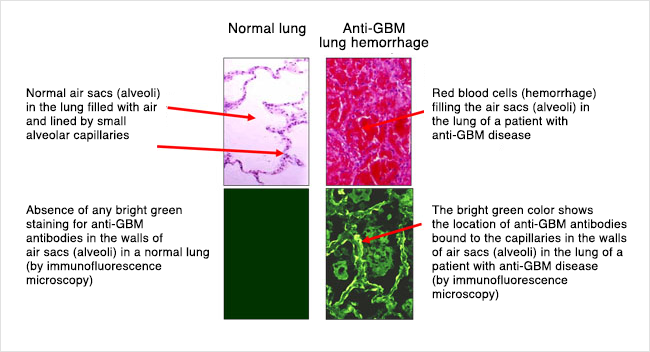

In the lungs, the capillaries that are attacked are in the thin walls of air sacs where oxygen enters the blood and carbon dioxide exits. Injury to these pulmonary capillaries causes lung bleeding and impaired breathing.

Anti-GBM disease that only affects the kidneys is called anti-GBM glomerulonephritis. This is a form of inflammation, which is injury to tissue caused by white blood cells. Anti-GBM disease that causes both kidney disease and lung disease is called Goodpasture’s syndrome. The lung disease is anti-GBM alveolar capillaritis. This is inflammation of capillaries in the air sacs of the lungs. The kidney disease is anti-GBM glomerulonephritis.

In kidney and lung capillaries, the attack by white blood cells is caused by the anti-GBM antibodies sticking to a basement membrane protein.

Under normal conditions, a layer of cells called endothelium protects the lower membrane from moving antibodies. However, at times there is increased leakiness of the cell layer. This happens in certain types of lung injury can be caused by exposures to organic solvents or hydrocarbons, smoking, infection, cocaine inhalation, and metal dusts. The lower membrane becomes more accessible to anti-GBM antibodies. This allows them to connect to the vessel wall and cause the swelling and bleeding that signals this anti-GBM disease.

How does Anti-GBM disease happen?

In anti-GBM disease, the body creates autoantibodies that recognize and attach to the basement membrane, which is part of the wall of capillary blood vessels in the kidneys and lungs.

Once the autoantibodies attach to the basement membrane, this creates a signal to the body’s immune system to attack. The immune system is designed to attack foreign invaders like infections, but in this disease, the immune system becomes targeted to the body’s own tissues. Antibodies travel in the bloodstream until they find their target or the cell that they can attach to. White blood cells (leukocytes) are infection-fighting cells in the immune system and cause inflammation and injury to the cells “marked” by the antibodies – in this disease, to the capillary blood vessels in the kidneys and/or lungs. We do not know exactly why the body starts to make these autoantibodies, though there are probably multiple things that can contribute (such as genes and environmental exposures).

In the kidneys, the autoantibodies damage capillaries (tiny blood vessels) within in the glomeruli. The glomeruli are the filters of the kidneys, which filter blood and make urine. Normally when blood goes through the capillaries in the glomeruli, water, electrolytes, and other substances are filtered from the blood into the urine, but larger things like blood cells and proteins are too big to pass through, so stay in the blood and do not pass through the filter into the urine. However, in anti-GBM disease, the glomeruli (filters) are damaged by the white blood cells and inflammation, and so protein and blood can pass into the urine. The protein and blood in the urine may not be visible but can be detected on urine tests or under the microscope. Protein in the urine can also cause the urine to look foamy. When the autoantibodies attach to the basement membrane in the glomerular capillaries, the inflammation and damage caused by the immune system can occur very quickly and causes the kidney function to decrease. Kidney function can drop very low in a short period of time – often days to a week or two. A lot of people with this disease can have severe kidney injury and damage to the point that they may require dialysis, either temporarily or long-term/permanently.

In the lungs, the capillaries (blood vessels) that are attacked and damaged by the immune system are located in the thin walls of the air sacs where oxygen enters the blood and carbon dioxide exits. Injury to these pulmonary (lung) capillaries causes bleeding into these air sacs. When blood gets into these air sacs it can make it hard to breathe. Specifically, it can cause shortness of breath and low oxygen levels. People may cough up blood as well.

Blood vessels, including capillaries, have a layer of cells called endothelial cells lining the inside of the blood vessel. These endothelial cells normally prevent antibodies in the bloodstream from coming into contact with the basement membrane (in the lungs or kidneys). However, sometimes there the endothelial cells can become leaky or having spaces between cells that expose the basement membrane underneath, allowing anti-GBN antibodies in the bloodstream to reach the basement membrane and attach. Certain types of lung injury can cause the endothelial cells to become leaky or have gaps like this – including smoking and infections, as well as exposures to other inhaled substances like organic solvents or hydrocarbons and metal dust.

The drawing below shows how anti-GBM antibodies attach to capillary walls. This picture is a cross-section of a capillary blood vessel. Gaps between the endothelial cells (yellow in this picture) allow the autoantibodies (anti-GBM antibodies) to get to the basement membrane (purple in this picture) and attach. Once the anti-GBM autoantibodies attach to the basement membrane, they attract and activate white blood cells that cause inflammation and damage the capillary walls.

Symptoms of Anti-GBM/Anti-TBM nephritis

When there is lung involvement, symptoms can include:

- Coughing up blood

- Cough (without blood)

- Shortness of breath/difficulty breathing (and even respiratory failure)

- Chest pain

When the kidneys are affected, this can cause:

- Low kidney function (kidney injury) or kidney failure, which can cause symptoms including fatigue, nausea/vomiting, poor appetite or weight loss, metallic taste in mouth, and confusion or decreased alertness. However, most people with kidney injury or damage do not have a lot of symptoms until they are in kidney failure.

- Blood in the urine – this may or may not be visible

- Foamy urine (from protein in the urine)

How is Anti-GBM diagnosed?

- A Chest X-ray or CT scan of the chest may be done to look for bleeding or infection if there are symptoms of lung problems (shortness of breath, coughing up blood)

- bronchoscopy creatinine (blood test) can be tested to evaluate kidney function

- CBC (blood test) may show anemia

- Anti-GBM antibodies can be checked (bloodwork) – this is an important part of making the diagnosis.

- Kidney biopsy (getting a small sample or piece of the kidney using a needle) can show if the kidneys are affected and make a definitive diagnosis

Immunofluorescence (IF) showed widespread granular deposits along the proximal tubular basement membrane (TBM), which stained for IgG (3+), C3 (3+), and equally for κ and λ The TBM deposits stained with IgG1 (widespread 3+), IgG2 (focal 2+), and IgG4 (widespread 3+). IgG3 was negative. The glomerular deposits were sparse, and they showed very segmental staining for IgG and did not stain for the phospholipase-A2 receptor.

Ultrastructural analysis showed widespread amorphous electron-dense deposits within the TBM, sometimes abutting the basal plasma membrane of the tubular cell. Scattered penetrating subepithelial deposits were present in a small minority of glomerular capillaries without spike formation. The GBM was diffusely but mildly thickened (harmonic mean thickness of 602 nm), indicating early diabetic glomerulopathy.

How is Anti-GBM treated?

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, treatment includes a few different parts. Anti-GBM disease can be life threatening due to bleeding in the lungs, and kidney failure can occur quickly, so starting treatment as soon as possible is important.

- If the lungs are involved, providing oxygen as needed to keep oxygen levels up. Sometimes, a breathing tube may be needed temporarily.

- If the kidneys have a lot of damage, they may not be able to function well enough to do what they need to, and dialysis may be needed to help do the kidneys’ job. This includes getting rid of fluid from the body, balancing electrolytes and acid-base levels in the blood, and removing toxins/wastes from the body.

- Plasmapheresis. This is a procedure that removes the anti-GBM antibody from the bloodstream. It can also be called plasma exchange or PLEX. A person’s blood is run through a machine that removes antibodies from the blood, then the blood is returned to the body (without the antibodies). Treatments last a couple of hours and are usually done every 1-2 days for about 2 weeks.

Immunosuppressive treatment (medicines to suppress the immune system) are given to decrease/prevent the immune system - Corticosteroids– usually this is given as a high-dose infusion of a medication called methylprednisolone (Solumedrol) daily for 3 days. Treatment with an oral (by mouth) medication such as prednisone is typically continued after the infusion and tapered off over a period of 3-9 months. This medication decreases the inflammation caused by the immune system that contributes to kidney and lung damage.

- Cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan)– this is an immune-suppressing medication that can be given as a monthly infusion or as a daily oral (by mouth) dose. This is generally continued for at least 2-3 months but up to 6 months. This medication helps to prevent the immune system from making more anti-GBM autoantibodies.

- Rituximab (Rituxan) – this is an immune-suppressing medication that is given as an IV infusion, generally in 2-4 doses spaced over 2-4 weeks. This medication has not been evaluated in trials but has been used in some patients – if cyclophosphamide is not a good option or in some patients in addition to

- Cyclophosphamide – other immunosuppressive medications such as mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine have sometimes been used in this disease after treatment with cyclophosphamide or in combination with cyclophosphamide or other immunosuppressive medications. These medications are used much less common and in selected circumstances. They should not be the primary medication used to treat the disease as cyclophosphamide is the most effective medication from the evidence we have.

- Checking levels of the anti-GBM antibody – in the blood after starting treatment is important to make sure that the antibody is being cleared from the blood and not returning. It can also help guide how long to continue treatment.

- Avoiding exposures – that could cause or trigger the disease to return is important. Although a relapse or recurrent flare is uncommon, inhalation injuries (chemical exposures, such as organic solvents) or smoking cigarettes can be a trigger to cause the disease to come back. It is extremely important not to smoke cigarettes and to avoid cigarette smoke and other inhaled chemicals if you have had this disease.

What are my chances of getting better?

Anti-GBM disease progresses very quickly in most patients who get it. One of the most important things affecting how well somebody with the anti-GBM disease does is how quickly they are treated. Since kidney disease or decreased kidney function does not cause any symptoms until the kidney function is extremely low, many people do not know they have the disease until a significant amount of injury or damage has occurred. As many as half to two-thirds of people may end up with kidney failure from the disease. The severity of kidney injury at the time of diagnosis is one of the best predictors of how someone will do, though, with treatment, some people who initially have kidney failure requiring dialysis can have improved and may not need long-term dialysis. However, because the disease does not usually relapse or come back (see below), people who have good kidney function 6-12 months after getting the disease generally do very well.

Once someone has had the anti-GBM disease, a relapse of the disease is uncommon. However, 20-30% of people who have the anti-GBM disease are also found to have another kind of autoantibody in their blood, called ANCA (which stands for anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies). ANCA antibodies are associated with a different disease (ANCA vasculitis). In these 20-30% of patients with the anti-GBM disease who also have ANCA antibodies in their blood, there is a much higher risk of the disease coming back or flaring again in the future. For this reason, testing for ANCA should be done in all patients with the anti-GBM disease. For most people with the anti-GBM disease who do not have ANCA antibodies, the disease rarely relapses once it happens (about 2-3%).

Kidney Transplant in Anti-GBM Disease

When anti-GBM disease involves the kidneys, it can often lead to kidney failure. Fortunately, a kidney transplant is an option for these patients.

Read general information about kidney transplants here.

Treatment of anti-GBM disease is focused on removing the anti-GBM antibody from the blood. Before having a kidney transplant, it is recommended that patients wait at least 6 months after finishing treatment and clearing the anti-GBM antibody from their blood. Once the disease is no longer active, a transplant is a great option for many people. The chance that the anti-GBM disease will come back in the kidney is very low, occurring in less than 5% of patients. If it does come back in a transplanted kidney, the treatment is similar to what is done when it happens the first time in someone’s own kidneys – including plasmapheresis, corticosteroids, and cyclophosphamide.

References