Breathing control its main function is to send signals to the muscles that control respiration to cause breathing to occur. The ventral respiratory group stimulates expiratory movements. The dorsal respiratory group stimulates inspiratory movements.

The control of ventilation refers to the physiological mechanisms involved in the control of breathing, which is the movement of air into and out of the lungs. Ventilation facilitates respiration. Respiration refers to the utilization of oxygen and balancing of carbon dioxide by the body as a whole, or by individual cells in cellular respiration.[rx]

The most important function of breathing is supplying of oxygen to the body and balancing the carbon dioxide levels. Under most conditions, the partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PCO2), or concentration of carbon dioxide, controls the respiratory rate.

Neural Mechanisms (Respiratory Center)

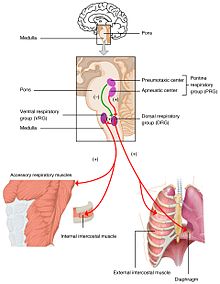

The medulla and the pons are involved in the regulation of the ventilatory pattern of respiration.

Key Points

The ventral respiratory group controls voluntarily forced exhalation and acts to increase the force of inspiration.

The dorsal respiratory group (nucleus tractus solitarius) controls mostly inspiratory movements and their timing.

Ventilatory rate (minute volume) is tightly controlled and determined primarily by blood levels of carbon dioxide as determined by metabolic rate.

Chemoreceptors can detect changes in blood pH that require changes in involuntary respiration to correct. The apneustic (stimulating) and pnuemotaxic (limiting) centers of the pons work together to control the rate of breathing.

The medulla sends signals to the muscles that initiate inspiration and expiration and controls nonrespiratory air movement reflexes, like coughing and sneezing.

Key Terms

- respiratory control centers: The medulla sends signals to the muscles involved in breathing, and the pons control the rate of breathing.

- chemoreceptors: These are receptors in the medulla and in the aortic and carotid bodies of the blood vessels that detect changes in blood pH and signal the medulla to correct those changes.

Involuntary respiration is any form of respiratory control that is not under direct, conscious control. Breathing is required to sustain life, so involuntary respiration allows it to happen when voluntary respiration is not possible, such as during sleep. Involuntary respiration also has metabolic functions that work even when a person is conscious.

The Respiratory Centers

Anatomy of the brainstem: The brainstem, which includes the pons and medulla.

Involuntary respiration is controlled by the respiratory centers of the upper brainstem (sometimes termed the lower brain, along with the cerebellum). This region of the brain controls many involuntary and metabolic functions besides the respiratory system, including certain aspects of cardiovascular function and involuntary muscle movements (in the cerebellum).

The respiratory centers contain chemoreceptors that detect pH levels in the blood and send signals to the respiratory centers of the brain to adjust the ventilation rate to change acidity by increasing or decreasing the removal of carbon dioxide (since carbon dioxide is linked to higher levels of hydrogen ions in the blood).

There are also peripheral chemoreceptors in other blood vessels that perform this function as well, which include the aortic and carotid bodies.

The Medulla

The medulla oblongata is the primary respiratory control center. Its main function is to send signals to the muscles that control respiration to cause breathing to occur. There are two regions in the medulla that control respiration:

- The ventral respiratory group stimulates expiratory movements.

- The dorsal respiratory group stimulates inspiratory movements.

The medulla also controls the reflexes for nonrespiratory air movements, such as coughing and sneezing reflexes, as well as other reflexes, like swallowing and vomiting.

The Pons

The pons is the other respiratory center and is located underneath the medulla. Its main function is to control the rate or speed of involuntary respiration. It has two main functional regions that perform this role:

- The apneustic center sends signals for inspiration for long and deep breaths. It controls the intensity of breathing and is inhibited by the stretch receptors of the pulmonary muscles at a maximum depth of inspiration, or by signals from the pnuemotaxic center. It increases tidal volume.

- The pnuemotaxic center sends signals to inhibit inspiration that allows it to finely control the respiratory rate. Its signals limit the activity of the phrenic nerve and inhibit the signals of the apneustic center. It decreases tidal volume.

The apneustic and pnuemotaxic centers work against each other together to control the respiratory rate.

Neural Mechanisms (Cortex)

The cerebral cortex of the brain controls voluntary respiration.

Key Points

The motor cortex within the cerebral cortex of the brain controls voluntary respiration (the ascending respiratory pathway).

Voluntary respiration may be overridden by aspects of involuntary respiration, such as chemoreceptor stimulus, and hypothalamus stress response.

The phrenic nerves, vagus nerves, and posterior thoracic nerves are the major nerves involved in respiration.

Voluntary respiration is needed to perform higher functions, such as voice control.

Key Terms

- The Phrenic Nerves: A set of two nerves that brings nerve impulses from the spinal cord to the diaphragm.

- primary motor cortex: The region in the brain that initiates all voluntary muscular movement, including those for respiration.

Voluntary respiration is any type of respiration that is under conscious control. Voluntary respiration is important for the higher functions that involve air supply, such as voice control or blowing out candles. Similar to how involuntary respiration’s lower functions are controlled by the lower brain, voluntary respiration’s higher functions are controlled by the upper brain, namely parts of the cerebral cortex.

The Motor Cortex

The primary motor cortex is the neural center for voluntary respiratory control. More broadly, the motor cortex is responsible for initiating any voluntary muscular movement.

The processes that drive its functions aren’t fully understood, but it works by sending signals to the spinal cord, which sends signals to the muscles it controls, such as the diaphragm and the accessory muscles for respiration. This neural pathway is called the ascending respiratory pathway.

Different parts of the cerebral cortex control different forms of voluntary respiration. Initiation of the voluntary contraction and relaxation of the internal and external intercostal muscles takes place in the superior portion of the primary motor cortex.

The center for diaphragm control is posterior to the location of thoracic control (within the superior portion of the primary motor cortex). The inferior portion of the primary motor cortex may be involved in controlled exhalation.

Activity has also been seen within the supplementary motor area and the premotor cortex during voluntary respiration. This is most likely due to the focus and mental preparation of the voluntary muscular movement that occurs when one decides to initiate that muscle movement.

Note that voluntary respiratory nerve signals in the ascending respiratory pathway can be overridden by chemoreceptor signals from involuntary respiration. Additionally, other structures may override voluntary respiratory signals, such as the activity of limbic center structures like the hypothalamus.

During periods of perceived danger or emotional stress, signals from the hypothalamus take over the respiratory signals and increase the respiratory rate to facilitate the fight or flight response.

Topography of the primary motor cortex: Topography of the primary motor cortex, on an outline drawing of the human brain. Each part of the primary motor cortex controls a different part of the body.

Nerves Used in Respiration

There are several nerves responsible for the muscular functions involved in respiration. There are three types of important respiratory nerves:

- The phrenic nerves – The nerves that stimulate the activity of the diaphragm. They are composed of two nerves, the right and left phrenic nerve, which passes through the right and left side of the heart respectively. They are autonomic nerves.

- The vagus nerve – Innervates the diaphragm as well as movements in the larynx and pharynx. It also provides parasympathetic stimulation for the heart and the digestive system. It is a major autonomic nerve.

- The posterior thoracic nerves – These nerves stimulate the intercostal muscles located around the pleura. They are considered to be part of a larger group of intercostal nerves that stimulate regions across the thorax and abdomen. They are somatic nerves.

These three types of nerves continue the signal of the ascending respiratory pathway from the spinal cord to stimulate the muscles that perform the movements needed for respiration.

Damage to any of these three respiratory nerves can cause severe problems, such as diaphragm paralysis if the phrenic nerves are damaged. Less severe damage can cause irritation to the phrenic or vagus nerves, which can result in hiccups.

Chemoreceptor Regulation of Breathing

Chemoreceptors detect the levels of carbon dioxide in the blood by monitoring the concentrations of hydrogen ions in the blood.

Key Points

An increase in carbon dioxide concentration leads to a decrease in the pH of blood due to the production of H+ ions from carbonic acid.

In response to a decrease in blood pH, the respiratory center (in the medulla ) sends nervous impulses to the external intercostal muscles and the diaphragm, to increase the breathing rate and the volume of the lungs during inhalation.

Hyperventilation causes alakalosis, which causes a feedback response of decreased ventilation (to increase carbon dioxide), while hypoventilation causes acidosis, which causes a feedback response of increased ventilation (to remove carbon dioxide).

Any situation with hypoxia (too low oxygen levels) will cause a feedback response that increases ventilation to increase oxygen intake.

Vomiting causes alkalosis and diarrhea causes acidosis, which will cause an appropriate respiratory feedback response.

Key Terms

- hypoxia: A system-wide deficiency in the levels of oxygen that reach the tissues.

- central chemoreceptors: Located within the medulla, they are sensitive to the pH of their environment.

- peripheral chemoreceptors: The aortic and carotid bodies, which act principally to detect variation of the oxygen concentration in the arterial blood, also monitor arterial carbon dioxide and pH.

Chemoreceptor regulation of breathing is a form of negative feedback. The goal of this system is to keep the pH of the bloodstream within normal neutral ranges, around 7.35.

Chemoreceptors

A chemoreceptor, also known as a chemosensor, is a sensory receptor that transduces a chemical signal into an action potential. The action potential is sent along nerve pathways to parts of the brain, which are the integrating centers for this type of feedback. There are many types of chemoreceptors in the body, but only a few of them are involved in respiration.

The respiratory chemoreceptors work by sensing the pH of their environment through the concentration of hydrogen ions. Because most carbon dioxide is converted to carbonic acid (and bicarbonate ) in the bloodstream, chemoreceptors are able to use blood pH as a way to measure the carbon dioxide levels of the bloodstream.

The main chemoreceptors involved in respiratory feedback are:

- Central chemoreceptors: These are located on the ventrolateral surface of the medulla oblongata and detect changes in the pH of spinal fluid. They can be desensitized over time from chronic hypoxia (oxygen deficiency) and increased carbon dioxide.

- Peripheral chemoreceptors: These include the aortic body, which detects changes in blood oxygen and carbon dioxide, but not pH, and the carotid body which detects all three. They do not desensitize and have less of an impact on the respiratory rate compared to the central chemoreceptors.

Chemoreceptor Negative Feedback

Negative feedback responses have three main components: the sensor, the integrating sensor, and the effector. For the respiratory rate, the chemoreceptors are the sensors for blood pH, the medulla and pons from the integrating center, and the respiratory muscles are the effector.

Consider a case in which a person is hyperventilating from an anxiety attack. Their increased ventilation rate will remove too much carbon dioxide from their body. Without that carbon dioxide, there will be less carbonic acid in the blood, so the concentration of hydrogen ions decreases and the pH of the blood rises, causing alkalosis.

In response, the chemoreceptors detect this change and send a signal to the medulla, which signals the respiratory muscles to decrease the ventilation rate so carbon dioxide levels and pH can return to normal levels.

There are several other examples in which chemoreceptor feedback applies. A person with severe diarrhea loses a lot of bicarbonate in the intestinal tract, which decreases bicarbonate levels in the plasma. As bicarbonate levels decrease while hydrogen ion concentrations stay the same, blood pH will decrease (as bicarbonate is a buffer) and become more acidic.

In cases of acidosis, feedback will increase ventilation to remove more carbon dioxide to reduce the hydrogen ion concentration. Conversely, vomiting removes hydrogen ions from the body (as the stomach contents are acidic), which will cause decreased ventilation to correct alkalosis.

Chemoreceptor feedback also adjusts for oxygen levels to prevent hypoxia, though only the peripheral chemoreceptors sense oxygen levels. In cases where oxygen intake is too low, feedback increases ventilation to increase oxygen intake.

A more detailed example would be that if a person breathes through a long tube (such as a snorkeling mask) and has increased amounts of dead space, feedback will increase ventilation.

Respiratory feedback: The chemoreceptors are the sensors for blood pH, the medulla and pons form the integrating center, and the respiratory muscles are the effector.

Proprioceptor Regulation of Breathing

The Hering–Breuer inflation reflex prevents overinflation of the lungs.

Key Points

Pulmonary stretch receptors present in the smooth muscle of the airways and the pleura respond to excessive stretching of the lung during large inspirations.

The Hering–Breuer inflation reflex is initiated by stimulation of

stretch receptors. The deflation reflex is initiated by stimulation

of the compression receptors (called proprioceptors) or deactivation of

stretch receptors when the lungs deflate.Activation of the pulmonary stretch receptors (via the vagus nerve ) results in inhibition of the inspiratory stimlus in the medulla, and thus inhibition of inspiration and initiation of expiration.

An increase in pulmonary stretch receptor activity leads to an elevation of heart rate ( tachycardia ).

A cyclical, elevated heart rate from inspiration is called sinus arrhythmia and is a normal response in youth. Inhibition of inspiration is important to allow expiration to occur.

Key Terms

- sinus arrhythmia: A normal cyclical heart rate change in which an increase in heart rate occurs during inspiration, but returns to normal during expiration.

- pulmonary stretch receptors: A sensory receptor that sends an action potential when it detects pressure, tension, stretch, or distortion.

The lungs are a highly elastic organ capable of expanding to a much larger volume during inflation. While the volume of the lungs is proportional to the pressure of the pleural cavity as it expands and contracts during breathing, there is a risk of over-inflation of the lungs if inspiration becomes too deep for too long. Physiological mechanisms exist to prevent over-inflation of the lungs.

The Hering–Bauer Reflex

Cardiac and respiratory branches of the vagus nerve: The vagus nerve is the neural pathway for stretch receptor regulation of breathing.

The Hering–Breuer reflex (also called the inflation reflex) is triggered to prevent over-inflation of the lungs. There are many stretch receptors in the lungs, particularly within the pleura and the smooth muscles of the bronchi and bronchioles, that activate when the lungs have inflated to their ideal maximum point.

These stretch receptors are mechanoreceptors, which are a type of sensory receptor that specifically detects mechanical pressure, distortion, and stretch, and are found in many parts of the human body, especially the lungs, stomach, and skin. They do not detect fine-touch information like most sensory receptors in the human body, but they do create a feeling of tension or fullness when activated, especially in the lungs or stomach.

When the lungs are inflated to their maximum volume during inspiration, the pulmonary stretch receptors send an action potential signal to the medulla and pons in the brain through the vagus nerve.

The pneumatic center of the pons sends signals to inhibit the apneustic center of the pons, so it doesn’t activate the inspiratory area (the dorsal medulla), and the inspiratory signals that are sent to the diaphragm and accessory muscles stop. This is called the inflation reflex.

As inspiration stops, expiration begins and the lung begins to deflate. As the lungs deflate the stretch receptors are deactivated (and compression receptors called proprioceptors may be activated) so the inhibitory signals stop and inhalation can begin again—this is called the deflation reflex.

Early physiologists believed this reflex played a major role in establishing the rate and depth of breathing in humans. While this may be true for most animals, it is not the case for most adult humans at rest. However, the reflex may determine the breathing rate and depth in newborns and in adult humans when tidal volume is more than 1 L, such as when exercising.

Additionally, people with emphysema have an impaired Hering–Bauer reflex due to a loss of pulmonary stretch receptors from the destruction of lung tissue, so their lungs can over-inflate as well as collapse, which contributes to shortness of breath.

Sinus Arrhythmia

As the Hering–Bauer reflex uses the vagus nerve as its neural pathway, it also has a few cardiovascular system effects because the vagus nerve also innervates the heart.

During stretch receptor activation, the inhibitory signal that travels through the vagus nerve is also sent to the sinus-atrial node of the heart. Its stimulation causes a short-term increase in resting heart rate, which is called tachycardia.

The heart rate returns to normal during expiration when the stretch receptors are deactivated. When this process is cyclical it is called a sinus arrhythmia, which is a generally normal physiological phenomenon in which there is short-term tachycardia during inspiration.

Sinus arrhythmias do not occur in everyone and are more common in youth. The sensitivity of the sinus-atrial node to the inflation reflex is lost over time, so sinus arrhythmias are less common in older people.

Control of respiratory rhythm

Ventilatory pattern

Breathing is normally an unconscious, involuntary, automatic process. The pattern of motor stimuli during breathing can be divided into an inhalation stage and an exhalation stage. Inhalation shows a sudden, ramped increase in motor discharge to the respiratory muscles (and the pharyngeal constrictor muscles).[rx] Before the end of inhalation, there is a decline in, and end of motor discharge. Exhalation is usually silent, except at high respiratory rates.

The respiratory center in the medulla and pons of the brainstem controls the rate and depth of respiration, (the respiratory rhythm), through various inputs. These include signals from the peripheral chemoreceptors and central chemoreceptors; from the vagus nerve and glossopharyngeal nerve carrying input from the pulmonary stretch receptors, and other mechanoreceptors in the lungs.[rx][rx] as well as signals from the cerebral cortex and hypothalamus.

Medulla

- ventral respiratory group (includes the pre-Bötzinger complex). The ventral respiratory group controls voluntarily forced exhalation and acts to increase the force of inhalation. Regulates rhythm of inhalation and exhalation.

- dorsal respiratory group (solitary nucleus). The dorsal respiratory group controls mostly movements of inhalation and their timing.

Pons

- pneumotaxic center.

- Coordinates speed of inhalation and exhalation

- Sends inhibitory impulses to the inspiratory area

- Involved in fine-tuning of respiration rate.

apneustic center

- Coordinates speed of inhalation and exhalation.

- Sends stimulatory impulses to the inspiratory area – activates and prolongs inhalations

- Overridden by pneumatic control from the apneustic area to end inhalation

Control of ventilatory pattern

Ventilation is normally unconscious and automatic but can be overridden by conscious alternative patterns.[rx] Thus the emotions can cause yawning, laughing, sighing (etc.), social communication causes speech, song, and whistling, while entirely voluntary overrides are used to blow out candles, and breath-holding (for instance, to swim underwater). Hyperventilation may be entirely voluntary or in response to emotional agitation or anxiety when it can cause the distressing hyperventilation syndrome. The voluntary control can also influence other functions such as the heart rate as in yoga practices and meditation.[rx]

The ventilatory pattern is also temporarily modified by complex reflexes such as sneezing, straining, burping, coughing and vomiting.

Determinants of ventilatory rate

Ventilatory rate (respiratory minute volume) is tightly controlled and determined primarily by blood levels of carbon dioxide as determined by metabolic rate. Blood levels of oxygen become important in hypoxia. These levels are sensed by central chemoreceptors on the surface of the medulla oblongata for increased pH (indirectly from the increase of carbon dioxide in cerebrospinal fluid), and the peripheral chemoreceptors in the arterial blood for oxygen and carbon dioxide. Afferent neurons from the peripheral chemoreceptors are via the glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX) and the vagus nerve (CN X).

The concentration of CO2 rises in the blood when the metabolic use of O2, and the production of CO2 is increased during, for example, exercise. The CO2 in the blood is transported largely as bicarbonate (HCO3−) ions, by conversion first to carbonic acid (H2CO3), by the enzyme carbonic anhydrase, and then by disassociation of this acid to H+ and HCO3−. Build-up of CO2 therefore causes an equivalent build-up of the disassociated hydrogen ions, which, by definition, decreases the pH of the blood. The pH sensors on the brain stem immediately respond to this fall in pH, causing the respiratory center to increase the rate and depth of breathing. The consequence is that the partial pressure of CO2 (PCO2) does not change from rest going into exercise. During very short-term bouts of intense exercise the release of lactic acid into the blood by the exercising muscles causes a fall in the blood plasma pH, independently of the rise in the PCO2, and this will stimulate pulmonary ventilation sufficiently to keep the blood pH constant at the expense of a lowered PCO2.

Mechanical stimulation of the lungs can trigger certain reflexes as discovered in animal studies. In humans, these seem to be more important in neonates and ventilated patients, but of little relevance in health. The tone of respiratory muscle is believed to be modulated by muscle spindles via a reflex arc involving the spinal cord.

Drugs can greatly influence the rate of respiration. Opioids and anesthetics tend to depress ventilation, by decreasing the normal response to raised carbon dioxide levels in the arterial blood. Stimulants such as amphetamines can cause hyperventilation.

Pregnancy tends to increase ventilation (lowering plasma carbon dioxide tension below normal values). This is due to increased progesterone levels and results in enhanced gas exchange in the placenta.

Feedback control

Receptors play important roles in the regulation of respiration and include the central and peripheral chemoreceptors, and pulmonary stretch receptors, a type of mechanoreceptor.

- Central chemoreceptors of the central nervous system, located on the ventrolateral medullary surface, are sensitive to the pH of their environment.[rx][rx]

- Peripheral chemoreceptors act most importantly to detect variation of the PO2 in the arterial blood, in addition to detecting arterial PCO2 and pH.

- Mechanoreceptors are located in the airways and parenchyma and are responsible for a variety of reflex responses. These include:

- The Hering-Breuer reflex terminates inhalation to prevent overinflation of the lungs, and the reflex responses of coughing, airway constriction, and hyperventilation.

- The upper airway receptors are responsible for reflex responses such as sneezing, coughing, closure of the glottis, and hiccups.

- The spinal cord reflex responses include the activation of additional respiratory muscles as compensation, gasping response, hypoventilation, and an increase in breathing frequency and volume.

- The nasopulmonary and mesothoracic reflexes regulate the mechanism of breathing through deepening the inhale. Triggered by the flow of the air, the pressure of the air in the nose, and the quality of the air, impulses from the nasal mucosa are transmitted by the trigeminal nerve to the respiratory center in the brainstem, and the generated response is transmitted to the bronchi, the intercostal muscles and the diaphragm.