Lumbosacral Disc Herniation/Intervertebral Disc Herniation is a common problem in the lumbar and cervical spine that can cause varying symptoms such as pain, numbness, and weakness of both the upper and lower extremities. Intervertebral disc herniation is defined as a condition in which the nucleus pulposus is protruding past the annulus fibrosus. This herniation can be on a spectrum of partial to complete depending upon how much of the NP herniates through the AF.[rx] Disc herniation is most common in the lumbar spine followed by the cervical spine. A high rate of disc herniation in the lumbar and cervical spine can be explained by an understanding of the biomechanical forces in the flexible part of the spine. The thoracic spine has a lower rate of disc herniation.[rx][rx]

Herniated lumbar disc is a displacement of disc material (nucleus pulposus or annulus fibrosis) beyond the intervertebral disc space. The diagnosis can be confirmed by radiological examination. However, magnetic resonance imaging findings of a herniated disc are not always accompanied by clinical symptoms. This review covers the treatment of people with clinical symptoms relating to confirmed or suspected disc herniation. It does not include the treatment of people with spinal cord compression, or people with cauda equina syndrome, which require emergency intervention. [rx][rx][rx][rx][rx]

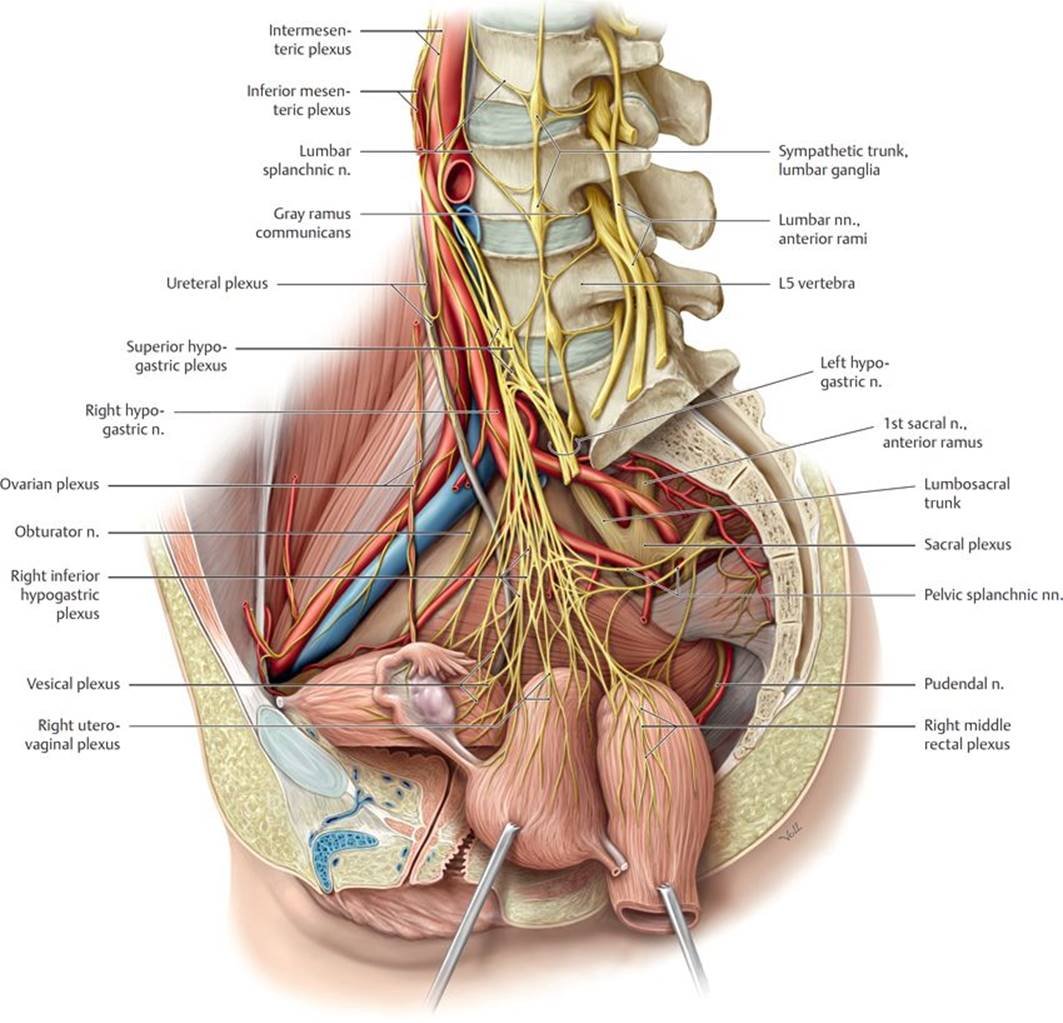

Anatomy Of Intervertebral Disc Herniation

We summarize the anatomy, motor function, sensitive distribution, and reflex of the most commons nerve roots involved in cervical and lumbosacral nucleus pulposus herniation:

Cervical

-

C5 nerve root – Exits between C4 and C5 foramina, innervates deltoids and biceps (with C6), sensory distribution: lateral arm (axillary nerve) and is assessed with biceps reflex.

-

C6 nerve root– Exits between C5 and C6 foramina, innervates biceps (with C5) and wrist extensors, sensory distribution – lateral forearm (musculocutaneous nerve), assessed with brachioradialis reflex.

-

C7 nerve root – Exits between C6 and C7 foramina, innervates triceps, wrist flexors, and finger extensors, sensory distribution, middle finger, assessed with triceps reflex.

-

C8 nerve root – Exits between C7 and T1 foramina, innervates interosseus muscles and finger flexors, sensory distribution: ring and little fingers and distal half of the forearm (ulnar side), no reflex.

Lumbosacral

-

L1 nerve root – Exits between L1 and L2 foramina, innervates iliopsoas muscle, sensory distribution: upper third thigh, assessed with the cremasteric reflex (male).

-

L2 nerve root – Exits between L2 and L3 foramina, innervates iliopsoas muscle, hip adductor, and quadriceps, sensory distribution: middle third thigh, no reflex.

-

L3 nerve root – Exits between L3 and L4 foramina, innervates iliopsoas muscle, hip adductor, and quadriceps, sensory distribution: lower third thigh, no reflex.

-

L4 nerve root – Exits between L4 and L5 foramina, innervates quadriceps and tibialis anterior, sensory distribution: anterior knee, medial side of the leg, assessed with patellar reflex.

-

L5 nerve root – Exits between L5 and S1 foramina, innervates extensor hallucis longus, extensor digitorum longus, and brevis, and gluteus medius, sensory distribution: anterior leg, lateral leg, and dorsum of the foot, no reflex.

-

S1 nerve root – Exits between S1 and S2 foramina, innervates gastrocnemius, soleus, and gluteus maximus, sensitive distribution: posterior thigh, plantar region, assessed with Achilles reflex.

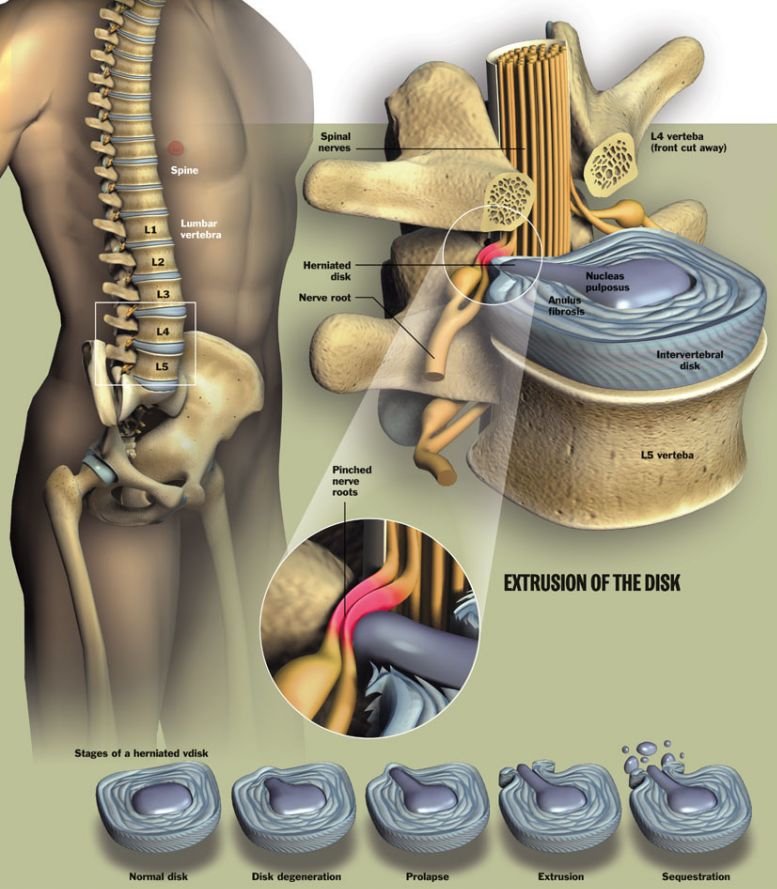

Disc herniation material (i.e. herniated nucleus pulposus, HNP)

-

Varying degrees of HNP is recognized, from disc protrusion (annulus remains intact), extrusion (annular compromise, but herniated material remains continuous with disc space), to sequestered (free) fragments

-

HNP material predictably is resorbed over time, with the sequestered fragment demonstrating the highest degree of resorption potential

-

In general, 90% of patients will have an asymptomatic improvement in radicular symptoms within 3 months following nonoperative protocols alone

Hypertrophy/expansion of degenerative tissues

-

Common sources include ligamentum flavum and the facet joint. The facet joint itself undergoes degenerative changes (just like any other joint in the body) and synovial hypertrophy and/or associated cysts can compromise surrounding nerve roots.

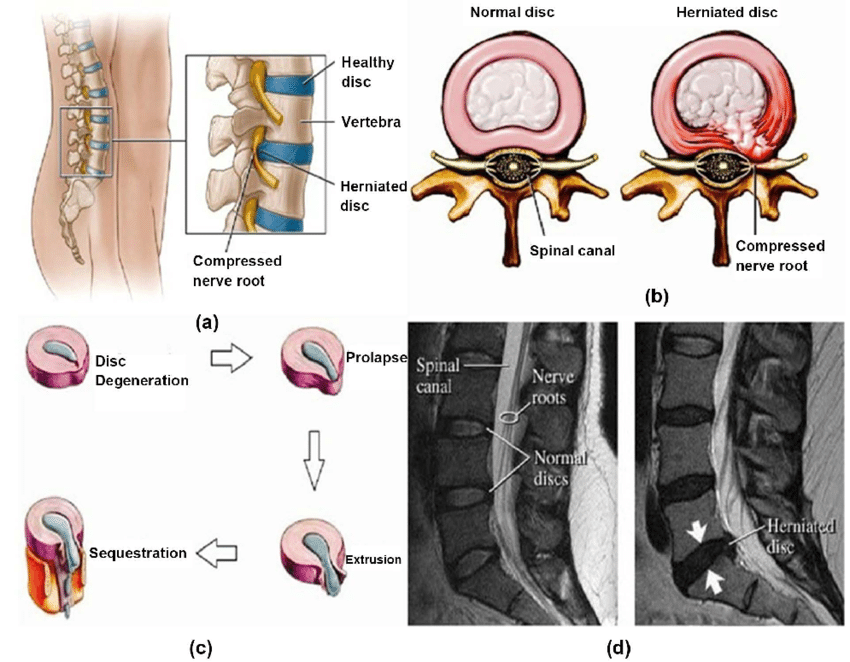

Types of Intervertebral Disc Herniation

Doctors categorize slipped disks by severity

- Disc Degeneration – Chemical changes associated with aging causes discs to weaken, but without a herniation.

- Bulging disk – With age, the intervertebral disk may lose fluid and become dried out. As this happens, the spongy disk (which is located between the bony parts of the spine and acts as a “shock absorber”) becomes compressed. This may lead to the breakdown of the tough outer ring. This lets the nucleus, or the inside of the ring, to bulge out. This is called a bulging disk.

-

Protrusion –The disk bulges out between the vertebrae, but its outermost layer is still intact.

-

Extrusion – There is a tear in the outermost layer of the spinal disk, causing spinal disk tissue to spill out. But the tissue that has come out is still connected to the disk.

-

Sequestration – Spinal disk tissue has entered the spinal canal and is no longer directly attached to the disk.

-

Ruptured or herniated disk – As the disk continues to break down, or with continued stress on the spine, the inner nucleus pulposus may actually rupture out from the annulus. This is a ruptured, or herniated, disk. The fragments of disc material can then press on the nerve roots located just behind the disk space. This can cause pain, weakness, numbness, or changes in sensation.

A disc herniation at the L5/S1 level can have two overlapping presentations

- L5 at the L5/S1 level – a disc herniation far laterally into the left/right neural foramen would compress the L5 nerve, resulting in weakness of hip abduction muscles, ankle dorsiflexion (anterior tibialis muscle) and/or extension of the great toe (extensor hallucis longus muscle).

- S1 at the L5/S1 level – a disc herniation centrally into the canal would compress the S1 nerve, resulting in weakness of ankle plantar flexion (gastrocnemius muscle).

- Asymptomatic Annular Tear – If the annular tear or fissure is identified incidentally, most commonly on MRI imaging, then no treatment is warranted. Such annular fissures may resolve spontaneously over time and are frequently due to the stresses applied to the spine. It is posited that some asymptomatic annular tears may become symptomatic with time, but there is currently no definitive evidence that the treatment of asymptomatic annular tears provides any benefit or prevents any future issues.

- Symptomatic Annular Tear without Disc Protrusion or Herniation – An annular fissure or tear can be symptomatic without disc protrusion or herniation. It is suspected that local inflammatory reactions from the annulus fibrosus tear or fissure lead to irritation of adjacent nerve fibers or traversing nerve roots. The mainstay of treatment for such situations is non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications as well as low-impact physical therapy.

Causes of Intervertebral Disc Herniation

The differential diagnosis for lumbosacral radiculopathy should include (but is not limited to) the following

Degenerative conditions of the spine (most common causes)

-

Spondylolisthesis – in the degenerative setting, this occurs as a result of a pathologic cascade including intervertebral disc degeneration, ensuing intersegmental instability, and facet joint arthropathy

-

Spinal stenosis

-

Adult isthmic spondylolisthesis – is typically caused by an acquired defect in the par interarticularis

-

Pars defects (i.e. spondylolysis) in adults are most often secondary to repetitive microtrauma.

-

-

Clinicians should recognize spinal fractures can occur in younger, healthy patient populations secondary to high-energy injuries (e.g. MVA, fall from height) or secondary low energy injuries and spontaneous fractures in the elderly populations, including any patient with osteoporosis

-

Associated hemorrhage from the injury can result in a deteriorating clinical and neurologic exam.

-

Benign or malignant tumors

-

Metastatic tumors (most common)

-

Primary tumors

-

Ependymoma

-

Schwannoma

-

Neurofibroma

-

Lymphoma

-

Lipomas

-

Paraganglioma

-

Ganglioneuroma

-

Osteoblastoma

-

-

Infection

-

Osteodiscitis

-

Osteomyelitis

-

Epidural abscess

-

Fungal infections (e.g. Tuberculosis)

-

Other infections: lyme disease, HIV/AIDS-defining ilnesses, Herpes zoster (HZ)

-

-

Vascular conditions

-

Hemangioblastoma, aterior-venous malformations (AVM)[rx]

-

-

Cauda equina syndrome

-

History: Progressive motor/sensory loss, new urinary retention or incontinence, new fecal incontinence

-

Physical exam: Saddle anesthesia, anal sphincter atony, significant motor deficits of multiple myotomes

-

-

Fracture

-

History: Significant trauma (relative to age), Prolonged corticosteroid use, osteoporosis, and age greater than 70 years

-

Physical exam: Contusions, abrasions, tenderness to palpation over spinous processes

-

-

Infection

-

History: Spinal procedure within the last 12 months, Intravenous drug use, Immunosuppression, prior lumbar spine surgery

-

Physical exam: Fever, wound in the spinal region, localized pain, and tenderness

-

-

Malignancy

-

History: History of metastatic cancer, unexplained weight loss

-

Physical exam: Focal tenderness to palpation in the setting of risk factors

-

Pediatric red flags are the same as adults with a few notable differences[rx][rx]:

-

Malignancy

-

History: age less than 4 years, nighttime pain

-

-

Infectious

-

History: age less than 4 years, nighttime pain, history of tuberculosis exposure

-

-

Inflammatory

-

History: age less than 4 years, morning stiffness for greater than 30min, improving with activity or hot showers

-

-

Fracture

-

History: activities with repetitive lumber hyperextension (sports such as cheerleading, gymnastics, wrestling, or football linemen)

-

Physical exam: Tenderness to palpation over spinous process, positive Stork test

-

Evaluating clinicians must first rule out associated “red flag” symptoms including:

-

Thoracic pain

-

Fever/unexplained weight loss

-

Night sweats

-

Bowel or bladder dysfunction

-

Malignancy (document/record any previous surgeries, chemo/radiation, recent scans and bloodwork, and history of metastatic disease)

-

Can be seen in association with pain at night, pain at rest, unexplained weight loss, or night sweats

-

-

Significant medical comorbidities

-

Neurologic deficit or serial exam deterioration

-

Gait ataxia

-

Saddle anesthesia

-

Age of onset (bimodal — Age < 20 years or Age > 55 years)

Symptoms of Intervertebral Disc Herniation

Cervical and thoracic disc herniation can also exhibit symptoms of myelopathy such as spasticity, clumsiness, wide-based gate, and weakness, on physical examination hyperreflexia is the most important sign. The Lhermitte sign is the presence of an electric shock-like sensation towards the back and lower extremities, especially by flexing the neck.[rx][rx] Bowel and bladder dysfunction may indicate poor prognosis.

The primary signs and symptoms of

- LDH is radicular pain – sensory abnormalities, and weakness in the distribution of one or more lumbosacral nerve roots [rx, rx]. Focal paresis, restricted trunk flexion, and increases in leg pain with straining, coughing, and sneezing are also indicative [rx, rx]. Patients frequently report increased pain when sitting, which is known to increase disc pressure by nearly 40% [rx].

- Pain that is relieved with sitting for forwarding flexion – is more consistent with lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS), as the latter motion increases disc pressure by 100–400% and would likely increase pain in isolated LDH [rx]. Rainville et al. recently compared signs of LDH with LSS and found that LSS patients are more likely to have increased medical comorbidities, lower levels of disability and leg pain, abnormal Achilles reflexes, and pain primarily in the posterior knee [rx].

The type and location of your symptoms depend on the location and direction of the herniated disc, and the amount of pressure on nearby nerves. A herniated disc may cause no pain at all. Or, it can cause any of the following symptoms:

- Numbness or tingling – People who have a herniated disk often have radiating numbness or tingling in the body part served by the affected nerves.

- Weakness – Muscles served by the affected nerves tend to weaken. This can cause you to stumble, or affect your ability to lift or hold items.

- Pain in the neck, back, low back, arms, or legs

- Inability to bend or rotate the neck or back

- Numbness or tingling in the neck, shoulders, arms, hands, hips, legs, or feet

- Weakness in the arms or legs

- Limping when walking

- Increased pain when coughing, sneezing, reaching, or sitting

- Inability to stand up straight; being “stuck” in a position, such as stooped forward or leaning to the side

- Difficulty getting up from a chair

- Inability to remain in 1 position for a long period of time, such as sitting or standing, due to pain

- Pain that is worse in the morning

- This is a sharp, often shooting pain that extends from the buttock down the back of one leg. It is caused by pressure on the spinal nerve.

- Numbness or a tingling sensation in the leg and/or foot

- Weakness in the leg and/or foot

- Loss of bladder or bowel control. This is extremely rare and may indicate a more serious problem called cauda equina syndrome. This condition is caused by the spinal nerve roots being compressed.

The affect dermatome varies based on the level of herniation as well as herniation type. In paracentral herniation, the transversing nerve root is affected versus in far lateral herniations, the exiting nerve root is affected. For example, a paracentral herniation at L4-5 would cause L5 radiculopathy whereas a far lateral herniation at the same level would cause L4 radiculopathy.

Diagnosis of Intervertebral Disc Herniation

History

As part of the evaluation of neck pain, it is important to identify certain red flags that could be features of underlying inflammatory conditions, malignancy, or infection.[rx] These include:

-

Fever, chills

-

Night sweats

-

Unexplained weight loss

-

History of inflammatory arthritis, malignancy, systemic infection, tuberculosis, HIV, immunosuppression, or drug use

-

Unrelenting pain

-

Point tenderness over a vertebral body

-

Cervical lymphadenopathy

Physical Examination

- The clinician should assess the patient’s range of motion (ROM), as this can indicate the severity of pain and degeneration. A thorough neurological examination is necessary to evaluate sensory disturbances, motor weakness, and deep tendon reflex abnormalities. Careful attention should also focus on any sign of spinal cord dysfunction.

Typical findings of solitary nerve lesions due to compression by a herniated disc in the cervical spine

-

C2 Nerve – eye or ear pain, headache. History of rheumatoid arthritis or atlantoaxial instability

-

C3, C4 Nerve – vague neck, and trapezial tenderness and muscle spasms

-

C5 Nerve – neck, shoulder, and scapula pain. Lateral arm paresthesia. Primary motions affected include shoulder abduction and elbow flexion. May also observe weakness with shoulder flexion, external rotation, and forearm supination. Diminished biceps reflex.

-

C6 Nerve – neck, shoulder, and scapula pain. Paresthesia of the lateral forearm, lateral hand, and lateral two digits. Primary motions affected include elbow flexion and wrist extension. May also observe weakness with shoulder abduction, external rotation, and forearm supination and pronation — diminished brachioradialis reflex.

-

C7 Nerve – neck and shoulder pain. Paresthesia of the posterior forearm and third digit. Primary motions affected include elbow extension and wrist flexion. Diminished triceps reflex

-

C8 Nerve – neck and shoulder pain. Paresthesia of the medial forearm, medial hand, and medial two digits. Weakness during finger flexion, handgrip, and thumb extension.

Special Tests

- Lasègue’s Test

- Slump Test

- Muscle Weakness or Paresis

- Reflexes

- Hyperextension Test The patient needs to passively mobilize the trunk over the full range of extension, while the knees stay extended. The test indicates that the radiant pain is caused by disc herniation if the pan deteriorates.

- Manual Testing and Sensory Testing Look for hypoaesthesia, hypoalgesia, tingling, or numbness.

Lab Values

- RBS

- Serum creatinine

-

ESR and CRP – These are inflammatory markers that should be obtained If a chronic inflammatory condition is suspected (rheumatoid arthritis, polymyalgia rheumatic, seronegative spondyloarthropathy). These can also be beneficial if an infectious etiology is suspected.

-

CBC with differential – Useful to obtain in instances when infection or malignancy is suspected.

Radiological Imaging

- X-rays – The first test typically performed and one that is very accessible at most clinics and outpatient offices. Three views (AP, lateral, and oblique) views help assess the overall alignment of the spine as well as for the presence of any degenerative or spondylotic changes. These can be further supplemented with lateral flexion and extension views to assess for the presence of instability. If imaging demonstrates an acute fracture, this requires additional investigation using a CT scan or MRI. If there is a concern for atlantoaxial instability, the open mouth (odontoid) view may assist in diagnosis.

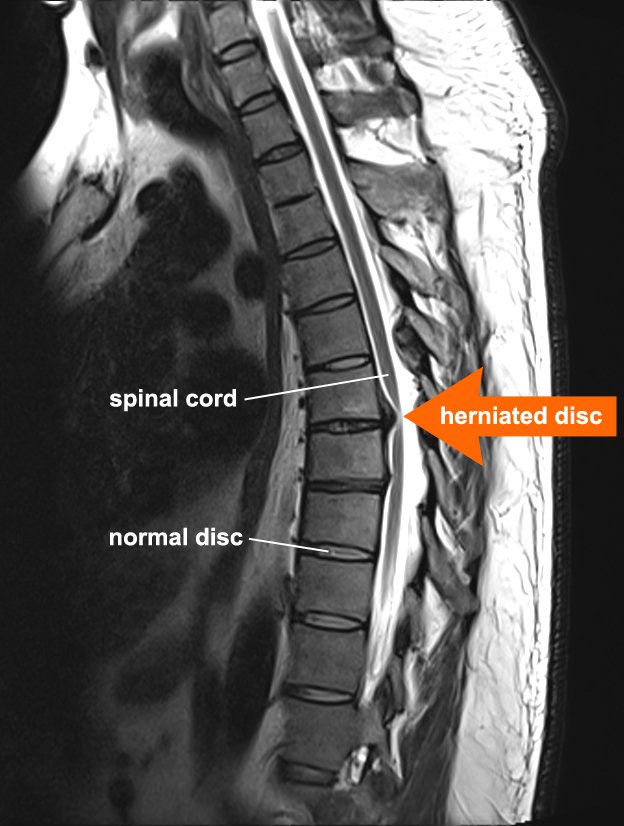

- CT Scan – This imaging is the most sensitive test to examine the bony structures of the spine. It can also show calcified herniated discs or any insidious process that may result in bony loss or destruction. In patients that are unable to or are otherwise ineligible to undergo an MRI, CT myelography can be used as an alternative to visualize a herniated disc.

- MRI – The preferred imaging modality and the most sensitive study to visualize a herniated disc, as it has the most significant ability to demonstrate soft-tissue structures and the nerve as it exits the foramen.

- Electrodiagnostic testing – (Electromyography and nerve conduction studies) can be an option in patients that demonstrate equivocal symptoms or imaging findings as well as to rule out the presence of a peripheral mononeuropathy. The sensitivity of detecting cervical radiculopathy with electrodiagnostic testing ranges from 50% to 71%.[rx]

- The straight leg raise test – With the patient lying supine, the examiner slowly elevates the patient’s led at an increasing angle, while keeping the leg straight at the knee joint. The test is positive if it reproduces the patient’s typical pain and paresthesia.[rx]

- The contralateral (crossed) straight leg raise test – As in the straight leg raise test, the patient is lying supine, and the examiner elevates the asymptomatic leg. The test is positive if the maneuver reproduces the patient’s typical pain and paresthesia. The test has a specificity greater than 90%.

- Myelography – An X-ray of the spinal canal following the injection of contrast material into the surrounding cerebrospinal fluid spaces will reveal the displacement of the contrast material. It can show the presence of structures that can cause pressure on the spinal cord or nerves, such as herniated discs, tumors, or bone spurs.

- Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) – The presence and severity of myelopathy can be evaluated by means of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), a neurophysiological method that measures the time required for a neural impulse to cross the pyramidal tracts, starting from the cerebral cortex and ending at the anterior horn cells of the cervical, thoracic, or lumbar spinal cord. This measurement is called the central conduction time (CCT).

- Electromyography and nerve conduction studies (EMG/NCS) – measure the electrical impulses along with nerve roots, peripheral nerves, and muscle tissue. Tests can indicate if there is ongoing nerve damage, if the nerves are in a state of healing from a past injury, or if there is another site of nerve compression. EMG/NCS studies are typically used to pinpoint the sources of nerve dysfunction distal to the spine.

- Other Studies – Patients with equivocal studies may opt for a discography when conservative measures fail. Electrophysiological studies can be performed to evaluate and elucidate the nerve roots affected by the injured cervical disc.[rx][rx]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for back pain is very broad, especially when considering the pediatric population. Below is a review of the more common diagnoses along with history or physical exam features that may increase your index of suspicion. This list is not comprehensive but represents the more likely and more concerning conditions that make up the differential.

Adults

-

Lumbosacral muscle strains/sprains

-

Presentation: follows traumatic incident or repetitive overuse, pain worse with movement, better with rest, restricted range of motion, tenderness to palpation of muscles

-

-

Lumbar spondylosis

-

Presentation: patient typically is greater than 40years old, pain may be present or radiate from hips, pain with extension or rotation, the neurologic exam is usually normal

-

-

Disk herniation

-

Presentation: usually involves the L4 to S1 segments, may include paresthesia, sensory change, loss of strength or reflexes depending on severity and nerve root involved

-

-

Spondylolysis, Spondylolisthesis

-

Presentation: similar to pediatrics, spondylolisthesis may present back pain with radiation to the buttock and posterior thighs, neuro deficits are usually in the L5 distribution

-

-

Vertebral compression fracture

-

Presentation: localized back pain worse with flexion, point tenderness on palpation, may be acute or occur insidiously over time, age, chronic steroid use, and osteoporosis are risk factors

-

-

Spinal stenosis

-

Presentation: back pain which can be accompanied by sensory loss or weakness in legs relieved with rest (neurologic claudication), neuro exam normal.

-

-

Tumor

-

Presentation: a history of metastatic cancer, unexplained weight loss, focal tenderness to palpation in the setting of risk factors

-

Clinical note: 97% of spinal tumors are metastatic disease; however, the provider should keep multiple myeloma in the differential

-

-

Infection – vertebral osteomyelitis, discitis, septic sacroiliitis, epidural abscess, paraspinal muscle abscess

-

Presentation: Spinal procedure within the last 12 months, Intravenous drug use, Immunosuppression, prior lumbar spine surgery, fever, wound in the spinal region, localized pain, and tenderness

-

Clinical note: Granulomatous disease may represent as high as one-third of cases in developing countries.

-

Pediatrics

-

Tumor

-

Presentation: fever, malaise, weight loss, nighttime pain, recent onset scoliosis

-

Clinical note: Osteoid osteoma is the most common tumor that presents with back pain – classically, the pain is promptly relieved with anti-inflammatory drugs such as NSAIDs

-

-

Infection – vertebral osteomyelitis, discitis, septic sacroiliitis, epidural abscess, paraspinal muscle abscess

-

Presentation: fever, malaise, weight loss, nighttime pain, recent onset scoliosis

-

Clinical notes: Epidural abscess should be a consideration with the presence of fever, spinal pain, and neurologic deficits or radicular pain; discitis may present with a patient refusing to walk or crawl

-

-

A herniated disk, slipped apophysis

-

Presentation: Acute pain, radicular pain, positive straight leg raise test, pain with spinal forward flexion, recent onset scoliosis

-

-

Spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis – lesion or injury to the posterior arch

-

Presentation: Acute pain, radicular pain, positive straight leg raise test, pain with spinal extension, tight hamstrings

-

-

Vertebral fracture

-

Presentation: acute pain, other injuries, traumatic mechanism of injury, neurologic loss

-

-

Muscle strain

-

Presentation: acute pain, muscle tenderness without radiation

-

-

Scheuermann’s kyphosis

-

Presentation: chronic pain, rigid kyphosis

-

-

Inflammatory spondyloarthropathies

-

Presentation: chronic pain, morning stiffness lasting greater than 30min, sacroiliac joint tenderness

-

-

Psychological Disorder – (conversion, somatization disorder)

-

Presentation: normal evaluation but persistent subjective pain

-

-

Idiopathic Scoliosis

-

Presentation: positive Adam’s test (for larger angle curvature), most commonly asymptomatic

-

Treatment Of Intervertebral Disc Herniation

Patient Education

-

Use of hot or cold packs for comfort and to decreased inflammation

-

Avoidance of inciting activities or prolonged sitting/standing

-

Practicing good, erect posture

-

Engaging in exercises to increase core strength

-

Gentle stretching of the lumbar spine and hamstrings

-

Regular light exercises such as walking, swimming, or aromatherapy

-

Use of proper lifting techniques

Non-Pharmacological Treatment

Conservative Treatments – Acute cervical or lumber radiculopathies secondary to a herniated disc are typically managed with non-surgical treatments as the majority of patients (75 to 90%) will improve. Modalities that can be used include[rx][rx][rx]:

- Rest the area by avoiding any activity that causes worsening symptoms in the arms or legs.

- Stay active around the house, and go on short walks several times per day. The movement will decrease pain and stiffness and help you feel better.

- Apply ice packs to the affected area for 15 to 20 minutes every 2 hours.

- Sit in firm chairs. Soft couches and easy chairs may make your problems worse.

-

Deep tissue massage may be helpful

-

Acupuncture – In acupuncture, the therapist inserts fine needles into certain points on the body with the aim of relieving pain.

-

Reiki – Reiki is a Japanese treatment that aims to relieve pain by using specific hand placements.

-

Moxibustion – This method is used heat specific parts of the body (called “therapy points”) by using glowing sticks made of mugwort (“Moxa”) or heated needles that are put close to the therapy points.

-

Massages – Various massage techniques are used to relax muscles and ease tension.

-

Heating and cooling – This includes the use of hot packs and plasters, a hot bath, going to the sauna, or using an infrared lamp. Heat can also help relax tense muscles. Cold packs, like cold wraps or gel packs, are also used to help with irritated nerves.

-

Ultrasound therapy – Here the lower back is treated with sound waves. The small vibrations that are produced generate heat to relax body tissue.

-

Cervical Manipulation – There is limited evidence suggesting that cervical manipulation may provide short-term benefits for neck pain and cervicogenic headaches. Complications from manipulation are rare and can include worsening radiculopathy, myelopathy, spinal cord injury, and vertebral artery injury. These complications occur ranging from 5 to 10 per 10 million manipulations.

-

Lumbar Corset or Collar for Immobilization – In patients with acute neck pain, a short course (approximately one week) of collar immobilization may be beneficial during the acute inflammatory period.

- Traction – May be beneficial in reducing the radicular symptoms associated with disc herniations. Theoretically, traction would widen the neuroforamen and relieve the stress placed on the affected nerve, which, in turn, would result in the improvement of symptoms. This therapy involves placing approximately 8 to 12 lbs of traction at an angle of approximately 24 degrees of neck flexion over a period of 15 to 20 minutes.

Physical Therapy

- Exercising in water – can be a great way to stay physically active when other forms of exercise are painful. Exercises that involve lots of twisting and bending may or may not benefit you. Your physical therapist will design an individualized exercise program to meet your specific needs.

- Weight-training exercises – though very important, need to be done with proper form to avoid stress to the back and neck.

- Reduce pain and other symptoms – Your physical therapist will help you understand how to avoid or modify the activities that caused the injury, so healing can begin. Your physical therapist may use different types of treatments and technologies to control and reduce your pain and symptoms.

- Improve posture –If your physical therapist finds that poor posture has contributed to your herniated disc, the therapist will teach you how to improve your posture so that pressure is reduced in the injured area, and healing can begin and progress as rapidly as possible.

- Improve motion – Your physical therapist will choose specific activities and treatments to help restore normal movement in any stiff joints. These might begin with “passive” motions that the physical therapist performs for you to move your spine, and progress to “active” exercises and stretches that you do yourself. You can perform these motions at home and in your workplace to help hasten healing and pain relief.

- Improve flexibility – Your physical therapist will determine if any of the involved muscles are tight, start helping you to stretch them, and teach you how to stretch them at home.

- Improve strength – If your physical therapist finds any weak or injured muscles, your physical therapist will choose, and teach you, the correct exercises to steadily restore your strength and agility. For neck and back disc herniations, “core strengthening” is commonly used to restore the strength and coordination of muscles around your back, hips, abdomen, and pelvis.

- Improve endurance – Restoring muscular endurance is important after an injury. Your physical therapist will develop a program of activities to help you regain the endurance you had before the injury, and improve it.

- Learn a home program – Your physical therapist will teach you strengthening, stretching, and pain-reduction exercises to perform at home. These exercises will be specific for your needs; if you do them as prescribed by your physical therapist, you can speed your recovery.

Eat Nutritiously During Your Recovery

- All bones and tissues in the body need certain nutrients in order to heal properly and in a timely manner. Eating a nutritious and balanced diet that includes lots of minerals and vitamins are proven to help heal broken bones of all types. Therefore focus on eating lots of fresh produce (fruits and veggies), whole grains, lean meats, and fish to give your body the building blocks needed to properly repair your. In addition, drink plenty of purified water, milk, and other dairy-based beverages to augment what you eat.

- Broken bones need ample minerals (calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, boron) and protein to become strong and healthy again.

- Excellent sources of minerals/protein include dairy products, tofu, beans, broccoli, nuts and seeds, sardines, and salmon.

- Important vitamins that are needed for bone healing include vitamin C (needed to make collagen), vitamin D (crucial for mineral absorption), and vitamin K (binds calcium to bones and triggers collagen formation).

- Conversely, don’t consume food or drink that is known to impair bone/tissue healing, such as alcoholic beverages, sodas, most fast food items, and foods made with lots of refined sugars and preservatives.

Medication

Pharmacotherapy – There is no evidence to demonstrate the efficacy of non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) in the treatment of cervical radiculopathy. However, they are commonly used and can be beneficial for some patients. The use of COX-1 versus COX-2 inhibitors does not alter the analgesic effect, but there may be decreased gastrointestinal toxicity with the use of COX-2 inhibitors. Clinicians can consider steroidal anti-inflammatories (typically in the form of prednisone) in severe acute pain for a short period. A typical regimen is prednisone 60 to 80 mg/day for five days, which can then be slowly tapered off over the following 5 m to 14 days. Another regimen involves a prepackaged tapered dose of Methylprednisolone that tapers from 24 mg to 0 mg over 7 days.

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) – These painkillers belong to the same group of drugs as acetylsalicylic acid (ASA, the drug in medicines like “Aspirin”). NSAIDs that may be an option for the treatment of sciatica include diclofenac, ibuprofen, and naproxen. Anti-inflammatory drugs are drugs that reduce inflammation. This includes substances produced by the body itself like cortisone. It also includes artificial substances like ASA – acetylsalicylic acid (or “aspirin”) or ibuprofen –, which relieve pain and reduce fever as well as reducing inflammation.

-

Acetaminophen (paracetamol) – Acetaminophen (paracetamol) is also a painkiller, but it is not an NSAID. It is well tolerated and can be used as an alternative to NSAIDs – especially for people who do not tolerate NSAID painkillers because of things like stomach problems or asthma. But higher doses of acetaminophen can cause liver and kidney damage. The package insert advises adults not to take more than 4 grams (4000 mg) per day. This is the amount in, for example, 8 tablets containing 500 milligrams each. It is not only important to take the right dose, but also to wait long enough between doses.

-

Opioids – Strong painkillers that may only be used under medical supervision. Opioids are available in many different strengths, and some are available in the form of a patch. Morphine, for example, is a very strong drug, while tramadol is a weaker opioid. These drugs may have a number of different side effects, some of which are serious. They range from nausea, vomiting and constipation to dizziness, breathing problems, and blood pressure fluctuation. Taking these drugs for a long time can lead to habitual use and physical dependence.

- Skeletal Muscle relaxant – If muscle spasms are prominent, the addition of a muscle relaxant may merit consideration for a short period. For example, cyclobenzaprine is an option at a dose of 5 mg taken orally three times daily. Antidepressants (amitriptyline) and anticonvulsants (gabapentin and pregabalin) have been used to treat neuropathic pain, and they can provide a moderate analgesic effect.

-

Steroids – Anti-inflammatory drugs that can be used to treat various diseases systemically. That means that they are taken as tablets or injected. The drug spreads throughout the entire body to soothe inflammation and relieve pain. Steroids may increase the risk of gastric ulcers, osteoporosis, infections, skin problems, glaucoma, and glucose metabolism disorders.

-

Muscle relaxants – Sedatives which also relax the muscles. Like other psychotropic medications, they can cause fatigue and drowsiness, and affect your ability to drive. Muscle relaxants can also affect liver functions and cause gastro-intestinal complications. Drugs from the benzodiazepine group, such as tetrazepam, can lead to dependency if they are taken for longer than two weeks.

- Nerve Relaxant and Neuropathic Agents – Drugs(pregabalin & gabapentin) or Vitamin B1 B6, B12 and mecobalamin that address neuropathic—or nerve-related pain remover. This includes burning, numbness, and tingling.

-

Anticonvulsants – These medications are typically used to treat epilepsy, but some are approved for treating nerve pain (neuralgia). Their side effects include drowsiness and fatigue. This can affect your ability to drive.

- Antidepressants – These drugs are usually used for treating depression. Some of them are also approved for the treatment of pain. Possible side effects include nausea, dry mouth, low blood pressure, irregular heartbeat, and fatigue.

- Topical Medications – These prescription-strength creams, gels, ointments, patches, and sprays help relieve pain and inflammation through the skin.

- Calcium & vitamin D3 – to improve bone health and healing fracture. As a general rule, men and women age 50 and older should consume 1,200 milligrams of calcium a day, and 600 international units of vitamin D a day.

- Glucosamine & Diacerein, Chondroitin sulfate – can be used to tightening the loose tension, cartilage, ligament, and cartilage, ligament regenerate cartilage or inhabit the further degeneration of cartilage, ligament

- Injections near the spine – Injection therapy uses mostly local anesthetics and/or anti-inflammatory medications like corticosteroids (for example cortisone). These drugs are injected into the area immediately surrounding the affected nerve root. There are different ways of doing this:

-

In lumbar spinal nerve analgesia (LSPA) – the medication is injected directly at the point where the nerve root exits the spinal canal. This has a numbing effect on the nerve root.

-

In lumbar epidural analgesia – the medication is injected into what is known as the epidural space (“epidural injection”). The epidural space surrounds the spinal cord and the spinal fluid in the spinal canal. This is also where the nerve roots are located. During this treatment, the spine is monitored using computer tomography or X-rays to make sure that the injection is placed at exactly the right spot.

-

Interventional Treatments – Spinal steroid injections are a common alternative to surgery. Perineural injections (translaminar and transforaminal epidurals, selective nerve root blocks) are an option with pathological confirmation by MRI. These procedures should take place under radiologic guidance.[15]

-

Surgical Treatments

- Total Disc Replacement (TDR) and Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion (ACDF) – Surgical exposure of the desired vertebral level is achieved through an anterior cervical incision. Subcutaneous dissection is performed to allow for adequate mobilization to tissue incision. The discectomy is performed with pituitary rongeurs, a curette, and a burr drill to remove affected disc. The posterior longitudinal ligament can be left in situ depending on the severity of the herniation.

- Laminectomy – Cervical laminectomy removes the lamina on one or both sides to increase the axial space available for the spinal cord. Clinically indicated for spinal stenosis or cervical disc disease involving more than three levels of disc degeneration with anterior spinal cord compression. Single-level cervical disc herniation is usually managed with the anterior approach. The complications of the posterior approach include instability resulting in kyphosis, recalcitrant myofascial pain, and occipital headaches.

- Laminoplasty – The kyphotic deformity is a well-known complication of laminectomy. To preserve the posterior wall of the spinal canal while decompressing the spinal canal a Z-plasty technique for the lamina was developed. The variant of the procedure uses a hinged door for the lamina. Laminoplasty is commonly indicated for multilevel spondylotic myelopathy. Nerve root injury is seen in about 11% of the surgeries. This complication is unique to laminoplasty, and the suggested etiology is traction on the nerve root with the posterior migration of the spinal cord.[rx]

- Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion – A procedure that reaches the cervical spine (neck) through a small incision in the front of the neck. The intervertebral disc is removed and replaced with a small plug of bone or another graft substitute, and in time, that will fuse the vertebrae.

- Cervical corpectomy – A procedure that removes a portion of the vertebra and adjacent intervertebral discs to allow for decompression of the cervical spinal cord and spinal nerves. A bone graft, and in some cases a metal plate and screws, are used to stabilize the spine.

- Dynamic Stabilisation – Following a discectomy, a stabilization implant is implanted with a ‘dynamic’ component. This can be with the use of Pedicle screws (such as Dynesys or a flexible rod) or an interspinous spacer with bands (such as a Wallis ligament). These devices offload pressure from the disc by rerouting pressure through the posterior part of the spinal column. Like a fusion, these implants allow maintaining mobility to the segment by allowing flexion and extension.

- Facetectomy – A procedure that removes a part of the facet to increase the space.

- Foraminotomy – A procedure that enlarges the vertebral foramen to increase the size of the nerve pathway. This surgery can be done alone or with a laminotomy.

- Intervertebral disc annuloplasty (IDET) – A procedure wherein the disc is heated to 90 °C for 15 minutes in an effort to seal the disc and perhaps deaden nerves irritated by the degeneration.

- Intervertebral disc arthroplasty – also called Artificial Disc Replacement (ADR), or Total Disc Replacement (TDR), is a type of arthroplasty. It is a surgical procedure in which degenerated intervertebral discs in the spinal column are replaced with artificial ones in the lumbar (lower) or cervical (upper) spine.

- Laminoplasty – A procedure that reaches the cervical spine from the back of the neck. The spinal canal is then reconstructed to make more room for the spinal cord.

- Laminotomy – A procedure that removes only a small portion of the lamina to relieve pressure on the nerve roots.

- Microdiscectomy – A minimally invasive surgical procedure in which a portion of a herniated nucleus pulposus is removed by way of a surgical instrument or laser while using an operating microscope or loupe for magnification.

- Percutaneous disc decompression – A procedure that reduces or eliminates a small portion of the bulging disc through a needle inserted into the disc, minimally invasive.

- Spinal decompression – A non-invasive procedure that temporarily (a few hours) enlarges the intervertebral foramen (IVF) by aiding in the rehydration of the spinal discs.

- Spinal laminectomy – A procedure for treating spinal stenosis by relieving pressure on the spinal cord. A part of the lamina is removed or trimmed to widen the spinal canal and create more space for the spinal nerves.

Rehabilitation

Physical Therapy Management

Physical therapy often plays a major role in herniated disc recovery. Involving below key points

- Ambulation and resumption of exercise

- Pain control

- Education re maintaining a healthy weight

Physical therapy programs are often recommended for the treatment of pain and restoration of functional and neurological deficits associated with symptomatic disc herniation.

Active exercise therapy is preferred to passive modalities.

There are a number of exercise programs for the treatment of symptomatic disc herniation eg

- aerobic activity (eg, walking, cycling)

- directional preference (McKenzie approach)

- flexibility exercises (eg, yoga and stretching)

- proprioception/coordination/balance (medicine ball and wobble/tilt board),

- strengthening exercises.

- motor control exercises MCEs

MCEs (stabilization/core stability exercises) are a common type of therapeutic exercise prescribed for patients with symptomatic disc herniation[rx].

- designed to re-educate the co-activation pattern of abdominals, paraspinal, gluteals, pelvic floor musculature and diaphragm

- The biological rationale for MCEs is primarily based on the idea that the stability and control of the spine are altered in patients with LBP.

- the program begins with the recognition of the natural position of the spine (mid-range between lumbar flexion and extension range of motion), considered to be the position of balance and power for improving performance in various sports

- Initial low-level sustained isometric contraction of trunk-stabilizing musculature and their progressive integration into functional tasks is the requirement of MCEs

- MCE is usually delivered in 1:1 supervised treatment sessions and sometimes includes palpation, ultrasound imaging and/or the use of pressure biofeedback units to provide feedback on the activation of trunk musculature

- A core stability program decreases pain level, improves functional status, increases the health-related quality of life, and static endurance of trunk muscles in lumbar disc herniation patients[rx]. Individual high-quality trials found moderate evidence that stabilization exercises are more effective than no treatment[r].

Different studies have shown that a combination of different techniques will form the optimal treatment for a herniated disc. Exercise and ergonomic programs should be considered as very important components of this combined therapy[24].

Physiotherapy Modalities and the evidence for their use in disc herniation

- Stretching – There is low-quality evidence found to suggest that adding hyperextension to an intensive exercise program might not be more effective than intensive exercise alone for functional status or pain outcomes. There were also no clinically relevant or statistically significant differences found in disability and pain between combined strength training and stretching, and strength training alone[rx].

- Muscle Strengthening – Strong muscles are a great support system for your spine and better handle pain. If core stability is totally regained and fully under control, strength and power can be trained. But only when this is necessary for the patient’s functioning/activities. This power needs to be avoided during the core stability exercises because of the combination of its two components: force and velocity. This combination forms a higher risk to gain back problems and back pain[rx].

- Traditional Chinese Medicine for Low Back Pain – has been demonstrated to be effective. Reviews have demonstrated that acupressure, acupuncture, and cupping can be efficacious in pain and disability for chronic low back pain included disc herniation[rx][rx].

- Spinal Manipulative Therapy and Mobilization – Spinal manipulative therapy and mobilization lead to short-term pain relief when suffering from acute low back pain. When looking at chronic low back pain, manipulation has an effect similar to NSAID[rx].

- Behavioural Graded Activity Programme – A global perceived recovery was better after a standard physiotherapy program than after a behavioral graded activity program in the short term, however, no differences were noted in the long term[rx].

- Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) – TENS therapy contributes to pain relief and improvement of function and mobility of the lumbosacral spine[rx].

- Manipulative Treatment – Manipulative treatment on lumbar disc herniation appears to be safe, effective, and it seems to be better than other therapies. However high-quality evidence is needed to be further investigated[rx].

- Traction – A recent study has shown that traction therapy has positive effects on pain, disability, and SLR on patients with intervertebral disc herniation[rx]. Also, one trial found some additional benefit from adding mechanical traction to medication and electrotherapy[rx].

- Aquatic Vertical Traction – In patients with low back pain and signs of nerve root compression this method had greater effects on spinal height, the relieving of pain, lowering the centralization response, and lowering the intensity of pain than the assuming of a supine flexing position on land[rx].

- Hot Therapies – may use heat to increase blood flow to the target area. Blood helps heal the area by delivering extra oxygen and nutrients. Blood also removes waste byproducts from muscle spasms.

Example of Protocol for Rehabilitation Following a Lumbar Microdiscectomy

The following program is an example of a protocol for rehabilitation following a lumbar microdiscectomy

- Duration of rehabilitation program: 4 weeks

- Frequency – every day

- Duration of one session – approximately 60 minutes

- Treatment – dynamic lumbar stabilization exercises + home exercises

- Exercises – Prior to the DLS training session patients are provided with instruction or technique to ensure and protect a neutral spine position. During the first 15 minutes of each session stretching of back extensors, hip flexors, hamstrings and Achilles tendon should be performed.

- DLS consists of – Quadratus exercises Abdominal strengthening Bridging with ball Straightening of external abdominal oblique muscle Lifting one leg in crawling position Lifting crossed arms and legs in crawling position Lunges)

- Home Exercises – should be added to the treatment. These should be performed every day. 5 repetitions during the first week up to 10-15 reps in the following weeks

Post Surgical Intervention – In the case of surgery, programs start regularly 4-6 weeks post-surgery

- Offer information about the rehabilitation program they will follow the next few weeks.

- The patients are instructed and accompanied in daily activities such as: coming out of bed, going to the bathroom and clothing

- Patients have to pay attention on the ergonomics of the back throughout back school[rx][rx][rx][rx].

Studies show various forms of post-operation treatment show

- Rehabilitation programs that start four to six weeks post-surgery with exercises versus no treatment found that exercise programs are more effective than no treatment in terms of short-term follow-up for pain

- High-intensity exercise programs are slightly more effective for pain and in terms of functional status in the short term compared with low-intensity exercise programs.

- Long-term follow-up results for both pain and functional status showed no significant differences between groups.

- No significant differences between supervised exercise programs and home exercise programs in terms of short-term pain relief[rx].

Complications of Intervertebral Disc Herniation

Complications from steroid injections are typically mild and range between 3% to 35% of cases. Other, more serious complications can include[rx]

-

Nerve injury

-

Infection

-

Epidural hematoma

-

Epidural abscess

-

Spinal cord infarction

-

Bleeding

-

Recurrence of disease or symptoms

-

Infection

-

Worsening neurological deficits

-

Failed operation

Complications from surgical intervention include[rx]

-

Infection

-

Recurrent laryngeal, superior laryngeal, and hypoglossal nerve injuries

-

Esophageal injury

-

Vertebral and carotid injuries

-

Dysphagia

-

Horner syndrome

-

Pseudoarthrosis

-

Adjacent segment degeneration

A team approach is an ideal way to limit the complications of such an injury

-

Evaluation of a patient with lumbar radicular pain by the primary care provider to rule out severe radiculopathy or alarm symptoms is the recommended first step.

-

Conservative management should commence when symptoms are mild or moderate; including moderate activity, stretches, and pharmacological management. A pharmacist should evaluate dosing and perform medication reconciliation to preclude any drug-drug interactions, and alert the healthcare team regarding any concerns.

-

The patient should follow up with primary care physicians one to two weeks following initial injury to monitor for progression of the nerve damage.

-

If symptoms worsen on follow up or there is a concern for the development of a severe radiculopathy referral to neurosurgery or hospitalization for possible spinal decompression.

-

If radicular symptoms persist three weeks after injury, physical therapy referral can be a consideration.

-

When symptoms persist for greater than six-week duration, imaging such as MRI or CT can are options for better visualization of the nerve roots.

-

The patient should consult with a dietitian and eat a healthy diet and maintain a healthy weight.

-

The pharmacist should encourage the patient to quit smoking, as this may help with the healing process. Further, the pharmacist should educate the patient on pain management and available options.

-

Persistent pain at six weeks follows up may warrant a referral to interventional pain management or neurosurgery for an epidural steroid injection.

-

If mild to moderate symptoms continue at three months following the onset of symptoms, referral for possible surgical intervention merits consideration as well.

Prevention

To prevent experiencing a herniated disc, individuals should:

- Use proper body mechanics when lifting, pushing, pulling, or performing any action that puts extra stress on your spine.

- Maintain a healthy weight. This will reduce the stress on your spine.

- Stop smoking.

- Discuss your occupation with a physical therapist, who can provide an analysis of your job tasks and offer suggestions for reducing your risk of injury.

- Keep your muscles strong and flexible. Participate in a consistent program of physical activity to maintain a healthy fitness level.

Many physical therapy clinics offer “back schools,” which teach people how to take care of their backs and necks and prevent injury. Ask your physical therapist about programs in your area. If you don’t have a physical therapist.

To prevent recurrence of a herniated disc, follow the above advice, and:

- Continue the new posture and movement habits that you learned from your physical therapist, to keep your back healthy.

- Continue to do the home-exercise program your physical therapist taught you, to help maintain your improvements.

- Continue to be physically active and stay fit.

You Can Prevent Lumbar Disc Herniation By Exercise Regular With This Machine

References