Ulnar Nerve Paralysis/Ulnar Nerve Palsy can result in loss of sensory and motor function. This can occur after injury to any portion of the ulnar nerve. The ulnar nerve is the terminal branch of the medial cord (C8, T1). The ulnar nerve innervates the flexor carpi ulnaris after it passes through the cubital tunnel.[rx][rx][rx][rx]

Ulnar nerve entrapment is a condition where the ulnar nerve becomes physically trapped or pinched, resulting in pain, numbness, or weakness, primarily affecting the little finger and ring finger of the hand. Entrapment may occur at any point from the spine at cervical vertebra C7 to the wrist; the most common point of entrapment is in the elbow (Cubital tunnel syndrome). Prevention is mostly through correct posture and avoiding repetitive or constant strain (e.g. cell phone elbow). Treatment is usually conservative, including medication, activity modification and exercise, but may sometimes include surgery. Prognosis is generally good, with mild to moderate symptoms often resolving spontaneously.

The nerve provides sensation over the medial half of the 4th finger and the entire 5th finger and the ulnar portion of the dorsal aspect of the hand.

Other muscles innervated by the ulnar nerve are the flexor digitorum profundus of the ring and small fingers and the following hand muscles:

-

Abductor digiti minimi

-

Flexor digiti minimi

-

Opponens digiti minimi

-

Ring

-

Small finger lumbricals

-

Dorsal and palmar interosseous muscles

-

Adductor pollicis

-

Deep head of flexor pollicis brevis

-

The first dorsal interosseous

When the ulnar nerve is injured, the muscles innervated by the nerve begin to weaken. This leads to an imbalance between the strong extrinsic muscles (i.e., extensor digitorum communis) and the weakened intrinsic muscles (i.e., interossei and lumbricals). This imbalance is characterized clinically by metacarpophalangeal (MCP) hyperextension and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) and distal interphalangeal (DIP) flexion. After carpal tunnel syndrome, entrapment of the ulnar nerve is the second most common neuropathy of the upper extremity.

The ulnar nerve can be entrapped at several sites that include the following:

-

At the elbow (cubital tunnel)- the most common

-

Epicondylar region (ulnar groove)-the second most common site near the wrist

-

Entrapment can also occur anywhere between the elbow and the wrist

Anatomy of Ulnar Nerve Paralysis

Pathoanatomic components relate to the imbalance between the extrinsic and intrinsic muscles. Weakened intrinsic muscles lead to a loss of MCP flexion and a loss of interphalangeal (IP) extension. Strong extrinsic muscles will lead to an unopposed extension of the MCP joints. The flexor digitorum profundus and flexor digitorum superficialis muscles not innervated by the ulnar nerve remain strong and lead to unopposed flexion of the PIP and DIP joints.

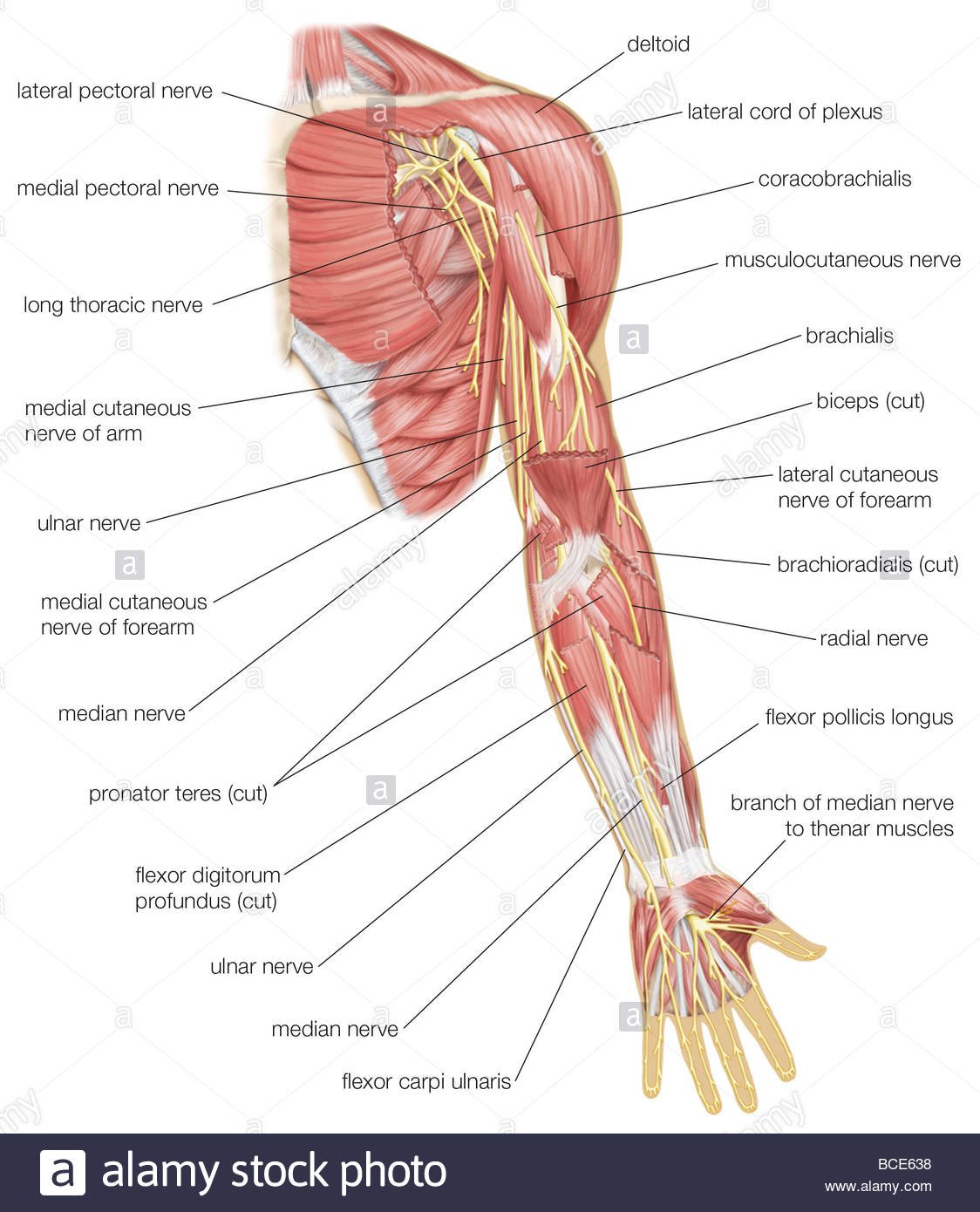

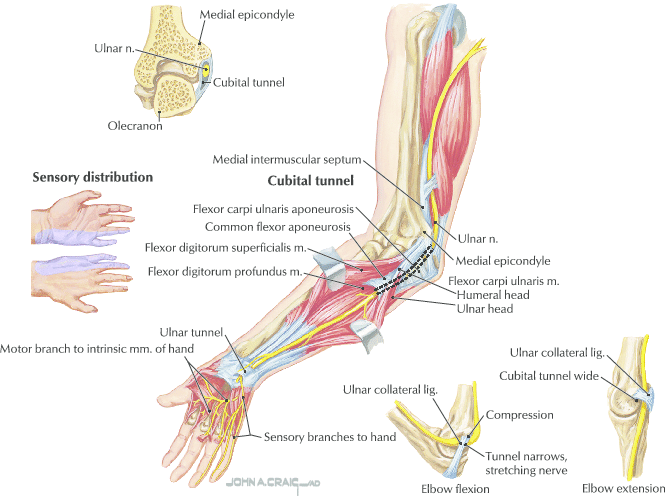

C8 and T1 nerve roots join and give rise to the medial cord of the brachial plexus. Ulnar nerve originates as a branch of the medial cord. The ulnar nerve then travels down the arm along with the brachial artery towards the elbow joint. At the midpoint of the arm, the nerve enters the posterior compartment by piercing the intermuscular septum(arcade of Struthers). It then traverses along the medial aspect of the triceps to enter the cubital tunnel. At this point, the ulnar nerve travels between the olecranon and the medial epicondyle and beneath the Osborne ligament. Once the nerve exits the cubital tunnel, it passes under the aponeurotic head of flexor carpi ulnaris to enter the forearm. The cubital tunnel region is where the ulnar nerve is most likely to be compressed due to its location and anatomy. However, the nerve can also get compressed at the arcade of Struthers or by the aponeurotic head of flexor carpi ulnaris resulting in symptoms of ulnar neuropathy. The ulnar nerve innervates the medial side of the forearm, ulnar side of the palm, the little finger and ulnar half of the ring finger. It supplies motor branches to flexor carpi ulnaris, flexor profundus of the little and ring fingers, hypothenar muscles, adductor pollicis brevis, all of the interossei and the third and fourth lumbricals. It is noteworthy that the ulnar nerve gives no motor or sensory branches above the elbow.

Causes of Ulnar Nerve Paralysis

Causes of claw hand can also be due to anything that may lead to ulnar nerve palsy. Ulnar nerve palsy can arise from a laceration anywhere along its course. Proximal injuries to the medial cord of the brachial plexus may also present with sensory loss distally. Ulnar nerve palsies can also be due to cubital tunnel syndrome and ulnar tunnel syndrome. These are compression neuropathies at the elbow and wrist. Another cause of ulnar nerve palsy may be due to a failure to splint the hand in an intrinsic-plus posture following a crush injury. There are a few systemic diseases which may also lead to ulnar nerve palsy. These include leprosy, syringomyelia, and Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. However, these systemic diseases usually involve more than one nerve.[rx][rx]

When a claw hand results, it is usually due to paralysis of the lumbricals.

Multiple etiologies can result in ulnar nerve compression at the cubital tunnel and cause symptoms such as tingling along the medial aspect of the forearm, the little finger, and medial aspect of the ring finger.

-

Pressure – on the ulnar nerve is a common cause of symptoms. The ulnar nerve is quite superficial at the point of the medial epicondyle; this is why people may experience the feeling of shooting pain and electric shock in the forearm if they accidentally hit their elbow on a hard surface.

-

Stretching – the ulnar nerve can also result in similar symptoms. The ulnar nerve lies behind the medial epicondyle. During flexion of the elbow joint, the ulnar nerve gets stretched because of this anatomical position. Repetitive elbow flexion and extension can cause further damage and irritation to the ulnar nerve. Some individuals sleep with elbows bent which can stretch the ulnar nerve for an extended period during sleep, which is an identified cause of irritation to the ulnar nerve.

-

Injuries – to the elbow joint (fractures, dislocations, swelling, effusions) can cause anatomical damage which will cause symptoms because of compression/irritation of the ulnar nerve.

- Problems originating at the neck – thoracic outlet syndrome, cervical spine pathology, compression by anterior scalene muscles

- Problems originating in the chest – compression by pectoralis minor muscles

- Brachial plexus abnormalities – It is the most common causes of ulnar nerve root compression and radiating pain’

- Artery aneurysms or thrombosis – That causes of abnormality of blood flow.

- Elbow – fractures, growth plate injuries, cubital tunnel syndrome, flexor-pronator aponeurosis, the arcade of Struthers[rx]

- Forearm – tight flexor carpi ulnaris muscles[rx]

- Wrist – fractures, ulnar tunnel syndrome, hypothenar hammer syndrome

- Other – Infections, tumors, diabetes, hypothyroidism, rheumatism, and alcoholism

- the ulnar nerve slipping out of place when the elbow is bent

- Fluid buildup in the elbow

- Current or previous injury to the inside of the elbow

- Bone spurs in the elbow

- Arthritis in the elbow or wrist

- Swelling in the elbow or wrist joint

- An activity that causes a person to bend and straighten the elbow joint repeatedly

Symptoms of Ulnar Nerve Paralysis

Cubital tunnel syndrome can cause an aching pain on the inside of the elbow. Most of the symptoms, however, occur in your hand.

- Numbness and tingling – in the ring finger and little finger are common symptoms of ulnar nerve entrapment. Often, these symptoms come and go. They happen more often when the elbow is bent, such as when driving or holding the phone. Some people wake up at night because their fingers are numb.

- The feeling of “falling asleep” – in the ring finger and little finger, especially when your elbow is bent. In some cases, it may be harder to move your fingers in and out, or to manipulate objects.

- The weakening of the grip – and difficulty with finger coordination (such as typing or playing an instrument) may occur. These symptoms are usually seen in more severe cases of nerve compression.

- If the nerve is very compressed – or has been compressed for a long time, muscle wasting in the hand can occur. Once this happens, muscle wasting cannot be reversed. For this reason, it is important to see your doctor if symptoms are severe or if they are less severe but have been present for more than 6 weeks.

- Primarily the hypothenar muscles – and interossei with muscle-sparing of the thenar group:

- weakened finger abduction and adduction (interossei)

- weakened thumb adductor (adductor pollicis)

- Sensory loss – and pain which may involve the palmar surface of the fifth digit and medial aspect of the fourth digit & the dorsum of medial aspect of the fourth finger and the dorsum of the fifth finger don’t have sensory loss.

- Ulnar Claw – may present (a sign of Benediction)

- Intermittent numbness and tingling in the ring and pinkie fingers

- A weak grip in the affected hand

- A feeling of the pinkie and ring fingers “falling asleep”

- Difficulty controlling fingers for precise tasks, such as typing or playing an instrument

- Sensitivity to cold temperatures

- Pain or tenderness in the elbow joint, especially along the inner aspect

Stage

Grade I: Mild symptoms including:

- Intermittent paresthesia

- Minor hypoesthesia of the dorsal and palmar surfaces of the fifth and medial aspect of fourth digits

- No motor changes

Grade II: Moderate and persistent symptoms including:

- Paresthesia

- Hypoesthesia of the dorsal and palmar surfaces of the fifth and medial aspect of fourth digits

- Mild weakness of ulnar innervated muscles

- Early signs of muscular atrophy

Grade III: Severe symptoms including:

- Paresthesia

- Obvious loss of sensation of the dorsal and palmar surfaces of the fifth and medial aspect of fourth digits.

- Significant functional and motor impairment

- Muscle atrophy of the hand intrinsics

- Possible digital clawing of fourth and fifth digits (Sign of Benediction)

Diagnosis of Ulnar Nerve Paralysis

History and Physical

The initial presentation will include a decrease in normal hand function.

- The MCP joints will be hyperextended, and the IP joints flexed. The second and third digits will not be as involved as the fourth and fifth digits with a true ulnar nerve palsy. This is because the median nerve innervates the lumbricals involving the second and third digits, and the ulnar nerve innervates the lumbricals involving the fourth and fifth digits. The patient may also exhibit functional weakness while attempting a grasp, grip, or pinch.

- A provocative test for claw hand is bringing the MCP joints into flexion. This will correct the DIP and PIP joint deformities.

Several other specific tests for ulnar nerve palsy include

-

Froment sign – Hyperflexion of the thumb IP joint while attempting to grab. This indicates a substitution of flexor pollicis longus (innervated by median nerve) for adductor pollicis (innervated by ulnar nerve).

-

Jeanne sign – Reciprocal hyperextension of the thumb MCP joint indicating substitution of flexor pollicis longus (FPL) for adductor pollicis.

-

Wartenberg sign – Abduction of the small finger at MCP joint indicating deficient palmar intrinsic muscle (innervated by ulnar nerve) with abduction from extensor digit minimi (innervated by the radial nerve).

- Duchenne sign – Clawing of the ring and small fingers, hyperextension of MCP joints and flexion of PIP joints indicating deficient interosseous and lumbrical muscles of the ring and small fingers.

- Tinel’s sign – at the cubital and ulnar tunnels may reproduce symptoms of paresthesias and numbness, indicating a likely compressive neuropathy at that location.

Imaging

- X-rays – X-rays of the affected extremity at the elbow and wrist should be obtained to rule out any osseous deformity that may cause nerve entrapment, as well as cervical spine radiographs that may reveal sources of radiculopathy or first rib involvement. Finally, a chest x-ray should be obtained to rule out compression of the medial chord by an apical lung or Pancoast tumor, particularly in a patient with a positive history for smoking.

- MRI – is an imaging modality that can be further used to confirm clinical suspicions of cervical radiculopathy in the neck, or of a ganglion or other space-occupying lesions in the wrist.

- Ultrasound – of the nerve at the elbow and wrist can be used to measure the size of the ulnar nerve compared to controls, as well as to identify a thrombosis of the ulnar artery that can lead to ulnar nerve symptoms originating in Guyon’s canal.[rx]

- Electromyography – is also commonly used in the diagnosis of compression neuropathy with muscle denervation. Compressive neuropathies result in increased distal latency and decreased conduction velocity. Thus in patients with cubital tunnel syndrome, one is likely to identify a slowing of conduction in the ulnar nerve segment crossing the elbow.[rx][rx]

- Both ultrasonic scanning (USS) – and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have sensitivity and specificity over 80% in diagnosis. MRI and USS are also helpful to identify other causes of compression, which may not be picked up on plain radiograph films such as soft tissue swelling and lesions such as neuroma, ganglions, aneurysms, etc.[rx]

- Electromyographic and nerve conduction velocity – studies are used to evaluate the ulnar nerve pathology and to rule out other diagnoses.[rx][rx]

![]()

Treatment of Ulnar Nerve Paralysis

Nonoperative management is applied if a fixed flexion contracture of more than 45 degrees occurs at the PIP joint. A strenuous hand therapy program is utilized involving serial casting.[rx][rx]

- Bracing or splinting – Your doctor may prescribe a padded brace or splint to wear at night to keep your elbow in a straight position.

- Nerve gliding exercises – Some doctors think that exercises to help the ulnar nerve slide through the cubital tunnel at the elbow and the Guyon’s canal at the wrist can improve symptoms. These exercises may also help prevent stiffness in the arm and wrist.

- Exercises – that strengthen the interosseous muscles and lubricants are recommended. The individual should be taught to exercise each finger and thumb in abduction and adduction motion while the hand is pronated. In addition, the MCP and ICP joints should be exercised and over time the interosseous and lumbrical will gain strength.

Medication

If the injury is severe and pain is intolerable the following medicine can be considered to prescribe

- NSAIDs – Prescription-strength drugs that reduce both pain and inflammation. Pain medicines and anti-inflammatory drugs help to relieve pain and stiffness, allowing for increased mobility and exercise. There are many common over-the-counter medicines called non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). They include and Ketorolac, Aceclofenac, Naproxen, Etoricoxib.

- Corticosteroids – Also known as oral steroids, these medications reduce inflammation.

- Muscle Relaxants – These medications provide relief from associated muscle spasms.

- Neuropathic Agents – Drugs(pregabalin & gabapentin) that address neuropathic—or nerve-related—pain. This includes burning, numbness, and tingling.

- Opioids – Also known as narcotics, these medications are intense pain relievers that should only be used under a doctor’s careful supervision.

- Topical Medications – These prescription-strength creams, gels, ointments, patches, and sprays help relieve pain and inflammation through the skin.

- Calcium & vitamin D3 – to improve bone health and healing fracture. As a general rule, men and women age 50 and older should consume 1,200 milligrams of calcium a day, and 600 international units of vitamin D a day.

- Antidepressants – A drug that blocks pain messages from your brain and boosts the effects of endorphins (your body’s natural painkillers).

- B1, B6, B12 – It help to erase the chronic radiating pain and work as a neuropathy agent.

- Intra-articular corticosteroid injections – may be useful for symptomatic injury especially where there is a considerable inflammatory component. The delivery of the corticosteroid directly. It may reduce local inflammation associated with injury and minimize the systemic effects of the steroid.

Surgery

Various methods of surgical treatment have been discussed and performed. Some of the well-accepted surgical procedures for the treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome are

- in-situ decompression;

- endoscopic decompression;

- decompression followed by subsequent subcutaneous transposition, intramuscular transposition, or submuscular transposition and

- medial epicondylectomy along with in-situ decompression.[rx] Studies have shown no benefit of one over the other in terms of clinical outcomes.[rx]

-

Surgery is usually in the form of tendon transfers. This addresses issues including the lack of thumb adduction and lateral pinch, the claw deformity of the fingers that impairs object acquisition, and the loss of ring and small finger flexion.

-

The extensor carpi radialis brevis or the flexor digitorum superficialis is the most commonly used transfers to restore thumb adduction. The brachioradialis can be used if the extensor carpi radialis brevis is required for an intrinsic reconstruction of the fingers.

-

To correct the claw deformity of the fingers include static procedures or dynamic transfers. A dynamic transfer uses the flexor digitorum superficialis, extensor carpi radialis longus, extensor carpi radialis brevis, or flexor carpi radialis as a donor’s muscle.

-

To restore the ring and small finger extrinsic muscle function, a transfer of flexor digitorum profundus ring and small to flexor digitorum profundus middle is performed.

Nerve transfer

- in the report by Özkan T, et al., prospective study was conducted to evaluate patient outcomes following sensory nerve transfer; 20 patients with irreparable ulnar or median nerve lesions underwent the procedure; 18 of 20 patients attended a sensory re-education program after surgery; 2-point discrimination of less than 10 mm was achieved in 15 of 25 hands; 18 of 20 patients reported that the function of their hands improved after the procedure good or excellent results were associated with immediate transfer of the nerve, young age, and patients’attendance to the sensory re-education program after surgery;

Nerve conduits

- may be indicated when a tension-free repair is not possible; may only allow 2 cm of nerve regeneration

Repair Based on Level of Injury nerve repair in the hand

more proximal lacerations have worse outcomes than distal lacerations; at the wrist level, one-half of patients will have good result; exam findings for nerve injury:

- loss of two-point discrimination dryness over the affected dermatomes (loss of sweat gland innervation)

Digital nerves

digital nerves may contain one to three fascicles;

- best managed w/ epineural nerve repair use 9-0 or 10-0 prolene; patients may expect functional/protective sensation, but in the majority of patients, the normal sensation will not be obtained; generally, nerve repair is not indicated distal to the DIP;

Median and ulnar nerves at the wrist

- low median lesions (median nerve injuries at the wrist) low ulnar lesion in these injuries, wrist flexion significantly reduces tension at the nerve repair site; elbow flexion and nerve transposition will have no effect on tension at the repair site; group fascicular nerve repair may be indicated for nerve lacerations at the wrist level;

Ulnar nerve lacerations at the elbow

- tension at nerve repair site may be reduced by both nerve transposition and elbow flexion, but magnitude of this effect remains unclear;

Nerve Repair Techniques

- note that whatever repair technique is used, the repair should be strong to withstand the need for early ROM should it be necessary (as in concomitant tendon injury); epineural nerve repair involves repair of the epineural tissue – the loose connective tissue which surrounds the fascicles; group fascicular nerve repair: involves repair of the internal epineural tissue which surrounds the group fascicles; disadvantages include the increased need for nerve manipulation in order to align fascicles and the possibility of anastomosing incorrect fascicles (which will lead to a poor result); management of tension at nerve site repair:

- indicated for nerve defects more than 1 cm (or in any case where the nerve would be repaired under tension);

sural nerve graft; note that the patient must be in the lateral position for nerve harvest, which may interfere with the positioning

Physical Therapy

- The impairment-based approach can be used to address deficits in strength, ROM, and the attainment of functional goals

- The source of the pain should be treated in conjunction with the impairments.

- Following treatment, reassess the functional task that produced pain to determine effective treatment outcome

- Administer a home exercise program that aims to treat the same impairments and function tasks In a study conducted by Svernlov and colleagues, three treatments were compared for individuals with cubital tunnel syndrome.[rx] All three groups had positive outcomes, with the control group improving just as much as the intervention groups.[rx]

- Splint group protocol – An elbow brace was worn every night for a period of three months and the brace prevented elbow flexion beyond 45 degrees.

- Nerve gliding protocol – Patients were instructed to complete nerve gliding exercises two times per day in six different positions and hold them for 30 seconds for three repetitions with a 1-minute break in between each repetition. Patients were instructed to complete these exercises until the next visit, which occurred 1-2 weeks later. The frequency of the exercises was increased to three times per day, holding the exercise for one minute each day for a period of three months if there were no symptoms at the next visit.

- Control group protocol – The control group only received education According to a case report by Coppieters and colleagues, joint mobilizations of the elbow, thoracic spine and rib thrust manipulations, and ulnar nerve sliding/tension techniques for six sessions were associated with improvements of decreased elbow pain and considerable improvement scores on a neck questionnaire up to a ten-month follow-up.[rx] The patient reported a history of symptoms for two months prior to starting physical therapy.[rx] The protocol used in this study can be seen by accessing the link in the case study section below.