Knee Osteoarthritis (OA), also known as degenerative joint disease, is typically the result of wear and tear and progressive loss of articular cartilage. It is most common in elderly women and men. Knee osteoarthritis can be divided into two types, primary and secondary. Primary osteoarthritis is articular degeneration without any apparent underlying reason. Secondary osteoarthritis is the consequence of either an abnormal concentration of force across the joint as with post-traumatic causes or abnormal articular cartilage, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Osteoarthritis is typically a progressive disease that may eventually lead to disability. The intensity of the clinical symptoms may vary from each individual.

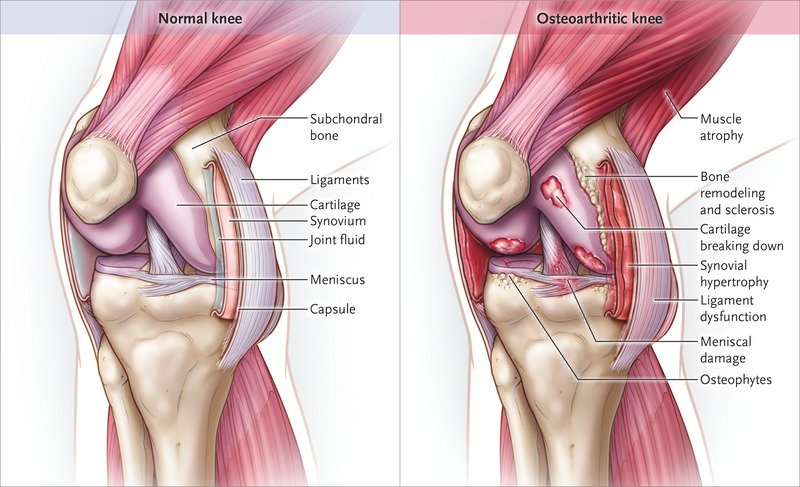

Osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee is a chronic, progressive joint disorder characterized by degeneration of articular cartilage, remodeling of subchondral bone, osteophyte formation, and synovial inflammation. It leads to pain, stiffness, reduced mobility, and functional impairment. Knee OA affects roughly 10% of men and 13% of women over age 60 worldwide, making it a leading cause of disability and reduced quality of life in older adults [rx]. Risk factors include age, obesity, joint injury, genetics, and biomechanical stress [rx].

Pathophysiologically, focal loss of cartilage integrity exposes subchondral bone, triggering aberrant repair responses: bone sclerosis, microfractures, and cysts. Inflammation from synovial cells and chondrocyte-derived cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α) perpetuates matrix degradation. Mechanotransduction pathways further exacerbate tissue breakdown under abnormal load, leading to pain and functional decline [rx].

Types of Knee Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis of the knee can be classified in several ways, reflecting etiology and anatomical distribution:

-

Primary (Idiopathic) OA

Primary OA arises without an identifiable cause, typically due to age-related cartilage degeneration and cumulative mechanical stress. Genetic predisposition influences cartilage resilience and matrix repair capacity, making some individuals more susceptible even in the absence of injury. -

Secondary OA

Secondary OA occurs following a specific insult or condition that damages cartilage. Common precipitating factors include prior traumatic injuries (e.g., ligament tears, fractures), metabolic disorders (e.g., hemochromatosis), endocrine imbalances (e.g., hyperparathyroidism), and inflammatory arthritides (e.g., gout). -

Unicompartmental vs. Tricompartmental OA

Depending on which compartment of the knee is affected, OA may be:-

Medial compartment OA, the most common pattern, often due to varus malalignment.

-

Lateral compartment OA, less common, associated with valgus alignment.

-

Patellofemoral OA, affecting the joint between the kneecap and femur, leading to anterior knee pain.

-

Tricompartmental OA, involving all three compartments and signifying advanced disease.

-

-

Rapidly Progressive OA

A subset characterized by swift joint space narrowing and subchondral bone collapse over months rather than years. Etiologies include abnormal biomechanical stresses, certain medications (e.g., corticosteroids), and metabolic factors.

Causes of Knee Osteoarthritis

Knee osteoarthritis is classified as either primary or secondary, depending on its cause. Primary knee osteoarthritis is the result of articular cartilage degeneration without any known reason. This is typically thought of as degeneration due to age as well as wear and tear. Secondary knee osteoarthritis is the result of articular cartilage degeneration due to a known reason.[rx][rx]

-

Age-Related Wear and Tear

With advancing age, chondrocyte function declines and cartilage matrix becomes less resilient, predisposing joints to degenerative changes. -

Obesity

Excess body weight increases mechanical load across the knee during activities, accelerating cartilage breakdown and subchondral bone remodeling. -

Previous Joint Injury

Traumatic events such as anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears or meniscal injuries disrupt joint stability and biomechanics, leading to early cartilage degeneration. -

Malalignment

Varus (bow-legged) or valgus (knock-knee) alignment concentrates stress on a single compartment, promoting unilateral cartilage wear. -

Repetitive Occupational/Mechanical Stress

Jobs or activities involving kneeling, squatting, or heavy lifting place chronic stress on knee cartilage and bone. -

Genetic Predisposition

Variations in genes encoding collagen type II, aggrecan, and other matrix components affect cartilage resilience and repair. -

Female Sex

Women, particularly postmenopausal, exhibit higher knee OA prevalence, likely due to hormonal influences on cartilage and bone metabolism. -

Hormonal Factors

Estrogen deficiency after menopause may impair cartilage homeostasis and subchondral bone quality. -

Metabolic Disorders

Conditions such as diabetes mellitus alter cartilage metabolism through glycation end-products, increasing stiffness and susceptibility to damage. -

Inflammatory Arthritides

Diseases like rheumatoid arthritis can lead to secondary OA by chronic synovial inflammation and proteolytic enzyme release. -

Hemochromatosis

Iron overload in joints catalyzes free radical formation, damaging cartilage matrix. -

Paget’s Disease of Bone

Abnormal bone remodeling beneath cartilage can compromise joint congruity and shock absorption. -

Joint Dysplasia

Developmental malformations in hip or knee morphology alter load distribution, predisposing to early degeneration. -

Neuromuscular Diseases

Muscle weakness or paralysis (e.g., polio) causes abnormal joint loading and cartilage wear. -

Charcot Arthropathy

Loss of protective sensation in joints (e.g., diabetic neuropathy) leads to unrecognized microtrauma and progressive OA. -

Crystal Deposition

Deposition of calcium pyrophosphate or urate crystals in cartilage triggers inflammation and mechanical damage. -

Obesity-Related Inflammation

Adipokines from visceral fat promote systemic low-grade inflammation, contributing to cartilage catabolism. -

Ligamentous Laxity

Chronic joint instability increases shear forces across cartilage surfaces. -

High-Impact Sports

Activities like soccer or basketball subject the knee to repeated impact and pivoting, increasing injury risk and subsequent OA. -

Smoking

Nicotine and other toxins impair blood flow to subchondral bone and alter chondrocyte metabolism, reducing cartilage repair.

Possible Causes of Secondary Knee OA

-

Posttraumatic

-

Postsurgical

-

Congenital or malformation of the limb

-

Malposition (Varus/Valgus)

-

Scoliosis

-

Rickets

-

Hemochromatosis

-

Chondrocalcinosis

-

Ochronosis

-

Wilson disease

-

Gout

-

Pseudogout

-

Acromegaly

-

Avascular necrosis

-

Rheumatoid arthritis

-

Infectious arthritis

-

Psoriatic arthritis

-

Hemophilia

-

Paget disease

-

Sickle cell disease

Risk Factors for Knee OA

Modifiable

-

Articular trauma

-

Occupation – prolonged standing and repetitive knee bending

-

Muscle weakness or imbalance

-

Weight

-

Health – metabolic syndrome

Non-modifiable

-

Gender – females more common than males

-

Age

-

Genetics

-

Race

Cartilage Changes in Aging[rx]

-

Water content – decreased

-

Collagen – same

-

Proteoglycan content – decreased

-

Proteoglycan synthesis – same

-

Chondrocyte size – increased

-

Chondrocyte number – decreased

-

Modulus of elasticity – increased

Cartilage Changes in OA

-

Water content – increased

-

Collagen – disorganized

-

Proteoglycan content – decreased

-

Proteoglycan synthesis – increased

-

Chondrocyte size – same

-

Chondrocyte number – same

-

Modulus of elasticity – decreased

Matrix Metalloproteases

Responsible for cartilage matrix degradation

-

Stromelysin

-

Plasmin

-

Aggrecanase-1 (ADAMTS-4)

-

Collagenase

-

Gelatinase

Tissue inhibitors of MMPs

Control MMP activity preventing excess degradation

-

TIMP-1

-

TIMP-2

-

Alpha-2-macroglobulin

The Symptom Of Osteoarthritis (OA) Of Knee

- Pain (particularly when you’re moving your knee or at the end of the day – this usually gets better when you rest)

- Stiffness (especially after rest – this usually eases after a minute or so as you get moving)

- Crepitus, a creaking – crunching, grinding sensation when you move the joint

- Hard swellings – (caused by osteophytes)

- Soft swellings – (caused by extra fluid in the joint).

- Loss of flexibility – You may not be able to move your joint through its full range of motion.

- Grating sensation – You may hear or feel a grating sensation when you use the joint.

- Bone spurs – These extra bits of bone, which feel like hard lumps, may form around the affected joint.

- Instability of the knee joint, or feeling like your knee joint is “giving way”

- Limitations in the range of movement of your knee

- Inability to continue with activities, whether they involve day-to-day tasks or sports

- Feeling the kneecap shift or slide out of the groove

- Feeling the knee buckle or give way

- Hearing a popping sound when the patella dislocates

- Swelling

- A change in the knee’s appearance — the knee may appear misshapen or deformed

- Apprehension or fear when running or changing direction.

Other symptoms can include

-

Activity‐Related Joint Pain

Pain that worsens with weight-bearing activities such as walking or climbing stairs, often subsiding with rest [rx]. -

Morning Stiffness

Transient stiffness upon waking, typically lasting less than 30 minutes, reflecting synovial and capsular inflammation [rx]. -

Reduced Range of Motion (ROM)

Difficulty fully bending (flexion) or straightening (extension) the knee due to cartilage loss and osteophyte impingement [rx]. -

Crepitus

Audible or palpable “crackling” or “grating” sensation with joint movement as roughened cartilage surfaces articulate [rx]. -

Joint Swelling (Effusion)

Increased intra-articular fluid from synovial inflammation causes visible and palpable swelling [rx]. -

Bony Enlargement (Osteophytes)

Palpable hard nodules at joint margins representing new bone growth. -

Joint Instability (“Giving Way”)

Episodes of buckling or giving way due to muscle weakness and structural damage [rx]. -

Pain at Rest

In advanced stages, pain may persist even without activity, interfering with sleep. -

Functional Limitation

Difficulty with activities of daily living (e.g., rising from chair, walking long distances). -

Gait Alteration

Limping or favoring the affected knee to lessen discomfort and instability. -

Joint Line Tenderness

Pain elicited on palpation along the medial or lateral joint line. -

Quadriceps Atrophy

Wasting of the thigh muscles from disuse and pain‐mediated inhibition. -

Muscle Weakness

Loss of strength around the knee reduces shock absorption and contributes to symptoms. -

Painful Crepitus on Palpation

Fine crackling felt under the examiner’s hands during joint movement. -

Limited Weight‐Bearing Tolerance

Early onset fatigue or pain when standing for prolonged periods. -

Locking or Catching

Sensation of the knee catching or locking due to loose bodies or osteophyte impingement. -

Joint Deformity

Visible varus (“bowlegged”) or valgus (“knock‐kneed”) alignment. -

Pain on Palpation of Osteophytes

Localized tenderness over bony spurs. -

Functional Instability

Reduced confidence in using the knee, leading to activity avoidance. -

Crepitus, Clicking, or Popping Sensations

Transient noises beyond crepitus that may indicate meniscal involvement or loose cartilage fragments [rx].

Diagnosis of Knee Osteoarthritis

Patients typically present to their healthcare provider with the chief complaint of knee pain. It is essential to obtain a detailed history of their symptoms. Pay careful attention to history as knee pain can be referred from the lumbar spine or the hip joint. It is equally important to obtain a detailed medical and surgical history to identify any risk factors associated with secondary knee OA.

History

The history of the present illness should include the following

-

Onset of symptoms

-

The specific location of pain

-

Duration of pain and symptoms

-

Characteristics of the pain

-

Alleviating and aggravating factors

-

Any radiation of pain

-

The specific timing of symptoms

-

Severity of symptoms

-

The patient’s functional activity

Physical Examination Tests

Physical examination of the knee should begin with a visual inspection. With the patient standing, look for periarticular erythema and swelling, quadriceps muscle atrophy, and varus or valgus deformities. Observe gait for signs of pain or abnormal motion of the knee joint that can be indicative of ligamentous instability. Inspect the surrounding skin for the presence and location of any scars from previous surgical procedures, overlying evidence of trauma, or any soft tissue lesions.

Range of motion (ROM) testing is a very important aspect of the knee exam. Active and passive ROM with regard to flexion and extension should be assessed and documented.

Palpation along the bony and soft tissue structures is an essential part of any knee exam. The palpatory exam can be broken down into the medial, midline, and lateral structures of the knee.

-

Inspection of Joint Contours

Visual assessment identifies bony enlargements, malalignment (varus/valgus), and muscle atrophy around the knee. -

Palpation for Bony Tenderness

Feeling along the joint line and tibial plateaus reveals areas of pain correlating with cartilage loss. -

Assessment of Range of Motion (ROM)

Goniometric measurement quantifies degrees of flexion and extension, helping track disease progression. -

Evaluation of Crepitus

Applying gentle compression and moving the knee identifies palpable or audible grinding indicative of cartilage roughening. -

Effusion Test (“Ballottement” of the Patella)

Pressing on the suprapatellar pouch with one hand while tapping the patella with the other detects excess fluid in the joint. -

Varus and Valgus Stress Tests

Applying a lateral or medial force with the knee slightly flexed assesses ligament integrity and joint space narrowing on the stressed side. -

Gait and Postural Analysis

Observing walking patterns reveals compensatory mechanisms such as limping, reduced knee flexion during stance, or trunk lean.

Manual Tests

- McMurray Test

Rotating and extending the flexed knee under varus or valgus stress detects meniscal tears, which can mimic or coexist with OA. -

Apley Grind Test

With the patient prone and knee flexed to 90°, axial compression and rotation of the tibia reproduces joint line pain from meniscal or cartilage lesions. -

Lachman Test

Evaluates anterior cruciate ligament integrity and rules out instability that may exacerbate OA. -

Pivot-Shift Test

Assesses anterolateral rotary instability of the knee, helping differentiate ligamentous causes of pain. -

Patellar Grind (Clarke’s) Test

Pressing the patella against the femur while the patient contracts the quadriceps elicits pain in patellofemoral OA.

Laboratory and Pathological Tests

- Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR)

Elevated ESR suggests active inflammation; normal levels support a degenerative rather than inflammatory arthritis. -

C-Reactive Protein (CRP)

CRP levels correlate with synovitis severity; mild elevation may occur in advanced OA. -

Rheumatoid Factor (RF) and Anti-CCP Antibodies

Negative results help exclude rheumatoid arthritis as a cause of knee symptoms. -

Complete Blood Count (CBC)

Evaluates for anemia of chronic disease or leukocytosis that might suggest infection. -

Synovial Fluid Analysis

Aspiration and laboratory examination of joint fluid assess cell count, crystals, and microbiology to exclude septic arthritis or crystal arthropathy. -

Uric Acid Level

Elevated serum urate supports a diagnosis of gout, which can coexist with OA.

Electrodiagnostic Tests

- Surface Electromyography (sEMG)

Measures quadriceps and hamstring muscle activation patterns to assess protective muscle inhibition in OA. -

Needle Electromyography (EMG)

Detects denervation or myopathic changes that may contribute to joint dysfunction. -

Nerve Conduction Studies (NCS)

Evaluate for peripheral neuropathy, which can alter joint sensation and exaggerate pain. -

Quantitative Sensory Testing (QST)

Assesses thresholds for pressure, temperature, and vibration to differentiate nociceptive from neuropathic pain components.

Imaging Tests

- Standard Radiography (X-Ray)

Weight-bearing anteroposterior, lateral, and skyline views reveal joint space narrowing, osteophytes, subchondral sclerosis, and cysts. -

Fluoroscopy-Guided Arthrography

Contrast injection outlines cartilage defects and helps evaluate meniscal integrity when MRI is contraindicated. -

Ultrasound

Dynamic assessment of synovial thickening, effusion, and osteophytes; useful for guiding injections. -

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

High-resolution visualization of cartilage thickness, bone marrow lesions, meniscal pathology, and synovitis without ionizing radiation. -

Computed Tomography (CT) Scan

Detailed bone imaging delineates subchondral cysts and osteophyte morphology; beneficial for surgical planning. -

Bone Scintigraphy (Bone Scan)

Highlights areas of increased osteoblastic activity in early OA or stress injuries not apparent on X-ray. -

Positron Emission Tomography (PET)

Limited to research settings, PET can identify metabolic changes in bone and synovium indicative of active joint remodeling. -

Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry (DEXA)

Although primarily for osteoporosis screening, DEXA can assess bone density around the knee and help differentiate OA from osteopenia.

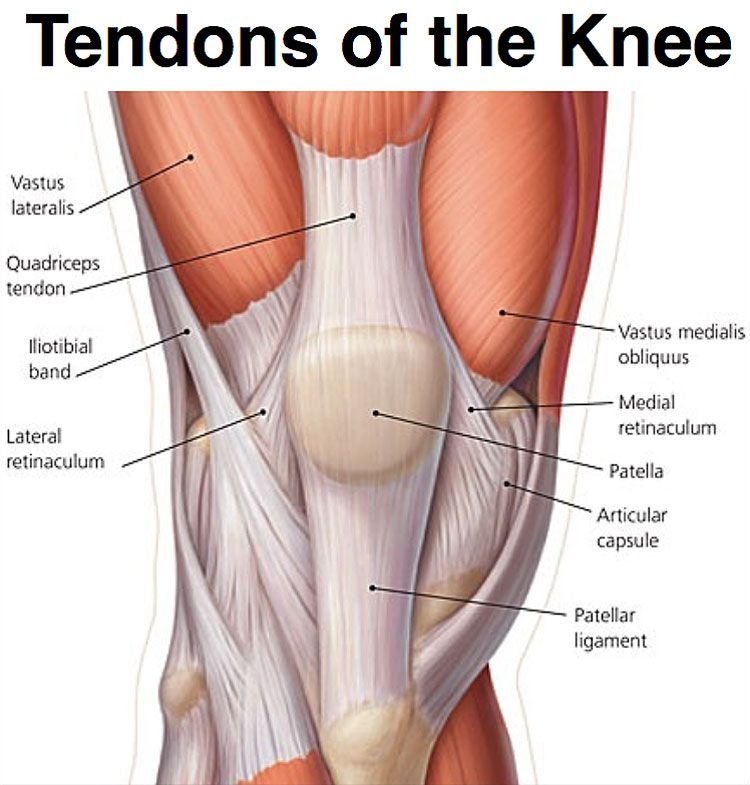

Areas of focus for the medial aspect of the knee

-

Vastus medialis obliquus

-

Superomedial pole patella

-

The medial facet of the patella

-

Origin of the medial collateral ligament (MCL)

-

Midsubstance of the MCL

-

Broad insertion of the MCL

-

Medial joint line

-

Medial meniscus

-

Pes anserine tendons and bursa

Areas of focus for the midline of the knee

-

Quadricep tendon

-

Suprapatellar pouch

-

Superior pole patella

-

Patellar mobility

-

Prepatellar bursa

-

Patellar tendon

-

Tibial tubercle

Areas of focus for the lateral aspect of the knee

-

Iliotibial band

-

Lateral facet patella

-

Lateral collateral ligament (LCL)

-

Lateral joint line

-

Lateral meniscus

-

Gerdy’s tubercle

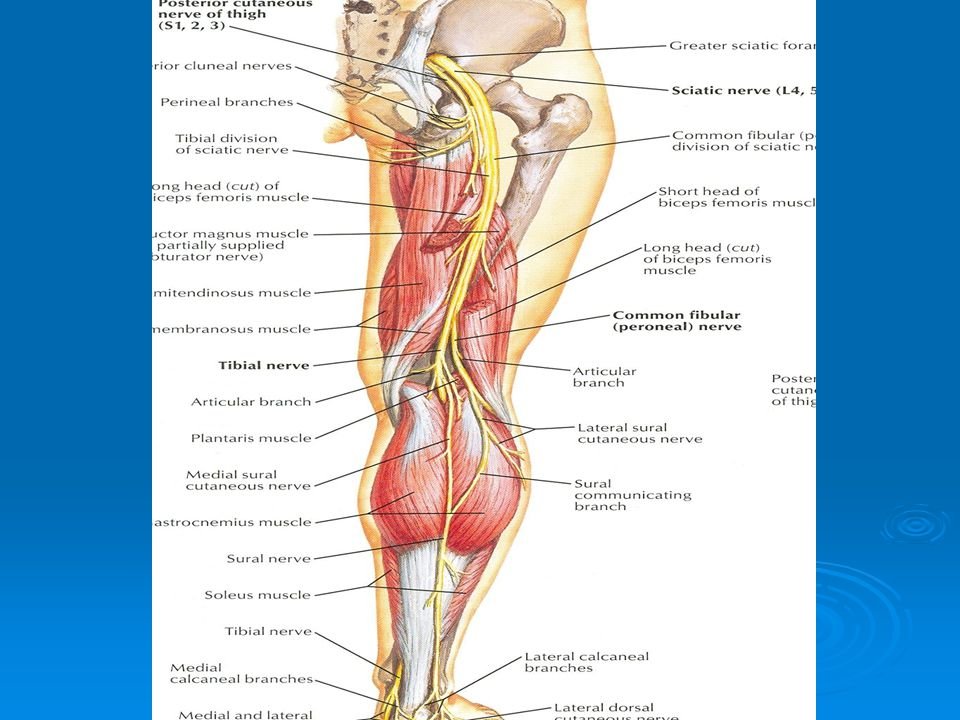

A thorough neurovascular exam should be performed and documented. It is important to assess the strength of the quadriceps and hamstring muscles as these often times will become atrophied in the presence of knee pain. A sensory exam of the femoral, peroneal, and tibial nerve should be assessed as there may be concomitant neurogenic symptoms associated. Palpation of a popliteal, dorsalis pedis and the posterior tibial pulse is important as any abnormalities may raise the concern for vascular problems.

Other knee tests may be performed, depending on the clinical suspicion based on history

Special knee tests

-

Patella apprehension – patellar instability

-

J-sign – patellar maltracking

-

Patella compression/grind – chondromalacia or patellofemoral arthritis

-

Medial McMurray – a medial meniscus tear

-

Lateral McMurray – lateral meniscus tear

-

Thessaly test – a meniscus tear

-

Lachman – anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury

-

Anterior drawer – ACL injury

-

Pivot shift – ACL injury

-

Posterior drawer – posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) injury

-

Posterior sag – PCL injury

-

Quadriceps active test – PCL injury

-

Valgus stress test – MCL injury

-

Varus stress test – LCL injury

Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis

Non-Pharmacological Treatments

Treatment for knee osteoarthritis can be broken down into non-surgical and surgical management. Initial treatment begins with non-surgical modalities and moves to surgical treatment once the non-surgical methods are no longer effective. A wide range of non-surgical modalities is available for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. These interventions do not alter the underlying disease process, but they may substantially diminish pain and disability.[rx][rx][rx]

The 2019 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and EULAR guidelines emphasize education, exercise, weight management, and self-management as core interventions for knee OA. Below are 30 evidence-based, non-drug approaches organized into four categories: physiotherapy & electrotherapy, exercise therapies, mind-body practices, and educational self-management [rx][rx].

A. Physiotherapy and Electrotherapy Therapies

-

Manual Therapy

Hands-on techniques (mobilizations and manipulations) applied by a physiotherapist to improve joint mobility, reduce pain, and promote normal movement patterns. By gently stretching the joint capsule and surrounding soft tissues, manual therapy relieves stiffness and enhances range of motion, facilitating easier daily activities [rx][rx]. -

Therapeutic Ultrasound

High-frequency sound waves penetrate deep tissues to generate gentle heat, promoting blood flow and accelerating tissue healing. This thermal effect can reduce pain and muscle spasms around the knee joint, improving comfort during exercise [rx][rx]. -

Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS)

Low-voltage electrical currents delivered via skin electrodes stimulate sensory nerves, interrupting pain signals to the brain (gate control theory) and triggering endorphin release. While historically used for knee OA, recent ACR guidelines now conditionally recommend against TENS due to mixed efficacy results [rx][rx]. -

Interferential Current Therapy

Two medium-frequency currents intersect beneath the skin, producing a low-frequency therapeutic current that reduces pain and swelling. By enhancing local circulation and modulating nerve conduction, it supports pain relief and muscle relaxation [rx]. -

Shortwave Diathermy

Continuous electromagnetic waves heat deeper tissues, decreasing joint stiffness and improving elasticity of periarticular structures. This deep heating also promotes circulation and may speed recovery after exercise[rx]. -

Pulsed Electromagnetic Field Therapy (PEMF)

Time-varying magnetic fields induce microcurrents in joint tissues, stimulating cartilage repair and reducing inflammation. PEMF has shown promise in animal models and small human studies for alleviating OA pain [rx]. -

Shockwave Therapy

Acoustic waves delivered to the joint area induce microtrauma that triggers a healing cascade, promoting angiogenesis and reducing chronic pain. Emerging evidence suggests benefit for knee OA, though more large-scale trials are needed [rx]. -

Cryotherapy (Cold Therapy)

Application of ice or cold packs to the knee reduces blood flow, swelling, and pain after activity. Cold therapy helps control flare-ups and can be self-administered at home [rx]. -

Thermotherapy (Heat Therapy)

Warm packs or paraffin baths increase blood flow, relax muscles, and reduce stiffness before exercise or daily tasks. Heat can be applied via moist heat packs for 15–20 minutes [rx]. -

Kinesiotaping

Elastic tape applied to the skin provides proprioceptive feedback, improves lymphatic drainage, and supports joint alignment. Taping can reduce pain during movement and may facilitate muscle activation [rx]. -

Whole-Body Vibration

Standing on a vibrating platform transmits mechanical stimuli through the legs, enhancing muscle strength, proprioception, and bone density. Some small studies report reduced knee pain and improved function [rx]. -

Low-Level Laser Therapy

Non-thermal lasers target cellular mitochondria, promoting ATP production and modulating inflammatory pathways. This photobiomodulation can reduce pain and accelerate tissue repair [rx]. -

Electrical Muscle Stimulation (NMES)

Surface electrodes deliver pulses to elicit muscle contractions, strengthening atrophied quadriceps and hamstrings without joint strain. Stronger muscles help stabilize and offload the knee joint[rx]. -

Magnet Therapy

Static magnets applied around the knee are thought to alter ion channels and blood flow, though high-quality evidence is limited. Some patients report symptomatic relief [rx]. -

Electroacupuncture

Combines traditional acupuncture with TENS‐like stimulation via needles, aiming to modulate pain pathways and local inflammation. Conditional support exists for reducing knee OA pain [rx].

B. Exercise Therapies

-

Brisk Walking

Low-impact aerobic exercise that strengthens muscles, improves circulation, and supports joint health. Gradual increase from 10 to 30 minutes most days enhances stamina and reduces pain [rx]. -

Stationary Cycling

Controlled knee motion without weight-bearing load promotes cartilage nutrition and quadriceps strengthening. Begin with low resistance for 10–15 minutes, progressing as tolerated [rx]. -

Resistance Band Training

Elastic bands provide graded muscle resistance, targeting quadriceps, hamstrings, and hip abductors. Stronger muscle support reduces knee joint stress during daily activities [rx]. -

Quadriceps Strengthening (Straight-Leg Raises)

Lying or seated exercises that isolate the quadriceps without bending the knee. Strong quadriceps help absorb shock and stabilize the knee joint [rx]. -

Hamstring Stretching

Gentle stretches of the back of the thigh improve flexibility and reduce posterior knee stress. Hold for 20–30 seconds without bouncing [rx]. -

Heel Raises

Standing calf raises strengthen gastrocnemius and soleus muscles, improving ankle stability and gait, indirectly reducing knee load [rx]. -

Sit-to-Stand Exercises

Repeated rising from a seated position builds functional lower-limb strength and mimics daily activities, enhancing autonomy [rx]. -

Mini-Squats

Partial squats (no more than 45° knee flexion) engage quadriceps and glutes while minimizing joint compression. Start with 5–10 repetitions and increase gradually [rx].

C. Mind-Body Practices

-

Tai Chi

Slow, flowing movements combine balance training, flexibility, and mindfulness. Clinical trials show reduced pain and improved function in knee OA [rx]. -

Yoga

Gentle postures and breathing exercises enhance joint mobility, muscle strength, and stress reduction. Select low-impact poses to protect the knee [rx]. -

Mindfulness Meditation

Mental training to cultivate nonjudgmental awareness of pain sensations, reducing the emotional distress associated with chronic pain [rx]. -

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

Structured psychological intervention teaching coping skills to manage pain, improve adherence to exercise, and reduce catastrophizing [rx].

D. Educational Self-Management

-

Arthritis Self-Management Program (ASMP)

Six weekly group workshops teaching pain management techniques (e.g., goal setting, problem solving, action planning) to enhance self-efficacy and reduce disability [rx]. -

Pain Diary Keeping

Tracking pain triggers, levels, and relief strategies to identify patterns and optimize treatment plans in partnership with clinicians [rx]. -

Peer Support Groups

Group meetings provide education, emotional support, and shared coping strategies, improving motivation and adherence to self-care [rx].

The first-line treatment for all patients with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis includes patient education and physical therapy. A combination of supervised exercises and a home exercise program have been shown to have the best results. These benefits are lost after 6 months if the exercises are stopped.

The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) recommends this treatment.

- Weight loss – is valuable in all stages of knee osteoarthritis. It is indicated in patients with symptomatic arthritis with a body mass index greater than 25. The best recommendation to achieve weight loss is with diet control and low-impact aerobic exercise. There is moderate evidence for weight loss based on the AAOS guidelines.

- Knee bracing – in the setting of osteoarthritis includes unloader-type braces which shift the load away from the involved knee compartment. This may be useful in the setting where either the lateral or medial compartment of the knee is involved such as in a valgus or varus deformity.

- Immobilization – Your doctor may recommend that your child wear a brace for 3 to 4 weeks. This stabilizes the knee while it heals.

- Weightbearing – Because putting weight on the knee may cause pain and slow the healing process, your doctor may recommend using crutches for the first week or two after the injury.

- Physical therapy – Once the knee has started to heal, your child’s doctor will recommend physical therapy to help your child regain normal motion. Specific exercises will strengthen the thigh muscles holding the knee joint in place. Your child’s commitment to the exercise program is important for a successful recovery. Typically, children return to activity 3 to 6 weeks after the injury.

- Emergent closed reduction followed by vascular assessment/consult – indications to considered an orthopedic emergency, vascular consult indicated if pulses are absent or diminished following reduction if arterial injury confirmed by arterial duplex ultrasound or CT angiography

- Immobilization as definitive management – successful closed reduction without vascular compromise, most cases require some form of surgical stabilization following reduction, outcomes of worse outcomes are seen with nonoperative management/prolonged immobilization will lead to loss of ROM with persistent instability.

Rest Your Leg

Once you’re discharged from the hospital in a legislating, your top priority is to rest your and not further inflame the injury. Of course, the arm sling not only provides support, but it also restricts movement, which is why you should keep it on even during sleep. Avoiding the temptation to move your will help the bone mend quicker and the pain fades away sooner.

- Depending on what you do for a living and if the injury is to your dominant side, you may need to take a couple of weeks off work to recuperate.

- Healing takes between four to six weeks in younger people and up to 12 weeks in the elderly, but it depends on the severity of the radial head fractures.

- Athletes in good health are typically able to resume their sporting activities within two months of breaking they’re ulnar styloid depending on the severity of the break and the specific sport.

- Sleeping on your back (with the sling on) is necessary to keep the pressure off your shoulder and prevent stressing the hip injury.

Eat Nutritiously During Your Recovery

- All bones and tissues in the body need certain nutrients in order to heal properly and in a timely manner. Eating a nutritious and balanced diet that includes lots of minerals and vitamins are proven to help heal broken bones of all types. Therefore focus on eating lots of fresh produce (fruits and veggies), whole grains, lean meats, and fish to give your body the building blocks needed to properly repair your. In addition, drink plenty of purified water, milk, and other dairy-based beverages to augment what you eat.

- Broken bones need ample minerals (calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, boron) and protein to become strong and healthy again.

- Excellent sources of minerals/protein include dairy products, tofu, beans, broccoli, nuts and seeds, sardines, and salmon.

- Important vitamins that are needed for bone healing include vitamin C (needed to make collagen), vitamin D (crucial for mineral absorption), and vitamin K (binds calcium to bones and triggers collagen formation).

- Conversely, don’t consume food or drink that is known to impair bone/tissue healing, such as alcoholic beverages, sodas, most fast food items and foods made with lots of refined sugars and preservative.

Follow-Up Care

- You will need to see your doctor regularly until your fracture heals. During these visits, he or they will take x-rays to make sure the bone is healing in a good position. After the bone has healed, you will be able to gradually return to your normal activities.

Medication

- Antibiotic – Cefuroxime or Azithromycin, or Flucloxacillin or any others cephalosporin/quinolone antibiotic must be used to prevent infection or clotted blood remove to prevent furthers swelling and edema.

- NSAIDs – Prescription-strength drugs that reduce both pain and inflammation. Pain medicines and anti-inflammatory drugs help to relieve pain and stiffness, allowing for increased mobility and exercise. There are many common over-the-counter medicines called non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). They include and Ketorolac, Aceclofenac, Naproxen, Etoricoxib.

- Corticosteroids – Also known as oral steroids, these medications reduce inflammation.

- Muscle Relaxants – These medications provide relief from associated muscle spasms.

- Neuropathic Agents – Drugs(pregabalin & gabapentin) that address neuropathic—or nerve-related—pain. This includes burning, numbness, and tingling.

- Opioids – Also known as narcotics, these medications are intense pain relievers that should only be used under a doctor’s careful supervision.

- Topical Medications – These prescription-strength creams, gels, ointments, patches, and sprays help relieve pain and inflammation through the skin.

- Calcium & vitamin D3 – to improve bone health and healing fracture. As a general rule, men and women age 50 and older should consume 1,200 milligrams of calcium a day, and 600 international units of vitamin D a day.

- Dietary supplement-to remove general weakness & improved health.

- Antidepressants – A drug that blocks pain messages from your brain and boosts the effects of endorphins (your body’s natural painkillers).

- Glucosamine & Diacerein, Chondroitin sulfate – can be used to tightening the loose tension, cartilage, ligament, and cartilage, ligament regenerate cartilage or inhabit the further degeneration of cartilage, ligament. They are structural components of articular cartilage, and the thought is that a supplement will aid in the health of articular cartilage. No strong evidence exists that these supplements are beneficial in knee OA; in fact, there is strong evidence against the use according to the AAOS guidelines. There are no major downsides to taking the supplement. If the patient understands the evidence behind these supplements and is willing to try the supplement, it is a relatively safe option. Any benefit gained from supplementation is likely due to a placebo effect.

- Intra-articular corticosteroid injections – may be useful for symptomatic knee osteoarthritis, especially where there is a considerable inflammatory component. The delivery of the corticosteroid directly into the knee may reduce local inflammation associated with osteoarthritis and minimize the systemic effects of the steroid.

- Intra-articular hyaluronic acid injections (HA) – injections are another injectable option for knee osteoarthritis. HA is a glycosaminoglycan that is found throughout the human body and is an important component of synovial fluid and articular cartilage. HA breaks down during the process of osteoarthritis and contributes to the loss of articular cartilage as well as stiffness and pain. Local delivery of HA into the joint acts as a lubricant and may help increase the natural production of HA in the joint.

- Glucocorticoid injections – have a variable response, and there is ongoing controversy regarding repeated injections.

- Duloxetine – has modest efficacy in OA opioids that can be used in those patients without an adequate response to above and who may not be candidates for surgery or refuse it altogether.

Glucosamine With or Without Chondroitin or Chondroitin Alone

Seven studies that assessed the effects of glucosamine, chondroitin or the combination met inclusion criteria. No studies addressed short-term outcomes of glucosamine combined with chondroitin, and no studies addressed the short- or medium-term effects of glucosamine alone.

-

Glucosamine, chondroitin – and the combination of glucosamine plus chondroitin have shown somewhat inconsistent beneficial effects in large, multi-site placebo-controlled and head-to-head trials.

-

Glucosamine + chondroitin – Three large, multi-site RCTs and one smaller RCT found low strength of evidence for a medium-term effect on pain and function but moderate strength of evidence for no long-term benefit on pain and function.

-

Two of the three trials showed a medium-term benefit of glucosamine plus chondroitin on both pain and function (low strength of evidence).

-

A random-effects pooled estimate for three studies showed no effect of long-term treatment on pain compared with control (pooled effect size −0.73, 95% CI −4.03; 2.57) (moderate strength of evidence).

-

A random-effects pooled estimate for all three studies showed no effect of long-term treatment on function compared with control (pooled effect size −0.45, 95% CI −2.75; 1.84) (moderate strength of evidence).

-

-

Glucosamine alone – No RCTs met inclusion criteria for short- or medium-term outcomes. Three RCTs that assessed the effects of long-term glucosamine showed a moderate strength of evidence for no beneficial effects on pain and low strength of evidence for no benefit on function.

-

A random-effects pooled estimate of three studies showed no effect of long-term glucosamine treatment compared with control on pain (n=1007; pooled effect size −0.05, 95% CI −0.22; 0.12; I2 0%) (moderate strength of evidence)

-

Effects of long-term glucosamine on function showed no consistent benefit (low strength of evidence).

-

-

Chondroitin alone: Three RCTs that assessed the effects of chondroitin alone on pain and function showed inconsistent effects across time and outcomes.

-

Two large RCTs showed the significant medium-term benefit of chondroitin alone for pain (low strength of evidence). Evidence was insufficient to assess medium-term effects on function.

-

Three large RCTs showed no long-term benefit of chondroitin alone on pain (moderate strength of evidence) or function (low strength of evidence).

-

-

No studies were identified that compared glucosamine sulfate with glucosamine hydrochloride.

-

No studies analyzed the time course of effects of glucosamine and/or chondroitin, but studies that examined effects at multiple time points showed that the maximum effects are achieved at 3 to 6 months.

Dietary Molecular Supplements

-

Glucosamine Sulfate (1,500 mg/day)

Provides building blocks for glycosaminoglycans in cartilage; may slow cartilage degradation and reduce pain [rx]. -

Chondroitin Sulfate (800–1,200 mg/day)

Attracts water into cartilage matrix, improving viscoelasticity and joint lubrication [rx]. -

Type II Collagen (40 mg/day)

Oral undenatured collagen may induce immune tolerance and support cartilage integrity [rx]. -

Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) (1,500–3,000 mg/day)

Sulfur donor that supports connective tissue synthesis and reduces oxidative stress [rx]. -

Omega-3 Fatty Acids (1,000–2,000 mg EPA/DHA/day)

Produce anti-inflammatory eicosanoids and resolvins, reducing joint inflammation [rx]. Omega-3 Fatty Acids (EPA/DHA) – 1–3 g daily; competes with arachidonic acid, lowers pro-inflammatory prostaglandins. -

Collagen Hydrolysate – 10 g daily; supplies amino acids (glycine, proline) supporting cartilage matrix repair.

-

Vitamin D – 1 000–2 000 IU daily; regulates calcium homeostasis, modulates immune response, low levels linked to OA progression.Modulates bone remodeling and muscle function; deficiency linked to increased OA progression [rx].

-

Vitamin K₂ – 45–90 μg daily; activates matrix Gla protein, inhibits vascular calcification in subchondral bone.

-

Ginger Extract (500–1,000 mg/day)

Inhibits cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase pathways, offering mild analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects[rx]. -

Avocado Soybean Unsaponifiables (ASU) (300 mg/day)

Stimulates collagen synthesis and inhibits interleukin-1, supporting cartilage health [rx]. -

Curcumin (500–1,000 mg/day)

Anti-inflammatory polyphenol that inhibits NF-κB signaling and reduces cytokine release [rx]. -

Boswellia Serrata Extract (100–300 mg frankincense acids/day)

Blocks 5-lipoxygenase, decreasing leukotriene-mediated inflammation [rx].

Advanced (Bisphosphonates, Regenerative, Viscosupplementations, Stem Cell) Drugs

-

Alendronate (70 mg once weekly)

Bisphosphonate that inhibits osteoclast-mediated bone resorption; may reduce subchondral bone sclerosis in OA [rx]. -

Risedronate (35 mg once weekly)

Similar to alendronate; may stabilize subchondral bone and delay progression [rx]. -

Zoledronic Acid (5 mg IV once yearly)

Potent bisphosphonate that reduces bone turnover and may decrease OA pain [rx]. -

Hyaluronic Acid (Viscosupplementation) – 20 mg intra-articular weekly for 3–5 weeks; restores synovial fluid viscosity, cushioning joint impact.

-

Sodium Hyaluronate – varies by product; provides viscoelasticity and may have anti-inflammatory effects on synovium.

-

Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) – 3 injections of autologous plasma enriched with growth factors; promotes cartilage repair and modulates inflammation.

-

Autologous Conditioned Serum (ACS) – 6–8 injections; high IL-1 receptor antagonist content reduces cytokine-driven cartilage damage.

-

Autologous Mesenchymal Stem Cells – 10–50 million cells intra-articularly; differentiate into chondrocytes and secrete trophic factors for regeneration.

-

Allogeneic Stem Cell Products – off-the-shelf MSC injections; similar regenerative aims with immunomodulatory properties.

-

Sprifermin (rhFGF-18) (100–300 µg intra-articular every 6 months)

Recombinant fibroblast growth factor 18 stimulates chondrocyte proliferation and matrix production; 5-year FORWARD trial showed dose-dependent cartilage thickness gains [rx][rx]. -

Anakinra (100 mg intra-articular weekly × 3 weeks)

IL-1 receptor antagonist that blocks cartilage-degrading cytokines; small studies report modest pain improvement [rx]. -

Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) (3 mL intra-articular monthly × 3)

Autologous platelet concentrate releases growth factors (PDGF, TGF-β) to promote tissue repair and reduce inflammation [rx]. -

Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) (1–2 × 10^7 cells intra-articular)

Ex vivo expanded MSCs differentiate into chondrocytes and secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines; early trials demonstrate safety and symptomatic benefit [rx]. -

Umbilical Cord-Derived MSCs (1–5 × 10^6 cells injected)

Allogeneic MSCs with immunomodulatory properties showing structural and pain improvements in small trials [rx]. -

Kartogenin (Phase 1: oral, 100 mg/day)

Small molecule that induces MSC differentiation into chondrocytes via CBFβ–RUNX1 pathway; early human studies ongoing [rx]. -

BMP-7 (Bone Morphogenetic Protein 7) (100 µg intra-articular × 3)

Growth factor supporting osteogenic and chondrogenic gene transcription; Phase 2 trials suggest cartilage preservation [rx].

Surgical Procedures

-

Arthroscopic Lavage and Debridement

Washing out loose debris and trimming damaged cartilage under anesthesia. Provides short-term symptom relief but no long-term structural benefit . -

Microfracture

Drilling small holes in subchondral bone to stimulate marrow stem cells and fibrocartilage formation. Best for small cartilage defects in younger patients . -

Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation (ACI)

Two-stage procedure harvesting and expanding patient’s cartilage cells, then implanting them into defects under a periosteal flap. Produces hyaline-like cartilage with good functional results . -

Osteochondral Autograft Transfer (Mosaicplasty)

Transplanting small plugs of healthy cartilage and bone from non-weight-bearing areas to defects. Provides immediate hyaline cartilage but limited donor tissue . -

High Tibial Osteotomy (HTO)

Cutting and realigning the tibia to shift weight away from the damaged medial compartment, delaying the need for joint replacement. Ideal for younger patients with unicompartmental OA [rx][rx]. -

Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty (Partial Knee Replacement)

Replacing only the diseased compartment with a metal-plastic implant. Faster recovery and more natural knee kinematics than total replacement [rx]. -

Total Knee Arthroplasty (TKA)

Resurfacing both femoral and tibial sides with metal and plastic components. Offers dramatic pain relief and functional improvement in advanced OA [rx]. -

Patellofemoral Arthroplasty

Replacing only the kneecap and trochlear groove for isolated patellofemoral OA. Preserves tibiofemoral joint and native ligaments [rx]. -

Knee Joint Distraction

External fixation temporarily separates joint surfaces to reduce mechanical stress and promote cartilage repair. Early studies show pain relief and tissue regeneration . -

Cartilage Restoration with Hydrogel Scaffolds

Injectable or implantable hydrogels loaded with cells or growth factors support new cartilage formation in focal defects .

Rehabilitation of Knee Osteoarthritis

Strength or Resistance Training

Ten studies that assessed strength or resistance training met inclusion criteria.

-

It is unclear whether strength and resistance training have a beneficial effect on patients with OA of the knee. Pooled analyses support a nonstatistically significant benefit, and individual study findings suggest a possible benefit on pain and function and significant benefit on total WOMAC scores.

-

Strength and resistance training had no statistically significant beneficial effect on short-term pain or function based on pooled analyses of 5 RCTs but a significant short-term beneficial effect on the composite WOMAC total score based on 3 RCTs (low strength of evidence).

-

Strength and resistance training showed a nonsignificant medium-term beneficial effect on function in a pooled analysis of 3 RCTs (low strength of evidence).

-

Evidence was insufficient to assess the long-term effects of strength and resistance training.

-

No studies assessed the effects of any factors such as sex, obesity, or disease severity on outcomes of strength and resistance training.

Cell-based therapies

- Based on our finding of a significant effect of PRP in a small number of small, high RoB studies, and the number of studies that did not meet inclusion criteria because they compared PRP only to HA, we believe a large, saline-controlled trial is needed.

- Although corticosteroids could provide an additional comparator for noninferiority, the immediate adverse effects of intraarticular injection of corticosteroids would be impossible to mask. Residual benefits that remain after the intervention is discontinued (and the effect of follow up treatment) also need to be assessed.

Agility Training

Eight RCTs that assessed the effects of agility training met inclusion criteria.

-

It is unclear whether agility training alone has any benefit for patients with knee OA. Identified studies showed inconsistent effects across time points and outcomes.

-

Agility training showed significant short-term beneficial effects on pain but not on function in 3 RCTs (low strength of evidence).

-

Agility training showed no consistent beneficial effects on medium-term pain or function.

-

Agility training showed no long-term beneficial effect on pain (3 RCTs) or function (2 RCTs) (low strength of evidence).

Aerobic Exercise

Five RCTs that assessed the effects of aerobic exercise met inclusion criteria.

-

Based on five trials, aerobic exercise alone shows no long-term benefit on function; the evidence was insufficient to draw conclusions regarding its effects on short- or medium-term outcomes or on long-term pain for patients with knee OA.

- Evidence was insufficient to draw conclusions about the short-term effects of aerobic exercise on pain, function, and total WOMAC scores (one RCT).

- Evidence was insufficient to draw conclusions about the medium-term effects of aerobic exercise on pain, function, and total WOMAC scores (two RCTs).

- Evidence was insufficient to draw conclusions on the effects of long-term aerobic exercise on pain (2 RCTs)

- The aerobic exercise showed no significant long-term effects on function, based on three RCTs (low evidence).

General Exercise Therapy

Six interventions that combined exercise interventions and did not fit predefined categories were identified.[rx–rx]

-

General exercise programs appear to have beneficial medium-term effects on pain and function and long-term effects on pain for patients with knee OA, based on a relatively small number of heterogeneous RCTs.

- Evidence was insufficient to assess the effects of general exercise therapy programs on short-term pain or function.

- General exercise therapy programs had a beneficial effect on medium-term pain and function, based on two RCTs (low strength of evidence).

- General exercise therapy programs showed beneficial long-term effects on pain, based on 4 RCTs (low strength of evidence), but the evidence was insufficient to assess long-term effects on function or quality of life.

Physical Therapy

- Although there will be some pain, it is important to maintain arm motion to prevent stiffness. Often, patients will begin doing exercises for elbow motion immediately after the injury. It is common to lose some leg strength. Once the bone begins to heal, your pain will decrease and your doctor may start gentle hip, knee exercises. These exercises will help prevent stiffness and weakness. More strenuous exercises will be started gradually once the fracture is completely healed.

Tai Chi

Three RCTs that met inclusion criteria assessed the effects of tai chi compared with resistance training or no activity. rx, rx]

-

Tai chi appears to have some short- and medium-term benefits for patients with OA of the knee, based on three small, short-term RCTs and one larger, 18-week RCT (total n=290).

- Tai chi showed significant beneficial short-term effects on pain, compared with those of conventional physical therapy, in one large RCT, but no significant effects in two small, brief RCTs (low strength of evidence).

- Tai chi showed beneficial effects on short-term function compared with physical therapy and education but not compared with strength training, based on three RCTs (low strength of evidence).

- Tai chi showed significant benefit for medium-term pain and function in 2 RCTs (low strength of evidence).

- Evidence was insufficient to assess the long-term effects of tai chi on pain, function, and other outcomes.

Yoga

One RCT that met inclusion criteria assessed the short-term effects of yoga.[rx]

-

It is unclear whether yoga has any benefit for patients with OA of the knee, as we identified only one small RCT (n=36).

Manual Therapy (Including Massage and Acupressure)

Nine RCTs that assessed the effects of manual therapy (including massage, self-massage, and acupressure) met inclusion criteria.[rx, rx, rx–rx]

-

It is unclear whether manual therapies have any benefit for patients with knee OA beyond the effects of exercise alone. Across nine RCTs, benefits were inconsistent across time points and outcomes. Pooled analysis showed no statistically significant effect on short term pain, although a clinically important effect could not be ruled out, due to the wide 95% confidence intervals.

-

Manual therapy showed no statistically significant beneficial short-term effects on pain compared with treatment as usual, based on a pooled analysis of three RCTs and four additional RCTs (low strength of evidence).

-

Manual therapy showed no consistent beneficial effects on short-term function, based on four RCTs (low strength of evidence).

-

Insufficient evidence was found to assess the medium-term effects of manual therapy on pain, function, and other outcomes, based on four RCTs.

-

Manual therapy had a small beneficial effect on long-term pain of borderline significance when combined with exercise, compared with exercise alone, based on two studies that conducted a 12-month follow-up of three-month interventions (low strength of evidence).

-

Evidence was insufficient to assess effects on long-term function.

Balneotherapy and Mud Treatment

- Four RCTs that met inclusion criteria assessed the effects of balneotherapy, mud baths, or topical mud.[rx–rx] No studies of balneotherapy assessed short- or long-term outcomes.

- Balneotherapy had a beneficial effect on medium-term function, and a beneficial, but the inconsistent effect on medium-term pain across two single-blind RCTs (low strength of evidence). No studies assessed the effects of balneotherapy on short- or long-term outcomes.

- Evidence was insufficient for an effect of mud (mud baths or topical mud) on short-term outcomes.

Heat, Infrared, and Therapeutic Ultrasound

One RCT that assessed the effects of heat,one that assessed the effects of infrared, and three that assessed the effects of pulsed and continuous U/S on outcomes of interest met inclusion criteria.[rx–rx] Only short-term effects were reported for heat and infrared, and no medium-term effects were reported for any of the interventions.

-

Insufficient evidence was identified to determine whether heat or infrared have any beneficial effects on any outcomes in patients with knee OA.

-

Insufficient evidence was identified to determine whether continuous or pulsed therapeutic ultrasound (U/S) have beneficial effects on any outcomes.

TENS and NMES

Four RCTs that compared the effects of TENS with those of sham-TENS[rx–rx] and five RCTs that assessed the effects of NMES met inclusion criteria.[rx, rx–rx] No studies were identified that assessed long-term outcomes.

-

TENS showed a small but significant beneficial short-term effect on pain compared with sham controls based on a pooled analysis of four RCTs (moderate strength of evidence), but no benefit for a short-term function or other outcomes (low strength of evidence). The beneficial effect on pain was not sustained over the medium term.

-

Evidence was insufficient to assess the short-term effects of NMES combined with exercise compared with exercise alone (or NMES compared with a sham control) on pain or function, based on three RCTs.

-

Evidence was insufficient to assess the medium- and long-term effect of NMES on pain and function.

Pulsed Electromagnetic Field (PEMF)

Three RCTs that assessed short-term effects of PEMF on pain met inclusion criteria.[rx–rx] No RCTs were identified that assessed medium- or long-term outcomes of PEMF.

Whole-Body Vibration (WBV)

Seven RCTs that met the inclusion criteria assessed the effects of WBV on outcomes of interest.[rx–rx] No studies that assessed long-term effects were identified.

-

It is unclear whether WBV has a beneficial effect on patients with knee OA, as pooled analysis showed inconsistent effects on pain and function.

-

WBV combined with exercise demonstrated no short-term beneficial effects on pain compared with exercise performed on a stable surface or not combined with WBV, based on three RCTs (low strength of evidence).

-

Evidence is insufficient to draw conclusions on the short-term effects of WBV on function or other outcomes.

-

The WBV-based exercise showed no beneficial medium-term effects on pain, based on pooled analysis of four RCTs (low strength of evidence).

-

The WBV-based exercise showed a small but statistically significant medium-term beneficial effect on WOMAC function, based on a pooled analysis of 4 RCTs (n=180; SMD −0.26, 95% CI −0.45, 0.06) (low strength of evidence) that did not meet the MCID of −0.37. However, no beneficial medium-term effect was observed on the 6-minute walk, based on pooled analysis of four RCTs (low strength of evidence).

Orthoses (Knee Braces, Shoe Inserts, Custom Shoes)

Three RCTs on knee braces eight RCTs on shoe inserts, four RCTs on footwear,[rx–rx] and one RCT on cane use met the inclusion criteria. No RCTs on the short-term effects of footwear were identified.

-

It is unclear whether knee braces – or other orthoses have a beneficial effect on patients with knee OA. Only a small number of RCTs on braces were identified, and studies of shoe inserts and specially designed shoes showed inconsistent effects across time points and outcomes.

-

Knee Braces: Evidence was insufficient to determine whether custom knee braces had significant beneficial effects on any outcomes.

-

Shoe Inserts showed no consistent beneficial effects across outcomes or follow-up times.

-

Custom shoe inserts had no consistent beneficial short-term effects on pain (based on four RCTs), function (three RCTs), or WOMAC total scores (pooled analysis of three RCTs) (low strength of evidence).

-

Shoe inserts showed no statistically significant beneficial effects on medium-term WOMAC pain (based on a pooled analysis of three RCTs) or medium-term function (based on four RCTs) (low strength of evidence).

-

Evidence was insufficient to determine the long-term effects of shoe inserts on pain, but they showed no benefit for long-term function (low strength of evidence).

-

-

Custom shoes: Evidence was insufficient to assess medium- or long-term effects on pain or function.

-

Cane Use: Insufficient evidence exists to assess the benefit of cane use on pain, physical function, and quality of life.

Weight Loss

Five RCTs and five single-arm trials (reported in six publications)[rx–rx] that assessed the effects of weight loss on OA met inclusion criteria.

-

Weight loss with or without exercise has a beneficial effect on medium-term pain and function and on long-term pain but inconsistent effects across studies on long-term function and quality of life.

- Evidence was insufficient to assess short-term effects of dieting, with or without exercise on pain and function,.

- Weight loss had a significant beneficial effect on medium-term pain, based on two RCTs and four single-arm trials. One single-arm trial assessed and reported a dose-response effect between weight and outcomes of interest (moderate-level evidence).

- Weight loss had a significant beneficial effect on medium-term function, based on two RCTs and three single-arm trials (low strength of evidence).

- Weight loss had a significant long-term beneficial effect on pain based on three RCTs and one single-arm trial (low level of evidence) but inconsistent effects on function and quality of life, based on two RCTs (low strength of evidence).

Electrotherapy of Knee Osteoarthritis

Electrotherapy and electrophysical agents include pulsed short-wave therapy (pulsed electromagnetic energy, PEME), interferential therapy, laser, Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) and ultrasound. All are commonly used to treat the signs and symptoms of OA such as pain, trigger point tenderness, and swelling. These modalities involve the introduction of energy into affected tissue resulting in physical changes in the tissue as a result of thermal and non-thermal effects.

Ultrasound

- The therapeutic effects of ultrasound have been classified as relating to thermal and non-thermal effects. Thermal effects cause a rise in temperature in the tissue and non-thermal effects (cavitation, acoustic streaming) can alter the permeability of the cell membrane[rx,rx] which is thought to produce therapeutic benefits[rx].

- The potential therapeutic benefits seen in clinical practice may be more likely in the tissue which has a high collagen content, for example, a joint capsule rather than cartilage and bone which have a lower collagen content.

Pulsed shortwave therapy (Pulsed electromagnetic energy, PEME)

- Pulsed short wave therapy has been purported to work by increasing blood flow, facilitating the resolution of inflammation, and increasing deep collagen extensibility[rx]. The application of this type of therapy can also produce thermal and non-thermal effects. The specific effect may be determined by the specific dose.

Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation or TENS (also termed TNS)

- TENS produces selected pulsed currents that are delivered cutaneously via electrode placement on the skin. These currents can activate specific nerve fibers potentially producing analgesic responses. TENS is recognized as a treatment modality with minimal contraindications[rx].

- The term AL-TENS is not commonly used in the UK. It involves switching between high and low-frequency electrical stimulation and many TENS machines now do this. The term is more specific to stimulating acupuncture points.

Interferential therapy

- Interferential therapy can be described as the transcutaneous application of alternating medium-frequency electrical currents and may be considered a form of TENS. Interferential therapy may be useful in pain relief, promoting healing, and producing muscular contraction[rx].

Laser

- The laser is an acronym for Light Amplification by the Stimulated Emission of Radiation. Therapeutic applications of low intensity or low-level laser therapy at doses considered too low to affect any detectable heating of the tissue have been applied to treat musculoskeletal injury[rx].

Surgical Treatment Options[rx]

Open Reduction

- irreducible knee

- posterolateral dislocation

- open fracture-dislocation

- obesity (may be difficult to obtain closed)

- vascular injury

External Fixation

- vascular repair (takes precedence)

- open fracture-dislocation

- compartment syndrome

- obese (if difficult to maintain reduction)

- polytrauma patient

Delayed Ligamentous Reconstruction/Repair

- instability will require some kind of ligamentous repair or fixation

- patients can be placed in a knee immobilizer until treated operatively

- improved outcomes with early treatment (within 3 weeks)

Arthroscopy +/- Open Debridement

- Arthroscopic or open debridement with removal of any loose bodies may be necessary for displaced osteochondral fractures or loose bodies.

MPFL Re-Attachment Or Reconstruction (Proximal Realignment)

- Proximal realignment constitutes the reconstruction of the MPFL. In brief, to repair the ligament, a longitudinal incision is made at the border of the VMO, just anterior to the medial epicondyle. The ligament is usually re-attached to the femur using bone anchors. If the patient has had recurrent dislocations, then reconstruction may be necessary by harvesting gracilis or semitendinosus which are then attached to the patella and femur.

- Isolated repair/reconstruction of the MPFL is not a recommendation in those with bony abnormalities including TT-TG distance greater than 20mm, convex trochlear dysplasia, severe patella alta, advanced cartilage degeneration or severe femoral anteversion.[rx]

Lateral Release (Distal Realignment)

- A lateral release cuts the retinaculum on the lateral aspect of the knee joint. The aim is to improve the alignment of the patella by reducing the lateral pull.

Osteotomy (Distal Realignment)

- Where there is abnormal anatomy contributing to poor patella tracking and a high TT-TG distance, the alignment correction can be through an osteotomy. The most common procedure of this type is known as the Fulkerson-type osteotomy and involves an osteotomy as well as removing the small portion of bone to which the tendon attaches and repositioning it in a more anteromedial position on the tibia.

Trochleoplasty

- Trochleoplasty is indicated in recurrent dislocators with a convex or flat trochlea. The trochlear groove is deepened to create a groove for the patella to glide through; this may take place alongside an MPFL reconstruction. Studies suggest it is not advisable in those with open growth plates or severely degenerative joints. This procedure is uncommon except in refractory cases.

High Tibial Osteotomy (HTO)

-

Osteotomy

-

Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA)

-

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA)

A high tibial osteotomy (HTO) may be indicated for unicompartmental knee osteoarthritis associated with malalignment. Typically an HTO is done for varus deformities where the medial compartment of the knee is worn and arthritic. The ideal patient for an HTO would be a young, active patient in whom arthroplasty would fail due to excessive component wear. An HTO preserves the actual knee joint, including the cruciate ligaments, and allows the patient to return to high-impact activities once healed. It does require additional healing time compared to an arthroplasty, is more prone to complications, depends on bone and fracture healing, is less reliable for pain relief, and ultimately does not replace cartilage that is already lost or repair any remaining cartilage. An osteotomy will delay the need for arthroplasty for up to 10 years.

Indications for HTO

-

Young (less than 50 years old), active patient

-

Healthy patient with good vascular status

-

Non-obese patients

-

Pain and disability interfering with daily life

-

Only one knee compartment is affected

-

A compliant patient who will be able to follow the postoperative protocol

Contraindications for HTO

-

Inflammatory arthritis

-

Obese patients

-

Knee flexion contracture greater than 15 degrees

-

Knee flexion less than 90 degrees

-

If the procedure will need greater than 20 degrees of deformity correction

-

Patellofemoral arthritis

-

Ligamentous instability

A UKA also is indicated in unicompartmental knee osteoarthritis. It is an alternative to an HTO and a TKA. It is indicated for older patients, typically 60 years or older, and relatively thin patients; although, with newer surgical techniques the indications are being pushed.

Indications for UKA

-

Older (60 years or older), lower demand patients

-

Relatively thin patients

Contraindications for UKA

-

Inflammatory arthritis

-

ACL deficiency

-

Fixed varus deformity greater than 10 degrees

-

Fixed valgus deformity greater than 5 degrees

-

Arc of motion less than 90 degrees

-

Flexion contracture greater than 10 degrees

-

Arthritis is more than one compartment

-

Younger, higher activity patients or heavy laborers

-

Patellofemoral arthritis

A TKA is the surgical treatment option for patients failing conservative management and those with osteoarthritis in more than one compartment. It is regarded as a valuable intervention for patients who have severe daily pain along with radiographic evidence of knee osteoarthritis.

Indications for TKA

-

Symptomatic knee OA in more than one compartment

-

Failed non-surgical treatment options

Contraindications for TKA

Absolute

-

Active or latent knee infection

-

Presence of active infection elsewhere in the body

-

Incompetent quadriceps muscle or extensor mechanism

Relative

-

Neuropathic arthropathy

-

Poor soft-tissue coverage

-

Morbid obesity

-

Noncompliance due to major psychiatric disorder or alcohol or drug abuse

-

Insufficient bone stock for reconstruction

-

Poor health or presence of comorbidities that make the patient an unsuitable candidate for major surgery and anesthesia

-

Patient’s poor motivation or unrealistic expectations

-

Severe peripheral vascular disease

Advantages of UKA vs TKA

-

Faster rehabilitation and quicker recovery

-

Less blood loss

-

Less morbidity

-

Less expensive

-

Preservation of normal kinematics

-

Smaller incision

-

Less post-surgical pain and shorter hospital stay

Advantages of UKA vs HTO

-

Faster rehabilitation and quicker recovery

-

Improved cosmesis

-

The higher initial success rate

-

Fewer short-term complications

-

Lasts longer

-

Easier to convert to TKA

Complications of Knee Osteoarthritis

Complications associated with non-surgical treatment are largely associated with NSAID use.

Common Adverse Effects of NSAID Use

-

Stomach pain and heartburn

-

Stomach ulcers

-

A tendency to bleed, especially while taking aspirin

-

Kidney problems

Common Adverse Effects of Intra-Articular Corticosteroid Injection

-

Pain and swelling (cortisone flare)

-

Skin discoloration at the site of injection

-

Elevated blood sugar

-

Infection

-

Allergic reaction

Common Adverse Effects of Intra-Articular HA Injection

-

Injection site pain

-

Muscle pain

-

Trouble walking

-

Fever

-

Chills

-

Headache

Complications Associated with HTO

-

Recurrence of deformity

-

Loss of posterior tibial slope

-

Patella baja

-

Compartment syndrome

-

Peroneal nerve palsy

-

Malunion or nonunion

-

Infection

-

Persistent pain

-

Blood clot

Complications Associated with UKA

-

Stress fracture of the tibia

-

Tibial component collapse

-

Infection

-

Osteolysis

-

Persistent pain

-

Neurovascular injury

-

Blood clot

Complications Associated with TKA

-

Infection

-

Instability

-

Osteolysis

-

Neurovascular injury

-

Fracture

-

Extensor mechanism rupture

-

Patellar maltracking

-

Patellar clunk syndrome

-

Stiffness

-

Peroneal nerve palsy

-

Wound complications

-

Heterotopic ossification

-

Blood clot

References