A Retrolisthesis is a posterior displacement of one vertebral body with respect to the subjacent vertebra to a degree less than a luxation (dislocation). Retrolistheses are most easily diagnosed on lateral x-ray views of the spine. Views where care has been taken to expose for a true lateral view without any rotation offer the best diagnostic quality. Retrolistheses are found most prominently in the cervical spine and lumbar region but can also be seen in the thoracic area.

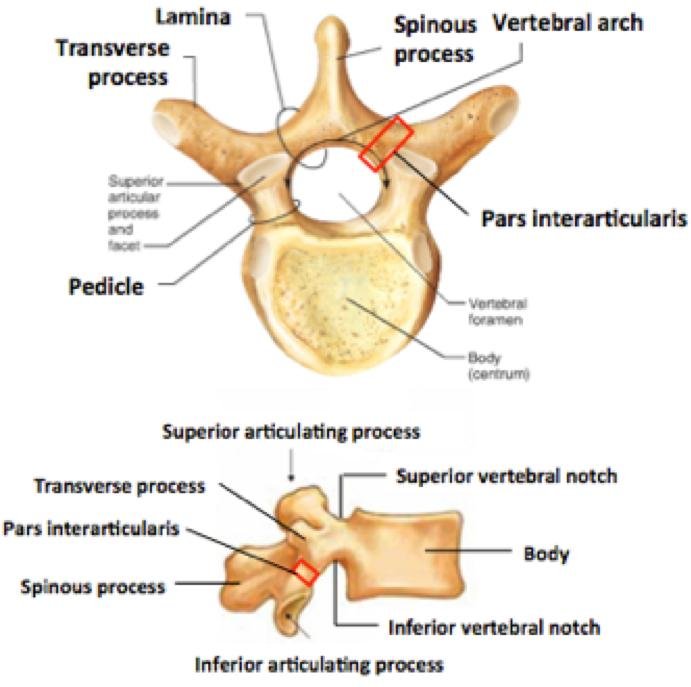

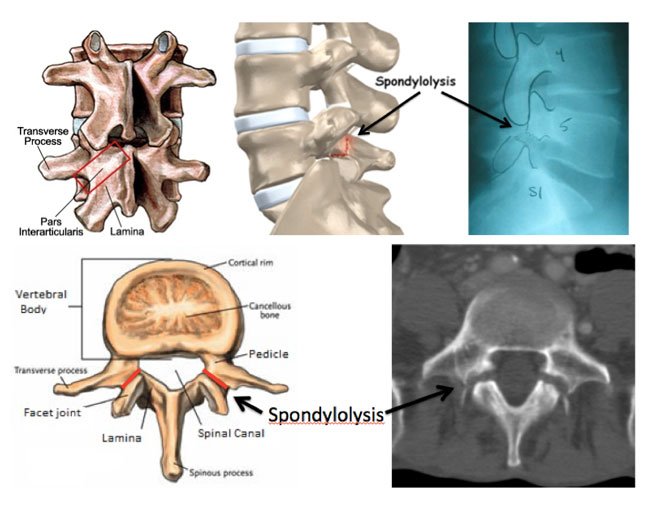

Spondylolysis is a unilateral or bilateral defect in the region of the pars interarticularis, which may or may not be accompanied by vertebral displacement, and is most commonly the result of repetitive trauma to the growing immature skeleton of a genetically susceptible individual. [rx][rx][rx] The pars interarticularis is considered the isthmus or bone bridge between the inferior and superior articular surfaces of a single vertebra. [rx][rx][rx]

Types of Spondylolisthesis and Pars

- Complete Retrolisthesis – The body of one vertebra is posterior to both the vertebral body of the segment of the spine above as well as below.

- Stairstepped Retrolisthesis – The body of one vertebra is posterior to the body of the spinal segment above, but is anterior to the one below.

- Partial Retrolisthesis – The body of one vertebra is posterior to the body of the spinal segment either above or below

Spondylolisthesis, a related condition to spondylolysis, is defined by the forward displacement of the upper vertebra relative to the caudal vertebra.

In 1976 Wiltse et al.[rx] classified spondylolisthesis into five types:

-

Type I or dysplastic – is attributed to congenital dysplasia of the superior articular process of the sacrum.

-

Type II or isthmic – is due to a lesion in the pars interarticularis; these subclassify as:

-

(a) Lytic, when a fatigue pars fracture is present

-

(b) Pars elongation due to multiple healed stress fractures

-

(c) Acute pars fracture

-

-

Type III or degenerative – originates from facet instability without a pars fracture.

-

Type IV or traumatic – the displacement is due to an acute posterior arch fracture other than pars.

-

Type V or pathological – is due to posterior vertebral arch bone disease.[rx]

-

Type VI or iatrogenic – it is a potential sequel to spinal surgery.

For this activity, the focus will be on type II or isthmic spondylolisthesis.

Spondylolisthesis was classified by Meyerding et al. [rx] in five subtypes according to the magnitude of slippage on plain lateral lumbar radiograph measured in accordance to the inferior vertebra.

-

Grade I, less than 25% of displacement,

-

Grade II, between 25 and 50%,

-

Grade III, between 50 and 75%,

-

Grade IV, between 75 and 100% and

-

Grade V or spondyloptosis, when there is no contact between the vertebrae endplates. The commonly used Grade V, representing more than a 100% slip or spondyloptosis, is not part of the original grading system.

The majority of pars lesions or spondylolysis occur at L5 (85 to 95%), with L4 being the second most commonly affected vertebra (5 to 15%). The other lumbar levels are less often affected.[rx][rx][rx][rx][rx] The defect is unilateral in 22% of the cases.

Causes of Retrolisthesis

These sports include gymnastics and dance as the highest prevalence with an increased incidence also seen in football (particularly linemen), rugby, wrestling, martial arts, soccer, basketball, cheerleading, pitching, golf, tennis, volleyball servers, weightlifting, and butterfly and breaststroke swimming.[rx][rx][rx][rx]

Pars defects (spondylolysis) subdivide into five categories according to the Wiltse-Newman Classification[rx]

-

Dysplastic – congenital abnormalities/attenuated pars (approximately 20%)

-

Isthmic – lesions in the pars resulting from a stress fracture or acute fractures (approximately 50%)

-

Type II-A: pars fatigue fracture

-

Type II-B: pars elongation due to a healed fracture

-

Type II-C: pars acute fracture

-

-

Degenerative – degeneration of the intervertebral discs that results in segmental instability and alterations of the articular processes

-

A traumatic – acute fracture that results in fractures to various regions of the neural arch

-

Pathological – bone disease such as tumors and infections that result in lesions to the pars

There are many causes of spondylolisthesis including congenital, degenerative, traumatic, pathologic, iatrogenic, and isthmic. Isthmic spondylolisthesis, which will be the topic of this discussion, refers to a defect in the pars interarticularis that then results in anterior subluxation over time, most commonly at L5-S1 followed by L4-5. The resulting anterior subluxation can produce back pain, central canal stenosis, and lateral recess or foraminal stenosis.

Symptoms of Retrolisthesis

- Numbness or tingling – People who have a herniated disk often have radiating numbness or tingling in the body part served by the affected nerves.

- Weakness – Muscles served by the affected nerves tend to weaken. This can cause you to stumble, or affect your ability to lift or hold items.

- A general stiffening of the back and a tightening of the hamstrings, with a resulting change in both posture and gait.

- A leaning-forward or semi-kyphotic posture may be seen, due to compensatory changes.

- A “waddle” may be seen in more advanced causes, due to compensatory pelvic rotation due to decreased lumbar spine rotation.

- A result of the change in gait is often a noticeable atrophy in the gluteal muscles due to lack of use.

- Generalized lower-back pain may also be seen, with intermittent shooting pain from the buttocks to the posterior thigh, and/or lower leg via the sciatic nerve.

- Pain in the neck, back, low back, arms, or legs

- Inability to bend or rotate the neck or back

- Numbness or tingling in the neck, shoulders, arms, hands, hips, legs, or feet

- Weakness in the arms or legs

- Limping when walking

- Increased pain when coughing, sneezing, reaching, or sitting

- Inability to stand up straight; being “stuck” in a position, such as stooped forward or leaning to the side

- Difficulty getting up from a chair

- Inability to remain in 1 position for a long period of time, such as sitting or standing, due to pain

- Pain that is worse in the morning

- This is a sharp, often shooting pain that extends from the buttock down the back of one leg. It is caused by pressure on the spinal nerve.

- Numbness or a tingling sensation in the leg and/or foot

- Weakness in the leg and/or foot

Diagnosis of Retrolisthesis

Physical Exam

- The major components of the physical exam for spondylolisthesis consists of observation, palpation, and maneuvers. The most common finding is pain with lumbar extension. Neurological examination is often normal in patients with spondylolisthesis, but lumbosacral radiculopathy is commonly seen in patients with degenerate spondylolisthesis.[rx]

Observation

- The patient should be observed walking and standing. Most patients present with a normal gait. An abnormal gait is often the sign of a high-grade case. A patient with high-grade spondylolisthesis may present with a posterior pelvic tilt causing a loss in the normal contour of the buttocks. An antalgic gait, rounded back and decreased hip extension, can result from severe pain. [rx][rx]

Palpation

- Detection of spondylolisthesis by palpation is most often done by palpating for the spinous process.[rx] Each level of the lumbar spine should be palpated. Spinous process palpation by itself is not a definitive method for the detection of spondylolisthesis.[rx]

Maneuvers

- Spinal range of motion testing – Range of motion limitations may be seen.

- Lumbar hyperextension – Extension often elicits pain. This can be assessed by having the patient hyperextend the lumbar spine, provide resistance against back extensions, or undergo repeated lumbar extensions.

- Sport-specific motion – Patients can be asked to repeat aggravating movements that they experience during their activity. During the movement, ask the patient to point to any places with focal pain.

- Straight leg raise – Maneuver used to assess for hamstring tightness. The straight leg raise has been found to be positive in only 10% of patients with spondylolisthesis.[rx]

- Muscle strength exercises – Lower abdominal, gluteal, and lumbar extensors should be assessed for weakness. Weakness in these muscles can increase lordosis and contribute to sacroiliac instability.[rx] Abdominal flexor strength can be assessed with the abdominal flexor endurance test. The test involves the patient lying supine while holding a 45 degree flexed trunk and 90 degree flexed knees for 30 seconds. Gluteal strength can be assessed with a single leg squat. Lastly, a lumbar extension can be assessed with a single leg bridge.

Imaging

- Scintigraphy – is an excellent screening tool for low back pain in children or adolescents. It has shown high sensitivity for the detection of acute injuries and bone stress reaction in the pars. However, some lesions may not display an increased contrast uptake.

- Computed tomography scan (CT) – may be helpful in some cases due to its higher specificity. The tomographic finding of an acute injury include the margin reabsorption in the pars; pars sclerosis may indicate chronic stress, and marginal sclerosis with widening may indicate a chronic condition.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) – offers advantages in terms of visualizing other types of pathology present in the lumbar spine and may potentially detect pars edema secondary to stress in their clinical course.[rx] The lack of ionizing radiation with MRI may also make it a particularly desirable modality for studying pars lesions, especially in the female adolescent population.[rx]

- Electrodiagnostic testing – (Electromyography and nerve conduction studies) can be an option in patients that demonstrate equivocal symptoms or imaging findings as well as to rule out the presence of a peripheral mononeuropathy. The sensitivity of detecting cervical radiculopathy with electrodiagnostic testing ranges from 50% to 71%.[rx]

- The straight leg raise test – With the patient lying supine, the examiner slowly elevates the patient’s led at an increasing angle, while keeping the leg straight at the knee joint. The test is positive if it reproduces the patient’s typical pain and paresthesia.[rx]

- The contralateral (crossed) straight leg raise test – As in the straight leg raise test, the patient is lying supine, and the examiner elevates the asymptomatic leg. The test is positive if the maneuver reproduces the patient’s typical pain and paresthesia. The test has a specificity greater than 90%.

- Myelography – An X-ray of the spinal canal following the injection of contrast material into the surrounding cerebrospinal fluid spaces will reveal the displacement of the contrast material. It can show the presence of structures that can cause pressure on the spinal cord or nerves, such as herniated discs, tumors, or bone spurs.

Treatment of Retrolisthesis

There is insufficient evidence to support the natural course or treated pars defect as the preferred management. Management generally reflects the following treatment algorithm. [rx][rx][rx]

- Symptomatic spondylolysis (type II)

- Symptomatic low-grade spondylolisthesis

-

Physical therapy program for 6 months and include

-

Hamstring stretching

-

Pelvic tilts

-

Core strengthening

-

TLSO bracing for 6 to 12 weeks

- Acute pars stress reaction

- Spondylolysis (type II) that has failed to improve with physical therapy

- Low-grade spondylolisthesis that has failed to improve with physical therapy

- Brace immobilization is superior to activity restriction alone for acute stress reaction

Non-Pharmacological Treatment

Conservative Treatments – Acute cervical or lumbar radiculopathies secondary to pars interarticularis injury a are typically managed with non-surgical treatments as the majority of patients (75 to 90%) will improve. Modalities that can be used include[rx][rx][rx]:

- Rest the area by avoiding any activity that causes worsening symptoms in the arms or legs.

- Stay active around the house, and go on short walks several times per day. The movement will decrease pain and stiffness and help you feel better.

- Apply ice packs to the affected area for 15 to 20 minutes every 2 hours.

- Sit in firm chairs. Soft couches and easy chairs may make your problems worse.

-

Deep tissue massage may be helpful

-

Acupuncture – In acupuncture, the therapist inserts fine needles into certain points on the body with the aim of relieving pain.

-

Reiki – Reiki is a Japanese treatment that aims to relieve pain by using specific hand placements.

-

Moxibustion – This method is used heat specific parts of the body (called “therapy points”) by using glowing sticks made of mugwort (“Moxa”) or heated needles that are put close to the therapy points.

-

Massages – Various massage techniques are used to relax muscles and ease tension.

-

Heating and cooling – This includes the use of hot packs and plasters, a hot bath, going to the sauna, or using an infrared lamp. Heat can also help relax tense muscles. Cold packs, like cold wraps or gel packs, are also used to help with irritated nerves.

-

Ultrasound therapy – Here the lower back is treated with sound waves. The small vibrations that are produced generate heat to relax body tissue.

-

Cervical Manipulation – There is limited evidence suggesting that cervical manipulation may provide short-term benefits for neck pain and pars interarticularis injury. Complications from manipulation are rare and can include worsening radiculopathy, myelopathy, spinal cord injury, and vertebral artery injury. These complications occur ranging from 5 to 10 per 10 million manipulations.

-

Lumbar Corset or Collar for Immobilization – In patients with acute neck pain, a short course (approximately one week) of collar immobilization may be beneficial during the acute inflammatory period.

- Traction – May be beneficial in reducing the radicular symptoms associated with pars interarticularis injury. Theoretically, traction would widen the neuroforamen and relieve the stress placed on the affected nerve, which, in turn, would result in the improvement of symptoms. This therapy involves placing approximately 8 to 12 lbs of traction at an angle of approximately 24 degrees of neck flexion over a period of 15 to 20 minutes.

Physical Therapy

- Exercising in water – can be a great way to stay physically active when other forms of exercise are painful. Exercises that involve lots of twisting and bending may or may not benefit you. Your physical therapist will design an individualized exercise program to meet your specific needs.

- Weight-training exercises – though very important, need to be done with proper form to avoid stress to the back and neck.

- Reduce pain and other symptoms – Your physical therapist will help you understand how to avoid or modify the activities that caused the injury, so healing can begin. Your physical therapist may use different types of treatments and technologies to control and reduce your pain and symptoms.

- Improve posture –If your physical therapist finds that poor posture has contributed to your herniated disc, the therapist will teach you how to improve your posture so that pressure is reduced in the injured area, and healing can begin and progress as rapidly as possible.

- Improve motion – Your physical therapist will choose specific activities and treatments to help restore normal movement in any stiff joints. These might begin with “passive” motions that the physical therapist performs for you to move your spine, and progress to “active” exercises and stretches that you do yourself. You can perform these motions at home and in your workplace to help hasten healing and pain relief.

- Improve flexibility – Your physical therapist will determine if any of the involved muscles are tight, start helping you to stretch them, and teach you how to stretch them at home.

- Improve strength – If your physical therapist finds any weak or injured muscles, your physical therapist will choose, and teach you, the correct exercises to steadily restore your strength and agility. For neck and back disc herniations, “core strengthening” is commonly used to restore the strength and coordination of muscles around your back, hips, abdomen, and pelvis.

- Improve endurance – Restoring muscular endurance is important after an injury. Your physical therapist will develop a program of activities to help you regain the endurance you had before the injury, and improve it.

- Learn a home program – Your physical therapist will teach you strengthening, stretching, and pain-reduction exercises to perform at home. These exercises will be specific for your needs; if you do them as prescribed by your physical therapist, you can speed your recovery.

Eat Nutritiously During Your Recovery

- All bones and tissues in the body need certain nutrients in order to heal properly and in a timely manner. Eating a nutritious and balanced diet that includes lots of minerals and vitamins are proven to help heal broken bones of all types. Therefore focus on eating lots of fresh produce (fruits and veggies), whole grains, lean meats, and fish to give your body the building blocks needed to properly repair your. In addition, drink plenty of purified water, milk, and other dairy-based beverages to augment what you eat.

- Broken bones need ample minerals (calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, boron) and protein to become strong and healthy again.

- Excellent sources of minerals/protein include dairy products, tofu, beans, broccoli, nuts and seeds, sardines, and salmon.

- Important vitamins that are needed for bone healing include vitamin C (needed to make collagen), vitamin D (crucial for mineral absorption), and vitamin K (binds calcium to bones and triggers collagen formation).

- Conversely, don’t consume food or drink that is known to impair bone/tissue healing, such as alcoholic beverages, sodas, most fast food items, and foods made with lots of refined sugars and preservatives.

Medication

Pharmacotherapy – There is no evidence to demonstrate the efficacy of non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) in the treatment of cervical radiculopathy. However, they are commonly used and can be beneficial for some patients. The use of COX-1 versus COX-2 inhibitors does not alter the analgesic effect, but there may be decreased gastrointestinal toxicity with the use of COX-2 inhibitors. Clinicians can consider steroidal anti-inflammatories (typically in the form of prednisone) in severe acute pain for a short period. A typical regimen is prednisone 60 to 80 mg/day for five days, which can then be slowly tapered off over the following 5 m to 14 days. Another regimen involves a prepackaged tapered dose of Methylprednisolone that tapers from 24 mg to 0 mg over 7 days.

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) – These painkillers belong to the same group of drugs as acetylsalicylic acid (ASA, the drug in medicines like “Aspirin”). NSAIDs that may be an option for the treatment of sciatica include diclofenac, ibuprofen, and naproxen. Anti-inflammatory drugs are drugs that reduce inflammation. This includes substances produced by the body itself like cortisone. It also includes artificial substances like ASA – acetylsalicylic acid (or “aspirin”) or ibuprofen –, which relieve pain and reduce fever as well as reducing inflammation.

-

Acetaminophen (paracetamol) – Acetaminophen (paracetamol) is also a painkiller, but it is not an NSAID. It is well tolerated and can be used as an alternative to NSAIDs – especially for people who do not tolerate NSAID painkillers because of things like stomach problems or asthma. But higher doses of acetaminophen can cause liver and kidney damage. The package insert advises adults not to take more than 4 grams (4000 mg) per day. This is the amount in, for example, 8 tablets containing 500 milligrams each. It is not only important to take the right dose, but also to wait long enough between doses.

-

Opioids – Strong painkillers that may only be used under medical supervision. Opioids are available in many different strengths, and some are available in the form of a patch. Morphine, for example, is a very strong drug, while tramadol is a weaker opioid. These drugs may have a number of different side effects, some of which are serious.

- Skeletal Muscle relaxant – If muscle spasms are prominent, the addition of a muscle relaxant may merit consideration for a short period. For example, cyclobenzaprine is an option at a dose of 5 mg taken orally three times daily. Antidepressants (amitriptyline) and anticonvulsants (gabapentin and pregabalin) have been used to treat neuropathic pain, and they can provide a moderate analgesic effect.

-

Steroids – Anti-inflammatory drugs that can be used to treat various diseases systemically. That means that they are taken as tablets or injected. The drug spreads throughout the entire body to soothe inflammation and relieve pain. Steroids may increase the risk of gastric ulcers, osteoporosis, infections, skin problems, glaucoma, and glucose metabolism disorders.

-

Muscle relaxants – Sedatives which also relax the muscles. Like other psychotropic medications, they can cause fatigue and drowsiness, and affect your ability to drive. Muscle relaxants can also affect liver functions and cause gastro-intestinal complications. Drugs from the benzodiazepine group, such as tetrazepam, can lead to dependency if they are taken for longer than two weeks.

- Nerve Relaxant and Neuropathic Agents – Drugs(pregabalin & gabapentin) or Vitamin B1 B6, B12 and mecobalamin that address neuropathic—or nerve-related pain remover. This includes burning, numbness, and tingling.

-

Anticonvulsants – These medications are typically used to treat epilepsy, but some are approved for treating nerve pain (neuralgia). Their side effects include drowsiness and fatigue. This can affect your ability to drive.

- Antidepressants – These drugs are usually used for treating depression. Some of them are also approved for the treatment of pain. Possible side effects include nausea, dry mouth, low blood pressure, irregular heartbeat, and fatigue.

- Topical Medications – These prescription-strength creams, gels, ointments, patches, and sprays help relieve pain and inflammation through the skin.

- Calcium & vitamin D3 – to improve bone health and healing fracture. As a general rule, men and women age 50 and older should consume 1,200 milligrams of calcium a day, and 600 international units of vitamin D a day.

- Glucosamine & Diacerein, Chondroitin sulfate – can be used to tightening the loose tension, cartilage, ligament, and cartilage, ligament regenerate cartilage or inhabit the further degeneration of cartilage, ligament

- Injections near the spine – Injection therapy uses mostly local anesthetics and/or anti-inflammatory medications like corticosteroids (for example cortisone). These drugs are injected into the area immediately surrounding the affected nerve root. There are different ways of doing this:

-

In lumbar spinal nerve analgesia (LSPA) – the medication is injected directly at the point where the nerve root exits the spinal canal. This has a numbing effect on the nerve root.

-

In lumbar epidural analgesia – the medication is injected into what is known as the epidural space (“epidural injection”). The epidural space surrounds the spinal cord and the spinal fluid in the spinal canal. This is also where the nerve roots are located. During this treatment, the spine is monitored using computer tomography or X-rays to make sure that the injection is placed at exactly the right spot.

-

Interventional Treatments – Spinal steroid injections are a common alternative to surgery. Perineural injections (translaminar and transforaminal epidurals, selective nerve root blocks) are an option with pathological confirmation by MRI. These procedures should take place under radiologic guidance.[rx]

-

Surgical treatment

There are no clear radiological or medical guidelines or indications for surgical interventions in degenerative spondylolisthesis.[rx] A minimum of three months of conservative management should be completed prior to considering surgical intervention.[rx] Three indications for potential surgical treatment are as follows: persistent or recurrent back pain or neurologic pain with a persistent reduction of quality of life despite a reasonable trial of conservative (non-operative) management, new or worsening bladder or bowel symptoms, or a new or worsening neurological deficit.[rx][rx]:

-

Pars defect that has failed nonoperative management

-

Multiple pars defects

-

Low-grade spondylolisthesis (Myerding grade I & II) that fails conservative treatment, is progressive, has neurologic deficits, or likely to progress

-

Posterolateral fusion

-

Bucks fusion of facet joints

- High-grade spondylolisthesis (Myerding grade III, IV, V)

- Direct pars interarticularis repair

Additionally, on the discovery of the condition, vitamin D should be checked, and repleted levels are low.

References