An ear infection is an inflammation of the middle ear, usually caused by bacteria, that occurs when fluid builds up behind the eardrum. Anyone can get an ear infection, but children get them more often than adults. Five out of six children will have at least one ear infection by their third birthday. Ear infections are the most common reason parents bring their children to a doctor. The scientific name for an ear infection is otitis media (OM).

What are the symptoms of an ear infection?

There are three main types of ear infections. Each has a different combination of symptoms.

- Acute otitis media (AOM) is the most common ear infection. Parts of the middle ear are infected and swollen and fluid is trapped behind the eardrum. This causes pain in the ear—commonly called an earache. Your child might also have a fever.

- Otitis media with effusion (OME) sometimes happens after an ear infection has run its course and fluid stays trapped behind the eardrum. A child with OME may have no symptoms, but a doctor will be able to see the fluid behind the eardrum with a special instrument.

- Chronic otitis media with effusion (COME) happens when fluid remains in the middle ear for a long time or returns over and over again, even though there is no infection. COME makes it harder for children to fight new infections and also can affect their hearing.

How can I tell if my child has an ear infection?

Most ear infections happen to children before they’ve learned how to talk. If your child isn’t old enough to say “My ear hurts,” here are a few things to look for:

- Tugging or pulling at the ear(s)

- Fussiness and crying

- Trouble sleeping

- Fever (especially in infants and younger children)

- Fluid draining from the ear

- Clumsiness or problems with balance

- Trouble hearing or responding to quiet sounds

What causes an ear infection?

An ear infection usually is caused by bacteria and often begins after a child has a sore throat, cold, or other upper respiratory infection. If the upper respiratory infection is bacterial, these same bacteria may spread to the middle ear; if the upper respiratory infection is caused by a virus, such as a cold, bacteria may be drawn to the microbe-friendly environment and move into the middle ear as a secondary infection. Because of the infection, fluid builds up behind the eardrum.

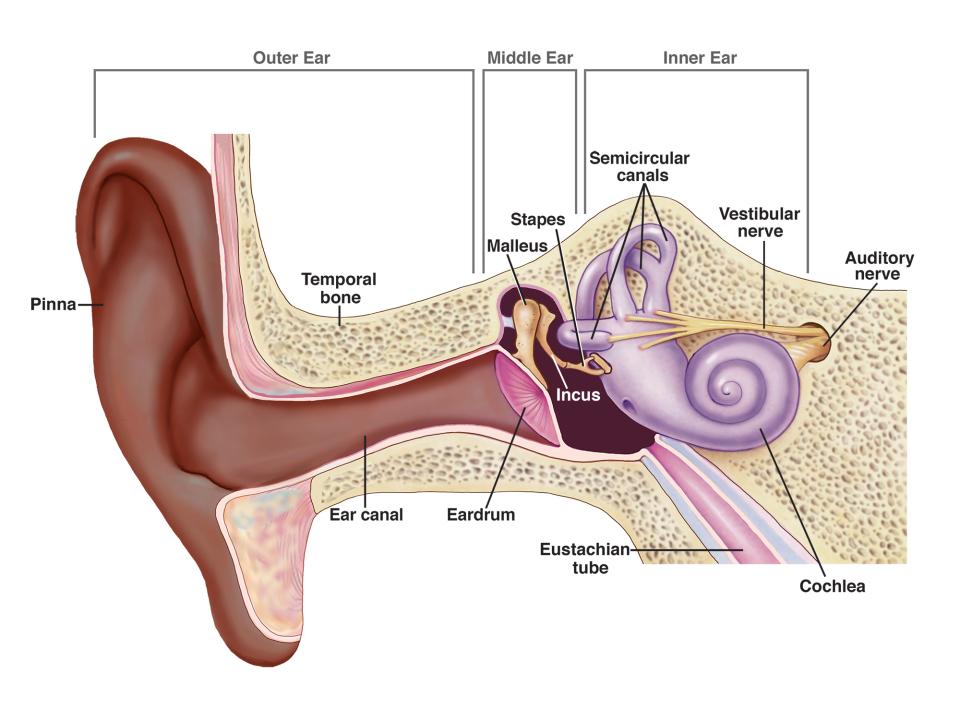

The ear has three major parts: the outer ear, the middle ear, and the inner ear. The outer ear also called the pinna, includes everything we see on the outside—the curved flap of the ear leading down to the earlobe—but it also includes the ear canal, which begins at the opening of the ear and extends to the eardrum. The eardrum is a membrane that separates the outer ear from the middle ear.

The middle ear—which is where ear infections occur—is located between the eardrum and the inner ear. Within the middle ear are three tiny bones called the malleus, incus, and stapes that transmit sound vibrations from the eardrum to the inner ear. The bones of the middle ear are surrounded by air.

The inner ear contains the labyrinth, which helps us keep our balance. The cochlea, a part of the labyrinth, is a snail-shaped organ that converts sound vibrations from the middle ear into electrical signals. The auditory nerve carries these signals from the cochlea to the brain.

Other nearby parts of the ear also can be involved in ear infections. The eustachian tube is a small passageway that connects the upper part of the throat to the middle ear. Its job is to supply fresh air to the middle ear, drain fluid, and keep air pressure at a steady level between the nose and the ear.

These causes and risk factors include:

-

Decreased immunity due to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), diabetes, and other immuno-deficiencies

-

Genetic predisposition

-

Mucins which include abnormalities of this gene expression, especially upregulation of MUC5B

-

Anatomic abnormalities of the palate and tensor veli palatini

-

Ciliary dysfunction

-

Cochlear implants

-

Vitamin A deficiency

-

Bacterial pathogens, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenza, and Moraxella (Branhamella) catarrhalis are responsible for more than 95%

-

Viral pathogens such as respiratory syncytial virus, influenza virus, parainfluenza virus, rhinovirus, and adenovirus

-

Allergies

-

Lack of breastfeeding

-

Passive smoke exposure

-

Daycare attendance

-

Lower socioeconomic status

-

Family history of recurrent AOM in parents or siblings

Adenoids are small pads of tissue located behind the back of the nose, above the throat, and near the eustachian tubes. Adenoids are mostly made up of immune system cells. They fight off infection by trapping bacteria that enter through the mouth.

Why are children more likely than adults to get ear infections?

There are several reasons why children are more likely than adults to get ear infections.

Eustachian tubes are smaller and more level in children than they are in adults. This makes it difficult for fluid to drain out of the ear, even under normal conditions. If the eustachian tubes are swollen or blocked with mucus due to a cold or other respiratory illness, fluid may not be able to drain.

A child’s immune system isn’t as effective as an adult’s because it’s still developing. This makes it harder for children to fight infections.

As part of the immune system, the adenoids respond to bacteria passing through the nose and mouth. Sometimes bacteria get trapped in the adenoids, causing a chronic infection that can then pass on to the eustachian tubes and the middle ear.

How does a doctor diagnose a middle ear infection?

The first thing a doctor will do is ask you about your child’s health. Has your child had a head cold or sore throat recently? Is he having trouble sleeping? Is she pulling at her ears? If an ear infection seems likely, the simplest way for a doctor to tell is to use a lighted instrument, called an otoscope, to look at the eardrum. A red, bulging eardrum indicates an infection.

A doctor also may use a pneumatic otoscope, which blows a puff of air into the ear canal, to check for fluid behind the eardrum. A normal eardrum will move back and forth more easily than an eardrum with fluid behind it.

Tympanometry, which uses sound tones and air pressure, is a diagnostic test a doctor might use if the diagnosis still isn’t clear. A tympanometer is a small, soft plug that contains a tiny microphone and speaker as well as a device that varies air pressure in the ear. It measures how flexible the eardrum is at different pressures.

Laboratory Studies

Laboratory evaluation is rarely necessary. A full sepsis workup in infants younger than 12 weeks with fever and no obvious source other than associated acute otitis media may be necessary. Laboratory studies may be needed to confirm or exclude possible related systemic or congenital diseases.

Imaging Studies

Imaging studies are not indicated unless intra-temporal or intracranial complications are a concern.[rx][rx]

-

When an otitis media complication is suspected, computed tomography of the temporal bones may identify mastoiditis, epidural abscess, sigmoid sinus thrombophlebitis, meningitis, brain abscess, subdural abscess, ossicular disease, and cholesteatoma.

-

Magnetic resonance imaging may identify fluid collections, especially in the middle ear collections.

Tympanocentesis

Tympanocentesis may be used to determine the presence of middle ear fluid, followed by culture to identify pathogens.

Tympanocentesis can improve diagnostic accuracy and guide treatment decisions but is reserved for extreme or refractory cases.[rx][rx]

Other Tests

Tympanometry and acoustic reflectometry may also be used to evaluate for middle ear effusion.[rx]

How is an acute middle ear infection treated?

Many doctors will prescribe an antibiotic, such as amoxicillin, to be taken over seven to 10 days. Your doctor also may recommend over-the-counter pain relievers such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen, or eardrops, to help with fever and pain. (Because aspirin is considered a major preventable risk factor for Reye’s syndrome, a child who has a fever or other flu-like symptoms should not be given aspirin unless instructed to by your doctor.)

Once the diagnosis of acute otitis media is established, the goal of treatment is to control pain and to treat the infectious process with antibiotics. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or acetaminophen can be used to achieve pain control. There are controversies about prescribing antibiotics in early otitis media, and the guidelines may vary by country, as discussed above. Watchful waiting is practiced in European countries with no reported increased incidence of complications. However, watchful waiting has not gained wide acceptance in the United States. If there is clinical evidence of suppurative AOM, however, oral antibiotics are indicated to treat this bacterial infection, and high-dose amoxicillin or a second-generation cephalosporin are first-line agents. If there is a TM perforation, treatment should proceed with ototopical antibiotics safe for middle-ear use such as ofloxacin, rather than systemic antibiotics, as this delivers much higher concentrations of antibiotics without any systemic side effects.[rx]

When a bacterial etiology is suspected, the antibiotic of choice is high-dose amoxicillin for ten days in both children and adult patients who are not allergic to penicillin. Amoxicillin has good efficacy in the treatment of otitis media due to its high concentration in the middle ear. In cases of penicillin allergy, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends azithromycin as a single dose of 10 mg/kg or clarithromycin (15 mg/kg per day in 2 divided doses). Other options for penicillin-allergic patients are cefdinir (14 mg/kg per day in 1 or 2 doses), cefpodoxime (10 mg/kg per day, once daily), or cefuroxime (30 mg/kg per day in 2 divided doses).

For those patients whose symptoms do not improve after treatment with high dose amoxicillin, high-dose amoxicillin-clavulanate (90 mg/kg per day of amoxicillin component, with 6.4 mg/kg per day of clavulanate in 2 divided doses) should be given. In children who are vomiting or if there are situations in which oral antibiotics cannot be administered, ceftriaxone (50 mg/kg per day) for three consecutive days, either intravenously or intramuscularly, is an alternative option. Systemic steroids and antihistamines have not been shown to have any significant benefits.[rx][rx]

Patients who have experienced four or more episodes of AOM in the past twelve months should be considered candidates for myringotomy with tube (grommet) placement, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines. Recurrent infections requiring antibiotics are clinical evidence of Eustachian tube dysfunction, and placement of the tympanostomy tube allows ventilation of the middle ear space and maintenance of normal hearing. Furthermore, should the patient acquire otitis media while a functioning tube is in place, they can be treated with ototopical antibiotic drops rather than systemic antibiotics.[rx]

If your doctor isn’t able to make a definite diagnosis of OM and your child doesn’t have severe ear pain or a fever, your doctor might ask you to wait a day or two to see if the earache goes away. The American Academy of Pediatrics issued guidelines in 2013 that encourage doctors to observe and closely follow these children with ear infections that can’t be definitively diagnosed, especially those between the ages of 6 months and 2 years. If there’s no improvement within 48 to 72 hours from when symptoms began, the guidelines recommend doctors start antibiotic therapy. Sometimes ear pain isn’t caused by infection, and some ear infections may get better without antibiotics. Using antibiotics cautiously and with good reason helps prevent the development of bacteria that become resistant to antibiotics.

If your doctor prescribes an antibiotic, it’s important to make sure your child takes it exactly as prescribed and for the full amount of time. Even though your child may seem better in a few days, the infection still hasn’t completely cleared from the ear. Stopping the medicine too soon could allow the infection to come back. It’s also important to return for your child’s follow-up visit so that the doctor can check if the infection is gone.

How long will it take my child to get better?

Your child should start feeling better within a few days after visiting the doctor. If it’s been several days and your child still seems sick, call your doctor. Your child might need a different antibiotic. Once the infection clears, fluid may remain in the middle ear but usually disappears within three to six weeks.

What happens if my child keeps getting ear infections?

To keep a middle ear infection from coming back, it helps to limit some of the factors that might put your child at risk, such as not being around people who smoke and not going to bed with a bottle. Despite these precautions, some children may continue to have middle ear infections, sometimes as many as five or six a year. Your doctor may want to wait for several months to see if things get better on their own but, if the infections keep coming back and antibiotics aren’t helping, many doctors will recommend a surgical procedure that places a small ventilation tube in the eardrum to improve airflow and prevent fluid backup in the middle ear. The most commonly used tubes stay in place for six to nine months and require follow-up visits until they fall out.

If the placement of the tubes still doesn’t prevent infections, a doctor may consider removing the adenoids to prevent infection from spreading to the eustachian tubes.

Can ear infections be prevented?

Currently, the best way to prevent ear infections is to reduce the risk factors associated with them. Here are some things you might want to do to lower your child’s risk for ear infections.

- Vaccinate your child against the flu. Make sure your child gets influenza, or flu, vaccine every year.

- It is recommended that you vaccinate your child with the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13). The PCV13 protects against more types of infection-causing bacteria than the previous vaccine, the PCV7. If your child already has begun PCV7 vaccination, consult your physician about how to transition to PCV13. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that children under age 2 be vaccinated, starting at 2 months of age. Studies have shown that vaccinated children get far fewer ear infections than children who aren’t vaccinated. The vaccine is strongly recommended for children in daycare.

- Wash hands frequently. Washing hands prevents the spread of germs and can help keep your child from catching a cold or the flu.

- Avoid exposing your baby to cigarette smoke. Studies have shown that babies who are around smokers have more ear infections.

- Never put your baby down for a nap, or the night, with a bottle.

- Don’t allow sick children to spend time together. As much as possible, limit your child’s exposure to other children when your child or your child’s playmates are sick.

What research is being done on middle ear infections?

Researchers sponsored by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) are exploring many areas to improve the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of middle ear infections. For example, finding better ways to predict which children are at higher risk of developing an ear infection could lead to successful prevention tactics.

Another area that needs exploration is why some children have more ear infections than others. For example, Native American and Hispanic children have more infections than children in other ethnic groups. What kinds of preventive measures could be taken to lower the risks?

Doctors also are beginning to learn more about what happens in the ears of children who have recurring ear infections. They have identified colonies of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, called biofilms, that are present in the middle ears of most children with chronic ear infections. Understanding how to attack and kill these biofilms would be one way to successfully treat chronic ear infections and avoid surgery.

Understanding the impact that ear infections have on a child’s speech and language development is another important area of study. Creating more accurate methods to diagnose middle ear infections would help doctors prescribe more targeted treatments. Researchers also are evaluating drugs currently being used to treat ear infections, and developing new, more effective, and easier ways to administer medicines.

References