Diseases of the Cranial Nerves 12 mean the specific abnormality that is happening in cranial nerves are peripheral nerves except for the optic nerve which is a central nervous system tract. Disorders of particular note include the following: Olfactory (I) nerve—anosmia is most commonly encountered as a sequel to head injury.

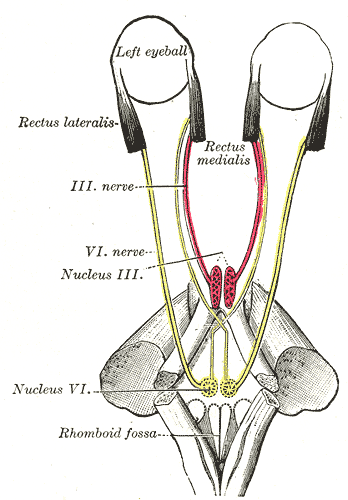

Third, fourth, and sixth cranial nerves—complete lesions lead to the following deficits

- (1) third nerve—a dilated and unreactive pupil, complete ptosis, and loss of upward, downward, and medial movement of the eye;

- (2) fourth nerve—extorsion of the eye when the patient looks outwards, with diplopia when the gaze is directed downwards and medially;

- (3) sixth nerve—convergent strabismus, with the inability to abduct the affected eye and diplopia maximal on lateral gaze to the affected side. The third, fourth, and sixth nerves may be affected singly or in combination: in older patients, the commonest cause is a vascular disease of the nerves themselves or their nuclei in the brainstem.

- Other causes of lesions include (1) false localizing signs—third or sixth nerve palsies related to the displacement of the brainstem produced by supratentorial space-occupying lesions; (2) intracavernous aneurysm of the internal carotid artery—third, fourth, and sixth nerve lesions. Lesions of these nerves can be mimicked by myasthenia gravis

Diseases of the Cranial Nerves – Test and Examination

Facial nerve palsy is paresis of the muscles supplied by the facial nerve (VII) on 1 side of the face due to a lesion of the facial nerve. The paresis generally only occurs on 1 side, but it may also occur on both sides. Usually, it is temporary. Initially, the patient suffers from non-specific dragging pain in the region of the ear before the paresis develops over several hours or days.

This occurs in 10–35 cases/100,000 inhabitants. During pregnancy, the prevalence increases 3 times, especially in the 1st trimester. This condition has a universal distribution and has no predilection for ethnicity or age.

Possible causes for facial nerve paresis:

- Viral and bacterial infections

- Stroke/ischemic lesions

- Basal skull fracture

- Tumors in the petrous bone or the parotid gland

- Intracranial injury

- Toxic causes

- Idiopathic causes

- Chromosomal damage

Depending on the location of the lesion, one distinguishes between central and peripheral facial nerve palsy.

In both, rehabilitation must be started as soon as possible to avoid complications.

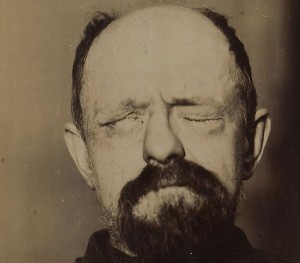

Peripheral facial nerve paresis

Peripheral facial nerve paresis involves lesions of the 2nd motor neuron, the anterior motor horn, the peripheral nerves, or the muscles outside the central nervous system. Peripheral facial nerve palsy is characterized by a weakened myotatic reflex, negative pyramidal tract signs, a slack tone, and atrophy of the affected muscles.

Idiopathic facial nerve palsy (Bell’s palsy) is the most frequent peripheral cranial nerve lesion, and it is accompanied by a single-sided and acute occurrence of peripheral facial nerve palsy. This disease can occur at any age, often between the ages of 10–20 and 30–40 years. Women seem to be affected more frequently than men.

Bell’s palsy heals in approx. 70% of cases without any consequences, but persistent defects after re-innervation may remain.

As a consequence of 1-sided peripheral facial palsy, the following actions are no longer possible:

- Frowning

- Raising eyebrows

- Closing the eyes

- Puffing out the cheeks

- Whistling

- Showing the teeth

These symptoms also suggest the failure of the nerve, and weakness or complete paresis of the mimic muscles may result. Symptoms include:

- Bell’s phenomenon (incomplete closure of the eyelid)

- Upward rotation of the eyeball becomes visible

- Drooping of the labial angle and the lower eyelid

- Elapsed nasolabial fold

- Slackened platysma

Disorders of lacrimation, headache, gustatory disturbances in the anterior 3rd of the tongue, ear pain, and increased hearing sensation are other accompanying symptoms.

Causes of Bell’s palsy are:

- Herpes zoster infections

- Otitis media

- Guillain-Barré syndrome

- HIV infection tumor

- Ischemic stroke

- Autoimmune disease

- Lyme disease

- Among others.

Central facial palsy

Central facial palsy is due to a lesion of the 1st motor neuron in the region of the brain or its descending projections to the spinal cord.

Central facial palsy involves increased myotatic reflexes, weakened multisynaptic reflexes, and positive pyramidal tract signs; a cramp-like increase in the tone of the affected muscles also occurs, without any relevant atrophy. Frequently, central facial palsies are caused by cerebral circulatory impairments or brain tumors.

In contrast to peripheral facial palsy, a patient with central facial palsy can frown and close his eyelid since the peripheral nuclear areas (facial nucleus) lead to the fibers of the facial nerve and are interconnected to finally reach the forehead and the eye, which also receive fibers from the other side.

The musculature is no longer mobile – especially in the area of the mouth – and it is flaccid, as with peripheral facial palsy. Also, the labial angle droops are immobile and are partially open on the affected side.

Note: A distinguishing feature of peripheral and central facial palsy: with central facial palsy, the patient can frown and close his eyelid.

Trigeminal Neuralgia

Trigeminal neuralgia occurs in the innervation area of the trigeminal nerve in the form of a severe, acute, and recurrent attack-like facial pain that is generally single-sided. Three forms are distinguished:

- Classic trigeminal neuralgia: in patients with compression of the trigeminal nerve by a presumed or demonstrated vascular loop

- Secondary trigeminal neuralgia: associated with another disease such as multiple sclerosis and tumors

- Idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia: when the cause is unknown

Other categories include several causes of facial pain such as painful trigeminal neuropathy due to herpes zoster virus, post-traumatic trigeminal neuropathy, painful trigeminal neuropathy attributed to other disorders, and idiopathic painful trigeminal neuropathy.

Classic trigeminal neuralgia

Previously called tic douloureux. The principal cause of this pain is the compression or mechanical irritation of the trigeminal nerve by blood vessel loops at the point where it exits the brainstem. The average age of onset is between 50–79 years.

Symptomatic trigeminal neuralgia

This form of trigeminal neuralgia accompanies demyelination diseases such as multiple sclerosis, which occurs as a consequence of either tumors or Costen’s syndrome (e.g., a facial pain that originates from the facial muscles due to malfunction of the mandibular joint). Inflammatory processes and, in rare cases, medical interventions can result in trigeminal neuralgia.

Symptomatic trigeminal neuralgia may be accompanied by hypoesthesia, i.e. reduced sensitivity towards tactile stimuli, in the form of numbness or tingling, in the region of the 1st trigeminal branch. Furthermore, the corneal reflex is weakened.

Patients with symptomatic trigeminal neuralgia are, on average, younger than patients with the classical form of the disease (tic doulourex). Double-sided facial pain often also occurs in such patients. The goal of therapy is to treat the underlying cause.

Symptoms of trigeminal neuralgia:

- Attacks of shooting and severe pain, which occurs repeatedly, up to 100 times a day

- Mostly, the supply area of the 2nd branch of the trigeminal nerve is affected

- It can be triggered by touch, coldness, speaking, swallowing, chewing, combing hair, touching or washing the face, spicy food, vibration at walking, etc.

- Due to the pain, patients are sad, powerless, anorexic, they sleep badly, and they feel weak

The patients try to avoid the trigger by reducing their mimic movement, not speaking, and not eating. Often, only fluid foods are taken in with a straw. In the cold seasons, most patients protect themselves from the cold and the wind with a scarf.

Eye muscle paresis

Oculomotor nerve palsy

The oculomotor nerve (the eye movement nerve) innervates several eye muscles and – along with the trochlear nerve (IV) and the abducens nerve (VI) – is responsible for the movement of the eyeball.

Roughly/3rd of all eye muscle pareses are caused by oculomotor nerve palsy, which is overall slightly rarer than abducens nerve palsy. In 60–70% of cases, oculomotor nerve palsy occurs as an isolated loss.

Lesions of this nerve can result in various types of paresis: complete (inner and outer) oculomotor nerve palsy.

Complete loss of the function of the nerve leads to the following clinical picture:

- Ptosis (drooping of the upper eyelid)

- The eyeball deviates to the outside and downwards

- Widened pupil (mydriasis) and pupils unresponsive to light (totally unresponsive pupil)

- Diplopia (double vision)

In cases of complete oculomotor nerve palsy, the consensual reaction of the opposite eye remains, i.e. a reflex-triggered concordant reaction occurs on the opposite side of the body. The opening of the eyelid may be possible through contraction of the frontal muscle since double vision only occurs following the elevation of the eyelid.

Causes of oculomotor nerve palsy are:

- Tumor

- Stroke

- Infections of the central nervous system (meningitis or encephalitis)

- Aneurysm

- A local lesion in the base of the eye.

Ophthalmoplegia interna

Ophthalmoplegia interna involves completely unresponsive pupils accompanied by the free movement of the eyeball; the pupil does not react to either direct or indirect light nor convergence. As a result, the patient does not have a clear vision in the affected eye when looking at close objects. There is also paresis of accommodation.

Ophthalmoplegia externa

In cases of ophthalmoplegia externa, however, the motility of the eyeball is impaired, yet autonomous innervation of the pupil and the ciliary muscle is intact. If pupil function has been preserved, complete paresis of all the muscles innervated by the oculomotor nerve is quite rare.

Anisocoria

Another disease or deficit of the oculomotor nerve would be pupils of unequal width, which is referred to as anisocoria. Anisocoria is present in Claude-Bernard- Horner syndrome, which is characterized by constriction of the pupil (miosis), a drooping eyelid (ptosis), anhidrosis (decreased sweating), and posterior displacement of the eyeball (enophthalmos).

Anisocoria can also occur alongside intracranial pressure involving compression of the oculomotor nerve.

Trochlear Nerve Palsy

Trochlear nerve palsies are rarer than oculomotor or abducens nerve palsies. The most frequent cause of monosymptomatic trochlear nerve palsy is a traumatic brain injury.

Trochlear nerve palsy is characterized by isolated paresis of the superior oblique muscle. The function of this muscle is to depress the eyeball. In cases of paresis, the symptom increases during adduction and is virtually absent during abduction, i.e. the eye of the patient faces towards the nose and upwards, and the patient experiences double vision (diplopia), just as in cases of oculomotor nerve palsy.

Causes of trochlear nerve palsy are tumor, demyelination, meningitis, and other.

A distinction is made between double and single-sided trochlear nerve palsy.

Double-sided trochlear nerve palsy

In cases of double-sided trochlear nerve palsy, the Bielschowsky phenomenon is often positive on both sides. In this case, the diseased eye stands higher, is rotated outwards to the temple, and has a squint deviation to the nose, which creates oblique double vision. To compensate, the patient tries to rotate and lower the chin and to tilt the head to the healthy side.

Compensatory head-turning and tilting are usually not present, in contrast to 1-sided trochlear nerve palsy.

One-sided trochlear nerve palsy

One-sided trochlear nerve palsy is accompanied by a compensatory head posture with turning and tilting towards the healthy shoulder and lowering of the chin. The affected eye is in an abduction position and is rotated outwards. An annoying pathological rolling image is avoided since the slackened internal rotator is not utilized this way.

Abducens nerve palsy

The abducens nerve palsy is characterized by an isolated paresis of the rectus lateralis muscle (an externally turning muscle), which often occurs without identifiable intracranial lesions. In a high percentage of cases, the cause of these palsies remains idiopathic. However, trauma, a diabetic metabolic state, and increased intracranial pressure due to tumor or meningitis are some causes of abducens nerve palsy.

In cases of abducens nerve palsy, convergent paralytic strabismus occurs even in the primary position, i.e. the affected eye deviates towards the inside and the paralyzed eye is impaired or inhibited if it tries to turn to look to the side or to look up.

Furthermore, a slight adduction position can occur when looking up or down. Undisturbed binocular movement is, however, observed when looking to the healthy side.

Horizontally parallel double images (i.e. double vision) are usually perceived even in the primary position. The deviation of the images of objects on the retina increases on the paralyzed side, but when the affected eye is covered, the image corresponding to the respective side disappears.

However, the annoying phenomenon of double vision causes a compensatory head posture, which leads to the head being turned towards the side of the paralyzed muscle – a position that does not require the rectus lateralis muscle.

Lesions of the visual pathway

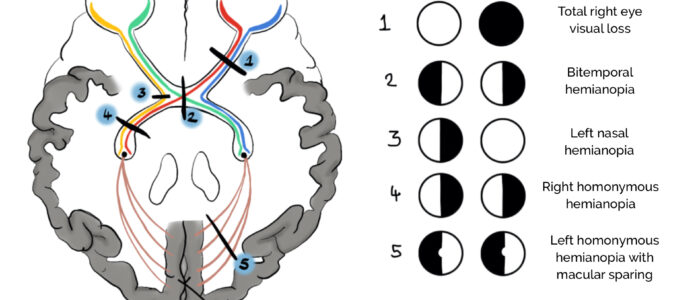

Each optic tract consists of ‘2 half, former’ optical nerves. They conduct the lateral part of the visual information coming from the same side and also the medial sensations of the opposite side.

The visual pathway crosses the whole brain. Very differing deficits in the visual field may arise depending on the location of the lesion. Therefore, when there is a lesion in the visual pathway, the visual field is examined, and pupil reaction and the appearance of the papilla are examined.

The following deficits in the visual field can occur as a result of nerve lesions:

- If the optic nerve is severely damaged on 1 side, the patient is blind on the affected eye, and their sight is not impaired on the other side.

- When there is a lesion of the medial part of the optic chiasm, it is mainly the fibers that cross to the other side that are damaged. The patient can suffer from a bitemporal (heteronymous) hemianopsia, i.e the patient does not get any visual information relating to what happens in his lateral field of vision. This is referred to as hemianopsia, or ‘blinker vision.’ The lateral section, which does not cross and leads to the optic tract, remains intact, meaning sight in this part of the visual field is not impaired.

- Visual loss can also affect the optic tract. For example, the patient may have a lesion in the right optic tract which leads to a deficit in the left half of the visual field of both eyes. This failure is referred to as bilateral homonymous hemianopsia (left). A lesion of the left optic tract would lead to a corresponding opposite deficit in the right half of the visual field. Depending on where the optic tract is damaged, this may lead to a complete or an incomplete deficit. Once such deficits have arisen, they do not usually disappear.

Further lesions can arise in the realm of visual radiation, and such lesions have diverse consequences since visual radiation spreads a fan-like manner. Tumors and strokes are the most frequent triggers for this visual disorder.

Deficits in the visual field can be observed in the following form:

- First: Pathology to the right part of the visual radiation produces left homonymous hemianopsia

- Second: Pathology to the leftward side of the visual radiation produces right homonymous hemianopsia

Quadrantanopsia occurs whenever there is only partial damage to the visual radiation such that a quadrant of the visual field is missing rather than an entire half.

Deficits in the upper part of the visual radiation are more severe than in the lower part. Deficits in the area of the visual radiation likewise do not regress either.

Amaurosis

This term refers to a complete loss of vision without apparent lesions in the eye; it can occur in 1 or 2 eyes. Amaurosis can be congenital (Leber’s congenital amaurosis) or secondary. What this means for the optic nerve is that injury is commonly secondary to compression of the nerve by tumor (commonly from the pituitary), trauma, or ischemic events.

Summary of the Important Diseases of All 12 Pairs of Cranial Nerves

Olfactory nerve (I)

- Anosmia (inability to smell)

- Hyposmia (weakened ability to smell)

Optical nerve (II)

- Anopsia or amaurosis (blindness in 1 or both eyes)

- Hemianopsia

- Quadrant anopsia

- Blinker-phenomenon

- Papilledema

Oculomotor nerve (III)

- Anisocoria (unequally wide pupils)

- Miosis (narrow pupils)

- Mydriasis (wide pupils)

- Gaze palsy

- Diplopia (double vision)

- Ptosis (drooping upper eyelid)

Trochlear nerve (IV)

- Strabismus

- Diplopia

Trigeminal nerve (V)

- Trigeminal neuralgia/tic doulourex

- Paresis of the muscles of mastication

- Loss of the sensation of touch and temperature

Abducens nerve (VI)

- Diplopia

Facial nerve (VII)

- Bell’s palsy (paralysis of the the facial muscles)

- Hyperacusis (sounds are perceived too loud)

- Loss of gustatory sensation in the anterior tongue

- Burning eye sensation due to dehydration of the conjunctiva/cornea

Vestibulocochlear nerve (VIII)

- Hypacusis (hearing loss)

- Deafness

- Tinnitus (permanent aural noises)

- Ataxia (instability regarding movement)

- Rotatory vertigo

- Nystagmus (eye twitching)

Glossopharyngeal nerve (IX)

- Difficulty swallowing

- Diminished salivation

- Loss of gustatory sensation in the posterior part of the tongue

- Loss of sensation in the throat

Vagus nerve (X)

- Hoarseness

- Difficulties with swallowing and at phonation

- Posticus paralysis (severe respiratory distress when a particular muscle of the larynx fails)

- Changes in heart rate (quicker or slower)

- Less gastric acid and intestinal peristalsis

Accessory nerve (XI)

- Inability to lift the shoulder

- Weakness in turning the head

The hypoglossal nerve (XII)

- Speech disorders

- Difficulty swallowing

Cranial nerve examination frequently appears in OSCEs. You’ll be expected to assess a subset of the twelve cranial nerves and identify abnormalities using your clinical skills. This cranial nerve examination OSCE guide provides a clear step-by-step approach to examining the cranial nerves, with an included video demonstration.

Cranial Nerves – Test and Examination

Gather equipment

Gather the appropriate equipment to perform cranial nerve examination:

- Pen torch

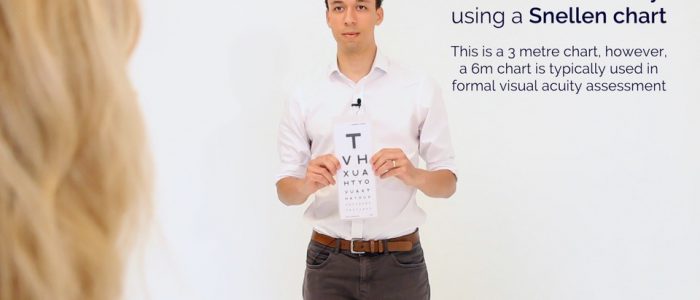

- Snellen chart

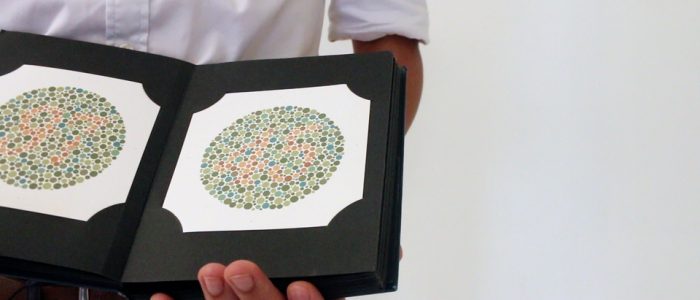

- Ishihara plates

- Ophthalmoscope and mydriatic eye drops (if necessary)

- Cotton wool

- Neuro-tip

- Tuning fork (512hz)

- Glass of water

Introduction

Wash your hands and don PPE if appropriate.

Introduce yourself to the patient including your name and role.

Confirm the patient’s name and date of birth.

Briefly explain what the examination will involve using patient-friendly language.

Gain consent to proceed with the examination.

Ask the patient to sit on a chair, approximately one arm’s length away.

Ask the patient if they have any pain before proceeding with the clinical examination.

General inspection

Perform a brief general inspection of the patient, looking for clinical signs suggestive of underlying pathology:

- Speech abnormalities: may indicate glossopharyngeal or vagus nerve pathology.

- Facial asymmetry: suggestive of facial nerve palsy.

- Eyelid abnormalities: ptosis may indicate oculomotor nerve pathology.

- Pupillary abnormalities: mydriasis occurs in oculomotor nerve palsy.

- Strabismus: may indicate oculomotor, trochlear or abducens nerve palsy.

- Limbs: pay attention to the patient’s arms and legs as they enter the room and take a seat noting any abnormalities (e.g. spasticity, weakness, wasting, tremor, fasciculation) which may suggest the presence of a neurological syndrome).

Look for objects or equipment on or around the patient that may provide useful insights into their medical history and current clinical status:

- Walking aids: gait issues are associated with a wide range of neurological pathology including Parkinson’s disease, stroke, cerebellar disease and myasthenia gravis.

- Hearing aids: often worn by patients with vestibulocochlear nerve issues (e.g. Ménière’s disease).

- Visual aids: the use of visual prisms or occluders may indicate underlying strabismus.

- Prescriptions: prescribing charts or personal prescriptions can provide useful information about the patient’s recent medications.

Olfactory nerve (CN I)

The olfactory nerve (CN I) transmits sensory information about odors to the central nervous system where they are perceived as smell (olfaction). There is no motor component to the olfactory nerve.

Ask the patient if they have noticed any recent changes to their sense of smell.

Olfaction can be tested more formally using different odors (e.g. lemon, peppermint), or most formally using the University of Pennsylvania smell identification test. However, this is unlikely to be required in an OSCE.

Causes of anosmia

There are many potential causes of anosmia including:

- Mucous blockage of the nose: preventing odors from reaching the olfactory nerve receptors.

- Head trauma: can result in shearing of the olfactory nerve fibers leading to anosmia.

- Genetics: some individuals have congenital anosmia.

- Parkinson’s disease: anosmia is an early feature of Parkinson’s disease.

- COVID-19: transient anosmia is a common feature of COVID-19.

Optic nerve (CN II)

The optic nerve (CN II) transmits sensory visual information from the retina to the brain. There is no motor component to the optic nerve.

Inspect the pupils

The pupil is the hole in the centre of the iris that allows light to enter the eye and reach the retina.

Assess pupil size:

- Normal pupil size varies between individuals and depends on lighting conditions (i.e. smaller in bright light, larger in the dark).

- Pupils are usually smaller in infancy and larger in adolescence.

Assess pupil shape:

- Pupils should be round, abnormal shapes can be congenital or due to pathology (e.g. posterior synechiae associated with uveitis).

- Peaked pupils in the context of trauma are suggestive of globe injury.

Assess pupil symmetry:

- Note any asymmetry in pupil size between the pupils (anisocoria). This may be longstanding and non-pathological or relate to actual pathology. If the pupil is more pronounced in bright light this would suggest that the larger pupil is the abnormal pupil, if more pronounced in dark this would suggest the smaller pupil is abnormal.

- Examples of asymmetry include a large pupil in oculomotor nerve palsy and a small and reactive pupil in Horner’s syndrome.

Visual acuity

Assessment of visual acuity (distance)

Begin by assessing the patient’s visual acuity using a Snellen chart. If the patient normally uses distance glasses, ensure these are worn for the assessment.

1. Stand the patient at 6 metres from the Snellen chart.

2. Ask the patient to cover one eye and read the lowest line they are able to.

3. Record the lowest line the patient was able to read (e.g. 6/6 (metric) which is equivalent to 20/20 (imperial)).

4. You can have the patient read through a pinhole to see if this improves vision (if vision is improved with a pinhole, it suggests there is a refractive component to the patient’s poor vision).

5. Repeat the above steps with the other eye.

Recording visual acuity

Visual acuity is recorded as chart distance (numerator) over the number of the lowest line read (denominator).

If the patient reads the 6/6 line but gets 2 letters incorrect, you would record as 6/6 (-2).

If the patient gets more than 2 letters wrong, then the previous line should be recorded as their acuity.

When recording the vision it should state whether this vision was unaided (UA), with glasses or with pinhole (PH).

Further steps for patients with poor vision

If the patient is unable to read the top line of the Snellen chart at 6 metres (even with pinhole) move through the following steps as necessary:

1. Reduce the distance to 3 metres from the Snellen chart (the acuity would then be recorded as 3/denominator).

2. Reduce the distance to 1 metre from the Snellen chart (1/denominator).

3. Assess if they can count the number of fingers you’re holding up (recorded as “Counting Fingers” or “CF”).

4. Assess if they can see gross hand movements (recorded as “Hand Movements” or “HM”).

5. Assess if they can detect light from a pen torch shone into each eye (“Perception of Light”/”PL” or “No Perception of Light”/”NPL”).

Causes of decreased visual acuity

Decreased visual acuity has many potential causes including:

- Refractive errors

- Amblyopia

- Ocular media opacities such as cataract or corneal scarring

- Retinal diseases such as age-related macular degeneration

- Optic nerve (CN II) pathology such as optic neuritis

- Lesions higher in the visual pathways

Optic nerve (CN II) pathology usually causes a decrease in acuity in the affected eye. In comparison, papilloedema (optic disc swelling from raised intracranial pressure), does not usually affect visual acuity until it is at a late stage.

Pupillary reflexes

With the patient seated, dim the lights in the assessment room to allow you to assess pupillary reflexes effectively.

Direct pupillary reflex

Assess the direct pupillary reflex:

- Shine the light from your pen torch into the patient’s pupil and observe for pupillary restriction in the ipsilateral eye.

- A normal direct pupillary reflex involves constriction of the pupil that the light is being shone into.

Consensual pupillary reflex

Assess the consensual pupillary reflex:

- Once again shine the light from your pen torch into the same pupil, but this time observe for pupillary restriction in the contralateral eye.

- A normal consensual pupillary reflex involves the contralateral pupil constricting as a response to light entering the eye being tested.

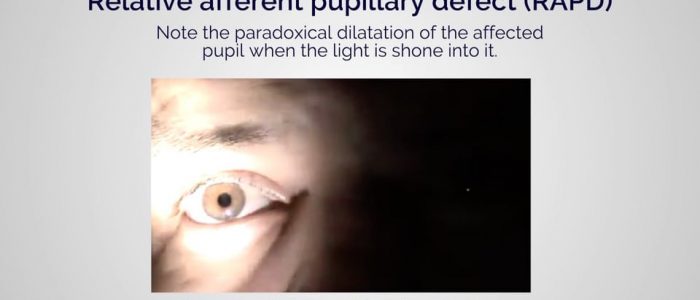

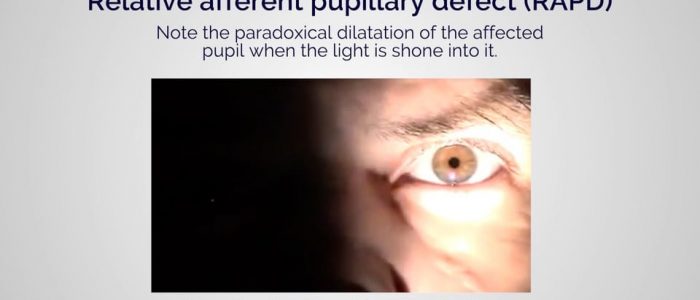

Swinging light test

Move the pen torch rapidly between the two pupils to check for a relative afferent pupillary defect (see more details below).

Accommodation reflex

1. Ask the patient to focus on a distant object (clock on the wall/light switch).

2. Place your finger approximately 20-30cm in front of their eyes (alternatively, use the patient’s own thumb).

3. Ask the patient to switch from looking at the distant object to the nearby finger/thumb.

4. Observe the pupils, you should see constriction and convergence bilaterally.

Pupillary light reflex

Each afferent limb of the pupillary reflex has two efferent limbs, one ipsilateral and one contralateral.

The afferent limb functions as follows:

- Sensory input (e.g. light being shone into the eye) is transmitted from the retina, along the optic nerve to the ipsilateral pretectal nucleus in the midbrain.

The two efferent limbs function as follows:

- Motor output is transmitted from the pretectal nucleus to the Edinger-Westphal nuclei on both sides of the brain (ipsilateral and contralateral).

- Each Edinger-Westphal nucleus gives rise to efferent nerve fibres which travel in the oculomotor nerve to innervate the ciliary sphincter and enable pupillary constriction.

Normal pupillary light reflexes rely on the afferent and efferent pathways of the reflex arc being intact and therefore provide an indirect way of assessing their function:

- The direct pupillary reflex assesses the ipsilateral afferent limb and the ipsilateral efferent limb of the pathway.

- The consensual pupillary reflex assesses the contralateral efferent limb of the pathway.

- The swinging light test is used to detect relative afferent limb defects.

Abnormal pupillary responses

- Relative afferent pupillary defect (Marcus-Gunn pupil): normally light shone into either eye should constrict both pupils equally (due to the dual efferent pathways described above). When the afferent limb in one of the optic nerves is damaged, partially or completely, both pupils will constrict less when light is shone into the affected eye compared to the healthy eye. The pupils, therefore, appear to relatively dilate when swinging the torch from the healthy to the affected eye. This is termed a relative…. afferent… pupillary defect. This can be due to significant retinal damage in the affected eye secondary to central retinal artery or vein occlusion and large retinal detachment; or due to significant optic neuropathy such as optic neuritis, unilateral advanced glaucoma and compression secondary to tumour or abscess.

- Unilateral efferent defect: commonly caused by extrinsic compression of the oculomotor nerve, resulting in the loss of the efferent limb of the ipsilateral pupillary reflexes. As a result, the ipsilateral pupil is dilated and non-responsive to light entering either eye (due to loss of ciliary sphincter function). The consensual light reflex in the unaffected eye would still be present as the afferent pathway (i.e. optic nerve) of the affected eye and the efferent pathway (i.e. oculomotor nerve) of the unaffected eye remain intact.

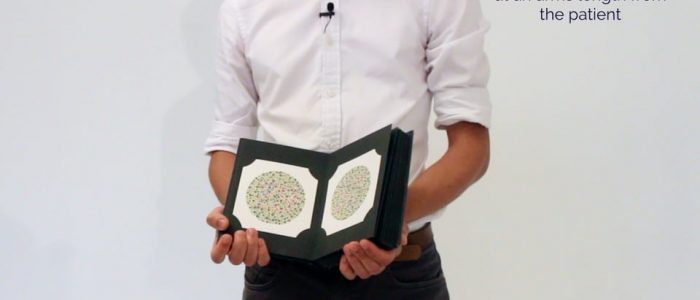

Colour vision assessment

Colour vision can be assessed using Ishihara plates, each of which contains a colored circle of dots. Within the pattern of each circle are dots that form a number or shape that is clearly visible to those with normal color vision and difficult or impossible to see for those with a red-green color vision defect.

How to use Ishihara plates

If the patient normally wears glasses for reading, ensure these are worn for the assessment.

1. Ask the patient to cover one of their eyes.

2. Then ask the patient to read the numbers on the Ishihara plates. The first page is usually the ‘test plate’ which does not test color vision and instead assesses contrast sensitivity. If the patient is unable to read the test plate, you should document this.

3. If the patient is able to read the test plate, you should move through all of the Ishihara plates, asking the patient to identify the number on each. Once the test is complete, you should document the number of plates the patient identified correctly, including the test plate (e.g. 13/13).

4. Repeat the assessment on the other eye.

Colour vision deficiencies

Colour vision deficiencies can be congenital or acquired. Some causes of acquired colour vision deficiency include:

- Optic neuritis: results in a reduction of colour vision (typically red).

- Vitamin A deficiency

- Chronic solvent exposure

Visual neglect/inattention

Visual neglect (also known as visual inattention) is a condition in which an individual develops a deficit in their awareness of one side of their visual field. This typically occurs in the context of parietal lobe injury after stroke, which results in an inability to perceive or process stimuli on one side of the body. The side of the visual field that is affected is contralateral to the location of the parietal lesion. It should be noted that visual neglect is not caused by optic nerve pathology and therefore this test is often not included in a cranial nerve exam.

Assessment

To assess for visual neglect:

1. Position yourself sitting opposite the patient approximately 1 metre away.

2. Ask the patient to remain focused on a fixed point on your face (e.g. nose) and to state if they see your left, right or both hands moving.

3. Hold your hands out laterally with each occupying one side of the patient’s visual field (i.e. left and right).

4. Take turns wiggling a finger on each hand to see if the patient is able to correctly identify which hand has moved.

5. Finally wiggle both fingers simultaneously to see if the patient is able to correctly identify this (often patients with visual neglect will only report the hand moving in the unaffected visual field – i.e. ipsilateral to the primary brain lesion).

Visual fields

This method of assessment relies on comparing the patient’s visual field with your own and therefore for it to work:

- you need to position yourself, the patient and the target correctly (see details below).

- you need to have normal visual fields and a normal-sized blindspot.

Visual field assessment

1. Sit directly opposite the patient, at a distance of around 1 metre.

2. Ask the patient to cover one eye with their hand.

3. If the patient covers their right eye, you should cover your left eye (mirroring the patient).

4. Ask the patient to focus on part of your face (e.g. nose) and not move their head or eyes during the assessment. You should do the same and focus your gaze on the patient’s face.

5. As a screen for central visual field loss or distortion, ask the patient if any part of your face is missing or distorted. A formal assessment can be completed with an Amsler chart.

6. Position the hatpin (or another visual target such as your finger) at an equal distance between you and the patient (this is essential for the assessment to work).

7. Assess the patient’s peripheral visual field by comparing to your own and using the target. Start from the periphery and slowly move the target towards the centre, asking the patient to report when they first see it. If you are able to see the target but the patient cannot, this would suggest the patient has a reduced visual field.

8. Repeat this process for each visual field quadrant, then repeat the entire process for the other eye.

9. Document your findings.

Types of visual field defects

- Bitemporal hemianopia: loss of the temporal visual field in both eyes resulting in central tunnel vision. Bitemporal hemianopia typically occurs as a result of optic chiasm compression by a tumour (e.g. pituitary adenoma, craniopharyngioma).

- Homonymous field defects: affect the same side of the visual field in each eye and are commonly attributed to stroke, tumour, abscess (i.e. pathology affecting visual pathways posterior to the optic chiasm). These are deemed hemianopias if half the vision is affected and quadrantanopias if a quarter of the vision is affected.

- Scotoma: an area of absent or reduced vision surrounded by areas of normal vision. There is a wide range of possible aetiologies including demyelinating disease (e.g. multiple sclerosis) and diabetic maculopathy.

- Monocular vision loss: total loss of vision in one eye secondary to optic nerve pathology (e.g. anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy) or ocular diseases (e.g. central retinal artery occlusion, total retinal detachment).

Blind spot

A physiological blind spot exists in all healthy individuals as a result of the lack of photoreceptor cells in the area where the optic nerve passes through the optic disc. In day to day life, the brain does an excellent job of reducing our awareness of the blind spot by using information from other areas of the retina and the other eye to mask the defect.

Blind spot assessment

1. Sit directly opposite the patient, at a distance of around 1 metre.

2. Ask the patient to cover one eye with their hand.

3. If the patient covers their right eye, you should cover your left eye (mirroring the patient).

4. Ask the patient to focus on part of your face (e.g. nose) and not move their head or eyes during the assessment. You should do the same and focus your gaze on the patient’s face.

5. Using a red hatpin (or alternatively, a cotton bud stained with fluorescein/pen with a red base) start by identifying and assessing the patient’s blind spot in comparison to the size of your own. The red hatpin needs to be positioned at an equal distance between you and the patient for this to work.

6. Ask the patient to say when the red part of the hatpin disappears, whilst continuing to focus on the same point on your face.

7. With the red hatpin positioned equidistant between you and the patient, slowly move it laterally until the patient reports the disappearance of the top of the hatpin. The blind spot is normally found just temporal to central vision at eye level. The disappearance of the hatpin should occur at a similar point for you and the patient.

8. After the hatpin has disappeared for the patient, continue to move it laterally and ask the patient to let you know when they can see it again. The point at which the patient reports the hatpin re-appearing should be similar to the point at which it re-appears for you (presuming the patient and you have a normal blind spot).

9. You can further assess the superior and inferior borders of the blind spot using the same process.

Fundoscopy

In the context of a cranial nerve examination, fundoscopy is performed to assess the optic disc for signs of pathology (e.g. papilloedema). You should offer to perform fundoscopy in your OSCE, however, it may not be required. See our dedicated fundoscopy guide for more details.

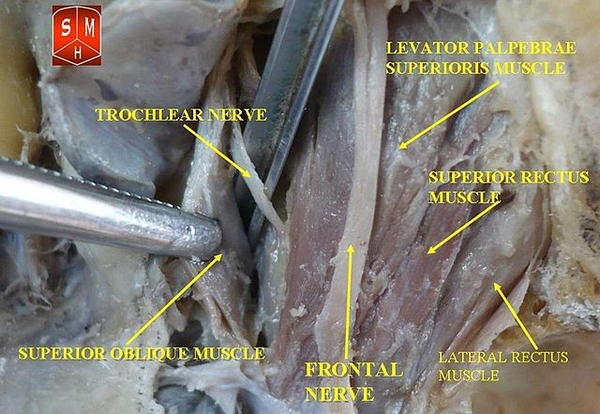

Oculomotor (CN III), trochlear (CN IV) and abducens (CN VI) nerves

The oculomotor (CN III), trochlear (CN IV) and abducens (CN VI) nerves transmit motor information to the extraocular muscles to control eye movement and eyelid function. The oculomotor nerve also carries parasympathetic fibres responsible for pupillary constriction.

Eyelids

Inspect the eyelids for evidence of ptosis which can be associated with:

- Oculomotor nerve pathology

- Horner’s syndrome

- Neuromuscular pathology (e.g. myasthenia gravis)

Eye movements

Briefly assess for abnormalities of eye movements which may be caused by underlying cranial nerve palsy (e.g. oculomotor, trochlear, abducens, vestibular nerve pathology).

1. Hold your finger (or a pin) approximately 30cm in front of the patient’s eyes and ask them to focus on it. Look at the eyes in the primary position for any deviation or abnormal movements.

2. Ask the patient to keep their head still whilst following your finger with their eyes. Ask them to let you know if they experience any double vision or pain.

3. Move your finger through the various axes of eye movement in a ‘H’ pattern.

4. Observe for any restriction of eye movement and note any nystagmus (which may suggest vestibular nerve pathology or stroke).

Actions of the extraocular muscles

- Superior rectus: primary action is elevation, secondary actions include adduction and medial rotation of the eyeball.

- Inferior rectus: primary action is depression, secondary actions include adduction and lateral rotation of the eyeball.

- Medial rectus: adduction of the eyeball.

- Lateral rectus: abduction of the eyeball.

- Superior oblique: depresses, abducts and medially rotates the eyeball.

- Inferior oblique: elevates, abducts and laterally rotates the eyeball.

Oculomotor, trochlear and abducens nerve palsy

Damage to any of the three cranial nerves innervating the extraocular muscles can result in paralysis of the corresponding muscles.

Oculomotor nerve palsy (CN III)

The oculomotor nerve supplies all extraocular muscles except the superior oblique (CNIV) and the lateral rectus (CNVI). Oculomotor palsy (a.k.a. ‘third nerve palsy’), therefore, results in the unopposed action of both the lateral rectus and superior oblique muscles, which pull the eye inferolateral. As a result, patients typically present with a ‘down and out’ appearance of the affected eye.

Oculomotor nerve palsy can also cause ptosis (due to a loss of innervation to levator palpebrae superioris) as well as mydriasis due to the loss of parasympathetic fibres responsible for innervating to the sphincter pupillae muscle.

Trochlear nerve palsy (CN IV)

The only muscle the trochlear nerve innervates is the superior oblique muscle. As a result, trochlear nerve palsy (‘fourth nerve palsy’) typically results in vertical diplopia when looking inferiorly, due to loss of the superior oblique’s action of pulling the eye downwards. Patients often try to compensate for this by tilting their heads forwards and tucking their chin in, which minimises vertical diplopia. Trochlear nerve palsy also causes torsional diplopia (as the superior oblique muscle assists with intorsion of the eye as the head tilts). To compensate for this, patients with trochlear nerve palsy tilt their head to the opposite side, in order to fuse the two images together.

Abducens nerve palsy (CN VI)

The abducens nerve (CN VI) innervates the lateral rectus muscle. Abducens nerve palsy (‘sixth nerve palsy’) results in unopposed adduction of the eye (by the medial rectus muscle), resulting in a convergent squint. Patients typically present with horizontal diplopia which is worsened when they attempt to look towards the affected side.

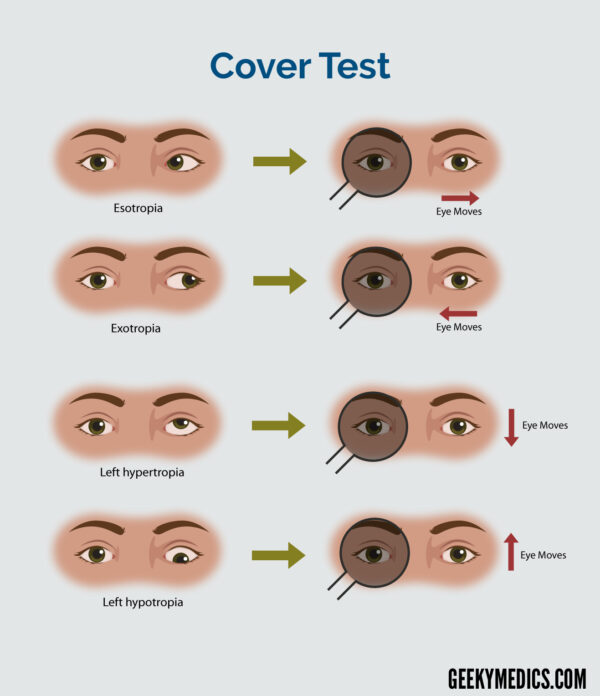

Assessment of strabismus

Strabismus is a condition in which the eyes do not properly align with each other when looking at an object. Pathology affecting the oculomotor, trochlear or abducens nerves can cause strabismus.

Light reflex test (a.k.a. corneal reflex test or Hirschberg test)

1. Ask the patient to focus on a target approximately half a metre away whilst you shine a pen torch towards both eyes.

2. Inspect the corneal reflex on each eye:

- If the ocular alignment is normal, the light reflex will be positioned centrally and symmetrically in each pupil.

- Deflection of the corneal light reflex in one eye suggests a misalignment.

Cover test

The cover test is used to determine if a heterotropia (i.e. manifest strabismus) is present.

1. Ask the patient to fixate on a target (e.g. light switch).

2. Occlude one of the patient’s eyes and observe the contralateral eye for a shift in fixation:

- If there is no shift in fixation in the contralateral eye, while covering either eye, the patient is orthotropic (i.e. normal alignment).

- If there is a shift in fixation in the contralateral eye, while covering the other eye, the patient has a heterotropia.

3. Repeat the cover test on the other eye.

The direction of the shift in fixation determines the type of tropia; the table below describes the appropriate interpretation.

Interpretation of the cover test

| Direction of eye at rest | The direction of shift in fixation of the unoccluded eye when the opposite eye is occluded | Type of tropia present |

| Temporally (i.e. laterally or outwards) | Nasally (i.e. medially or inwards) | Exotropia |

| Nasally (i.e. medially or inwards) | Temporally (i.e. laterally or outwards) | Esotropia |

| Superiorly (i.e. upwards) | Inferiorly (i.e. downwards) | Hypertropia |

| Inferiorly (i.e. downwards) | Superiorly (i.e. upwards) | Hypotropia |

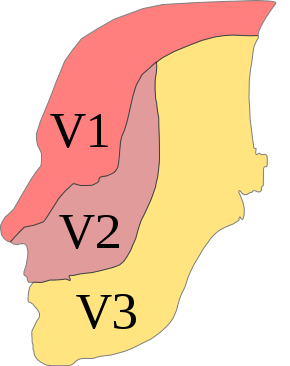

Trigeminal nerve (CN V)

The trigeminal nerve (CN V) transmits both sensory information about facial sensation and motor information to the muscles of mastication.

The trigeminal nerve has three sub-divisions, each of which has its own broad set of functions (not all are covered below):

- Ophthalmic (V1): carries sensory information from the scalp and forehead, nose, upper eyelid as well as the conjunctiva and cornea of the eye.

- Maxillary (V2): carries sensory information from the lower eyelid, cheek, nares, upper lip, upper teeth and gums.

- Mandibular (V3): carries sensory information from the chin, jaw, lower lip, mouth, lower teeth and gums. Also carries motor information to the muscles of mastication (masseter, temporal muscle and the medial/lateral pterygoids) as well as the tensor tympani, tensor veli palatini, mylohyoid and digastric muscles.

Sensory assessment

First, explain the modalities of sensation you are going to assess (e.g. light touch/pinprick) to the patient by demonstrating on their sternum. This provides them with a reference of what the sensation should feel like (assuming they have no sensory deficits in the region overlying the sternum).

Ask the patient to close their eyes and say ‘yes’ each time they feel you touch their face.

Assess the sensory component of V1, V2 and V3 by testing light touch and pinprick sensation across regions of the face supplied by each branch:

- Forehead (lateral aspect): ophthalmic (V1)

- Cheek: maxillary (V2)

- Lower jaw (avoid the angle of the mandible as it is supplied by C2/C3): mandibular branch (V3)

You should compare each region on both sides of the face to allow the patient to identify subtle differences in sensation.

Motor assessment

Use the muscles of mastication to assess the motor component of V3:

1. Inspect the temporalis (located in the temple region) and masseter muscles (located at the posterior jaw) for evidence of wasting. This is typically most noticeable in the temporalis muscles, where a hollowing effect in the temple region is observed.

2. Palpate the masseter muscle (located at the posterior jaw) bilaterally whilst asking the patient to clench their teeth to allow you to assess and compare muscle bulk.

3. Ask the patient to open their mouth whilst you apply resistance underneath the jaw to assess the lateral pterygoid muscles. An inability to open the jaw against resistance or deviation of the jaw (typically to the side of the lesion) may occur in trigeminal nerve palsy.

Reflexes

Jaw jerk reflex

The jaw jerk reflex is a stretch reflex that involves the slight jerking of the jaw upwards in response to a downward tap. This response is exaggerated in patients with an upper motor neuron lesion. Both afferent and efferent pathways of the jaw jerk reflex involve the trigeminal nerve.

To assess the jaw jerk reflex:

1. Clearly explain what the procedure will involve to the patient and gain consent to proceed.

2. Ask the patient to open their mouth.

3. Place your finger horizontally across the patient’s chin.

4. Tap your finger gently with the tendon hammer.

5. In healthy individuals, this should trigger a slight closure of the mouth. In patients with upper motor neuron lesions, the jaw may briskly move upwards causing the mouth to close completely.

Corneal reflex

The corneal reflex involves involuntary blinking of both eyelids in response to unilateral corneal stimulation (direct and consensual blinking). The afferent branch of the corneal reflex involves V1 of the trigeminal nerve whereas the efferent branch is mediated by the temporal and zygomatic branches of the facial nerve.

To assess the corneal reflex:

1. Clearly explain what the procedure will involve to the patient and gain consent to proceed.

2. Gently touch the edge of the cornea using a wisp of cotton wool.

3. In healthy individuals, you should observe both direct and consensual blinking. The absence of a blinking response suggests pathology involving either the trigeminal or facial nerve.

The corneal reflex is not usually assessed in an OSCE scenario, however, you should offer to test it and understand the purpose behind the test.

Facial nerve (CN VII)

The facial nerve (CN VII) transmits motor information to the muscles of facial expression and the stapedius muscle (involved in the regulation of hearing). The facial nerve also has a sensory component responsible for the conveyance of taste from the anterior two-thirds of the tongue.

Sensory assessment

Ask the patient if they have noticed any recent changes in their sense of taste.

Motor assessment

Hearing changes

Ask the patient if they have noticed any changes to their hearing (paralysis of the stapedius muscle can result in hyperacusis).

Inspection

Inspect the patient’s face at rest for asymmetry, paying particular attention to:

- Forehead wrinkles

- Nasolabial folds

- Angles of the mouth

Facial movement

Ask the patient to carry out a sequence of facial expressions whilst again observing for asymmetry:

- Raised eyebrows: assesses frontalis – “Raise your eyebrows as if you’re surprised.”

- Closed eyes: assesses orbicular oculi – “Scrunch up your eyes and don’t let me open them.”

- Blown out cheeks: assesses orbicularis oris – “Blow out your cheeks and don’t let me deflate them.”

- Smiling: assesses levator anguli oris and zygomaticus major – “Can you do a big smile for me?”

- Pursed lips: assesses orbicularis oris and buccinator – “Can you try to whistle?”

Facial nerve palsy

Facial nerve palsy presents with unilateral weakness of the muscles of facial expression and can be caused by both upper and lower motor neuron lesions.

Facial nerve palsy caused by a lower motor neuron lesion presents with weakness of all ipsilateral muscles of facial expression, due to the loss of innervation to all muscles on the affected side. The most common cause of lower motor neuron facial palsy is Bell’s palsy.

Facial nerve palsy caused by an upper motor neuron lesion also presents with unilateral facial muscle weakness, however, the upper facial muscles are partially spared because of bilateral cortical representation (resulting in forehead/frontalis function being somewhat maintained). The most common cause of upper motor neuron facial palsy is stroke.

Vestibulocochlear nerve (CN VIII)

The vestibulocochlear nerve (CN VIII) transmits sensory information about sound and balance from the inner ear to the brain. The vestibulocochlear nerve has no motor component.

Gross hearing assessment

Preparation

Ask the patient if they have noticed any change in their hearing recently.

Explain that you’re going to say 3 words or 3 numbers and you’d like the patient to repeat them back to you (choose two-syllable words or bi-digit numbers).

Assessment

1. Position yourself approximately 60cm from the ear and then whisper a number or word.

2. Mask the ear not being tested by rubbing the tragus. Do not place your arm across the face of the patient when rubbing the tragus, it is far nicer to occlude the ear from behind the head. If possible shield the patient’s eyes to prevent any visual stimulus.

3. Ask the patient to repeat the number or word back to you. If they get two-thirds or more correct then their hearing level is 12db or better. If there is no response use a conversational voice (48db or worse) or loud voice (76db or worse).

4. If there is no response you can move closer and repeat the test at 15cm. Here the thresholds are 34db for a whisper and 56db for a conversational voice.

5. Assess the other ear in the same way.

Rinne’s test

1. Place a vibrating 512 Hz tuning fork firmly on the mastoid process (apply pressure to the opposite side of the head to make sure the contact is firm). This tests bone conduction.

2. Confirm the patient can hear the sound of the tuning fork and then ask them to tell you when they can no longer hear it.

3. When the patient can no longer hear the sound, move the tuning fork in front of the external auditory meatus to test air conduction.

4. Ask the patient if they can now hear the sound again. If they can hear the sound, it suggests air conduction is better than bone conduction, which is what would be expected in a healthy individual (this is often confusingly referred to as a “Rinne’s positive” result).

Summary of Rinne’s test results

These results should be assessed in context with the results of Weber’s test before any diagnostic assumptions are made:

- Normal result: air conduction > bone conduction (Rinne’s positive)

- Sensorineural deafness: air conduction > bone conduction (Rinne’s positive) – due to both air and bone conduction being reduced equally

- Conductive deafness: bone conduction > air conduction (Rinne’s negative)

Weber’s test

1. Tap a 512Hz tuning fork and place in the midline of the forehead. The tuning fork should be set in motion by striking it on your knee (not the patient’s knee or a table).

2. Ask the patient “Where do you hear the sound?”

These results should be assessed in context with the results of Rinne’s test before any diagnostic assumptions are made:

- Normal: sound is heard equally in both ears.

- Sensorineural deafness: sound is heard louder on the side of the intact ear.

- Conductive deafness: sound is heard louder on the side of the affected ear.

A 512Hz tuning fork is used as it gives the best balance between time of decay and tactile vibration. Ideally, you want a tuning fork that has a long period of decay and cannot be detected by vibration sensation.

Conductive vs sensorineural hearing loss

Conductive hearing loss occurs when sound is unable to effectively transfer at any point between the outer ear, external auditory canal, tympanic membrane and middle ear (ossicles). Causes of conductive hearing loss include excessive ear wax, otitis externa, otitis media, perforated tympanic membrane and otosclerosis.

Sensorineural hearing loss occurs due to dysfunction of the cochlea and/or vestibulocochlear nerve. Causes of sensorineural hearing loss include increasing age (presbycusis), excessive noise exposure, genetic mutations, viral infections (e.g. cytomegalovirus) and ototoxic agents (e.g. gentamicin).

Vestibular testing – “Unterberger” or “Turning test”

Ask the patient to march on the spot with their arms outstretched and their eyes closed:

- Normal result: the patient remains in the same position.

- Vestibular lesion: the patient will turn towards the side of the lesion

Vestibular testing – “Head thrust test” or “Vestibular-ocular reflex”

Before performing this test you need to check if the patient has any neck problems and if so you should not proceed.

1. Explain to the patient that the test will involve briskly turning their head and then gain consent to proceed.

2. Sit facing the patient and ask them to fixate on your nose at all times during the test.

3. Hold their head in your hands (one hand covering each ear) and rotate it rapidly to the left, at a medium amplitude.

4. Repeat this process, but this time turn the head to the right.

The normal response is that ocular fixation is maintained. In a patient with loss of vestibular function on one side, the eyes will first move in the direction of the head (losing fixation), before a corrective refixation saccade occurs towards your nose.

Glossopharyngeal (CN IX) and vagus (CN X) nerves

The glossopharyngeal nerve transmits motor information to the stylopharyngeus muscle which elevates the pharynx during swallowing and speech. The glossopharyngeal nerve also transmits sensory information that conveys taste from the posterior third of the tongue. Visceral sensory fibres of CN IX also mediate the afferent limb of the gag reflex.

The vagus nerve transmits motor information to several muscles of the mouth which are involved in the production of speech and the efferent limb of the gag reflex.

The glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves are assessed together because of their closely related functions.

Assessment

Ask the patient if they have experienced any issues with swallowing, as well as any changes to their voice or cough.

Inspection

Ask the patient to open their mouth and inspect the soft palate and uvula:

- Note the position of the uvula. Vagus nerve lesions result in deviation of the uvula towards the unaffected side.

Ask the patient to say “ahh“:

- Inspect the palate and uvula which should elevate symmetrically, with the uvula remaining in the midline. A vagus nerve lesion will cause asymmetrical elevation of the palate and uvula deviation away from the lesion.

Ask the patient to cough:

- Vagus nerve lesions can result in the presence of a weak, non-explosive sounding bovine cough caused by an inability to close the glottis.

Swallow assessment

Ask the patient to take a small sip of water (approximately 3 teaspoons) and observe the patient swallow. The presence of a cough or a change to the quality of their voice suggests an ineffective swallow which can be caused by both glossopharyngeal (afferent) and vagus (efferent) nerve pathology.

Gag reflex

The gag reflex involves both the glossopharyngeal nerve (afferent) and the vagus nerve (efferent). This test is highly unpleasant for patients and therefore the swallow test mentioned previously is preferred as an alternative. You should not perform this test in an OSCE, although you may be expected to have an understanding of what cranial nerves are involved in the reflex.

To perform the gag reflex:

1. Stimulate the posterior aspect of the tongue and oropharynx which in healthy individuals should trigger a gag reflex. The absence of a gag reflex can be caused by both glossopharyngeal and vagus nerve pathology.

Accessory nerve (CN XI)

The accessory nerve (CN XI) transmits motor information to the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles. It does not have a sensory component.

Assessment

To assess the accessory nerve:

1. First, inspect for evidence sternocleidomastoid or trapezius muscle wasting.

2. Ask the patient to raise their shoulders and resist you pushing them downwards: this assesses the trapezius muscle (accessory nerve palsy will result in weakness).

3. Ask the patient to turn their head left whilst you resist the movement and then repeat with the patient turning their head to the right: this assesses the sternocleidomastoid muscle (accessory nerve palsy will result in weakness).

Hypoglossal nerve (CN XII)

The hypoglossal nerve (CN XII) transmits motor information to the extrinsic muscles of the tongue (except for palatoglossus which is innervated by the vagus nerve). It does not have a sensory component.

Assessment

To assess the hypoglossal nerve:

1. Ask the patient to open their mouth and inspect the tongue for wasting and fasciculations at rest (minor fasciculations can be normal).

2. Ask the patient to protrude their tongue and observe for any deviation (which occurs towards the side of a hypoglossal lesion).

3. Place your finger on the patient’s cheek and ask them to push their tongue against it. Repeat this on each cheek to assess and compare power (weakness would be present on the side of the lesion).

Hypoglossal nerve palsy

Hypoglossal nerve palsy causes atrophy of the ipsilateral tongue and deviation of the tongue when protruded towards the side of the lesion. This occurs due to the overaction of the functioning genioglossus muscle on the unaffected side of the tongue.

To complete the examination…

Explain to the patient that the examination is now finished.

Thank the patient for their time.

Dispose of PPE appropriately and wash your hands.

Summarise your findings.

References