Median Nerve Paralysis is often caused by deep, penetrating injuries to the arm, forearm, or wrist. It may also occur from blunt force trauma or neuropathy. Median nerve palsy can be separated into 2 subsections—high and low median nerve palsy. High MNP involves lesions at the elbow and forearm areas.

The median nerve also called the eye of the hand, is a mixed nerve with a role of primary importance in the functionality of the hand. It innervates the group of flexor-pronator muscles in the forearm and most of the musculature present in the radial portion of the hand, controlling abduction of the thumb, flexion of the hand at the wrist, flexion of the digital phalanx of the fingers. Again the nerve allows the sensory innervation to the flying face of the thumb, index, middle and radial side of the ring finger and the entire palmar region of the radial half of the hand. It also provides sensitivity to the dorsal skin of the last two phalanges of the index and middle fingers.

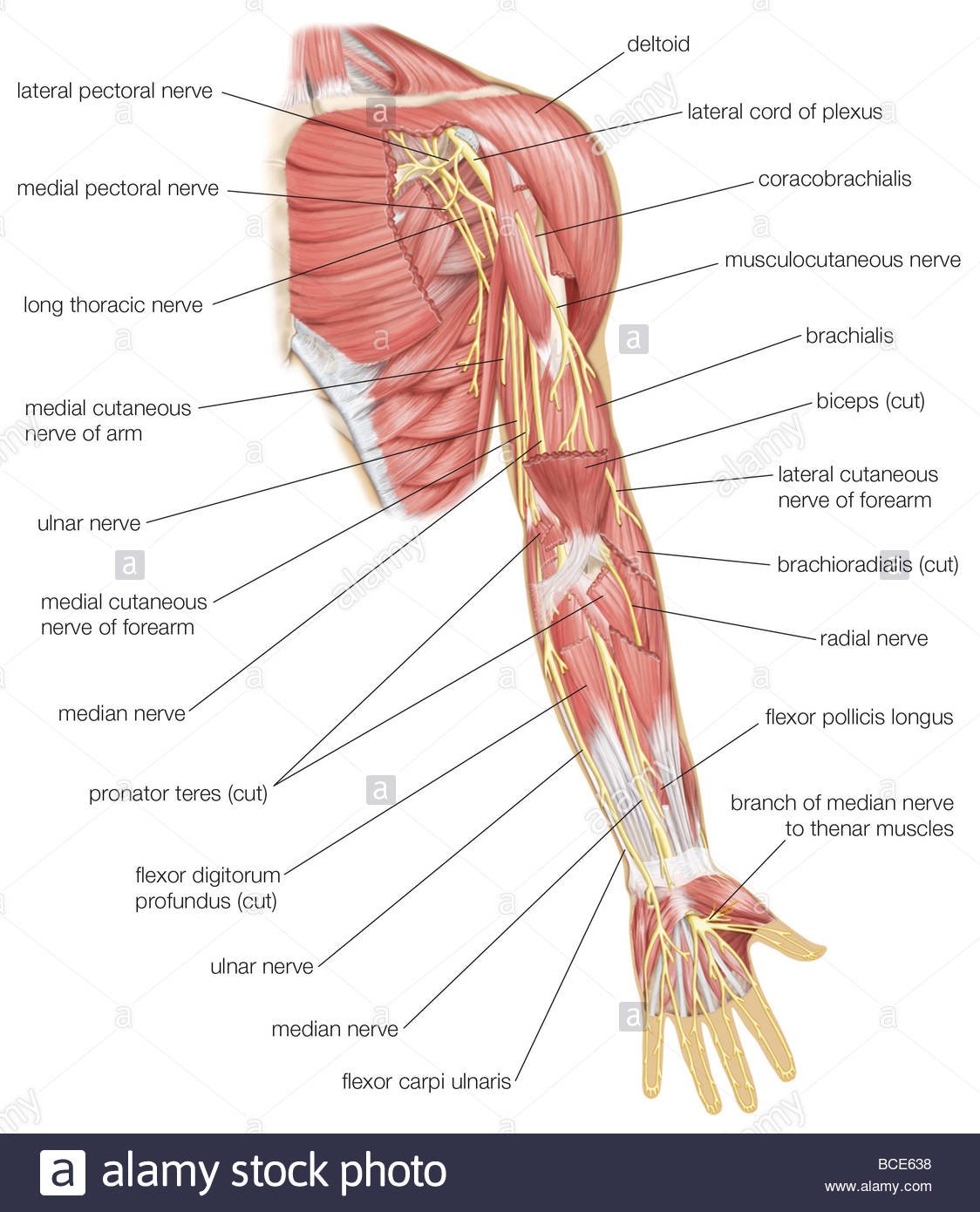

Anatomy of Median Nerve Palsy

Paralysis of flexor digitorum radialis will result in lateral deviation of the hand, loss of flexion at the interphalangeal joints due to paralysis of the flexor digitorum superficialis, and flexor digitorum profundus. Loss of flexion at the terminal phalanx of the thumb can occur due to the paralysis of flexor pollicis longus. The opponent pollicis is most likely to be lost due to the paralysis of the thenar muscles with associated wasted of the thenar muscles. The thumb is usually rotated and adducted and referred to as an “ape-like hand.”

“Pointing finger” deformity is caused due to injury to the median nerve in the mid-forearm by paralysis of flexor digitorum superficialis. Loss of general sensations over the lateral three and a half fingers over the palmar and dorsal surfaces of the hand can occur with median nerve injury. The area of the skin in median nerve injury can experience sensory loss, where the skin is warm and dry. In the case of long-standing vasomotor changes, the pulp of the fingers undergoes atrophic changes.

The median nerve receives fibers from roots C6, C7, C8, T1 and sometimes C5. It is formed in the axilla by a branch from the medial and lateral chords of the brachial plexus, which are on either side of the axillary artery and fuse together to create the nerve anterior to the artery.

The median nerve is closely related to the brachial artery within the arm. The nerve enters the cubital fossa medial to the brachialis tendon and passes between the two heads of the pronator teres. It then gives off the anterior interosseus branch in the pronator teres.

The nerve continues down the forearm between the flexor digitorum profundus and the flexor digitorum superficialis. The median nerve emerges to lie between the flexor digitorum superficialis and the flexor carpi ulnaris muscles which are just above the wrist. At this position, the nerve gives off the palmar cutaneous branch that supplies the skin of the central portion of the palm.

The nerve continues through the carpal tunnel into the hand, lying in the carpal tunnel anterior and lateral to the tendons of the flexor digitorum superficialis. Once in the hand, the nerve splits into a muscular branch and palmar digital branches. The muscular branch supplies the thenar eminence while the palmar digital branch supplies sensation to the palmar aspect of the lateral 3 ½ digits and the lateral two lumbricals.[rx]

Causes of Median Nerve Palsy

Median nerve injuries occur by multiple mechanisms and can become injured at different sites along its course in the upper limb. Quick and repetitive grasping or pronation movements (prolonged hammering, ladling food, cleaning dishes, tennis) may cause PT muscle hypertrophy and entrapment of MN, especially in those individuals who have additional fibrous brands.[rx]

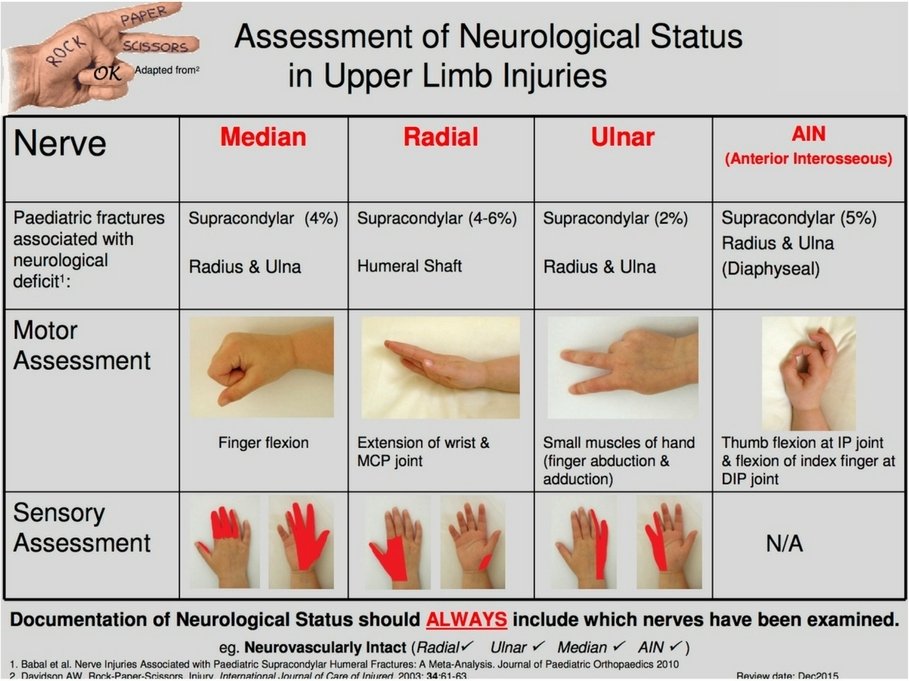

Common injuries to the median nerves include anterior shoulder dislocation, elbow dislocation, humerus fracture, midshaft radius fractures, stab wounds, prolonged placement of a tourniquet, and repeated use of crutches. However, these injuries are rarely in isolation, and often associated with radial or ulnar nerve neuropathies as well. The most common mechanisms of injury are listed below.

- Traumatic injury – of the arm such as humerus fractures can rarely cause paralysis of the median nerve, whereas an acute traumatic injury from a deep wound is more frequent. Stab wounds, stab wounds, gunshot wounds, high energy injuries such as road accidents, or more complex brachial plexus injuries can induce nerve lesion at the axilla, or upper. Damage at this level causes paralysis of all the innervated musculature of the median nerve and sensory impairment.

- Compression, stretch, or traumatic disruption – of the nerve may result in median nerve palsies. As noted, the key to providing appropriate care to patients with median nerve palsy is accurately identifying the source of nerve dysfunction through a careful physical examination and when needed, confirming injury with advanced diagnostic techniques.

- Penetrating injuries – to the upper arm can result in a median nerve palsy. Injuries to the median nerve at this location often result in a vascular injury given the nerve’s proximity to the brachial artery. Such an injury to the brachial artery will most often result in an under perfused extremity, constituting a vascular emergency. There have also been case reports of damage to the median nerve in the upper extremity after a brachial angiography.[rx][rx]

- The compression of the median nerve – can occur at multiple sites in and around the elbow. Median nerve impingement may occur at the ligament of Struthers and supracondylar process of the medial epicondyle, or slightly more distal at the bicipital aponeurosis as well as between the heads of pronator teres.[rx]

- Increased pressure within the carpal tunnel – leads to nerve compression and damage.[rx] Repetitive motion and the use of vibratory tools increase the risk of carpal tunnel. With forceful hand exertional, the most important factor in occupational-related carpal tunnel syndrome.[rx]

-

Direct trauma at the wrist and elbow joints

-

Accidental trauma during a surgical procedure in the axilla, wrist, and palm can damage the median nerve.

-

The nerve may become injured in attempted suicide.

-

Median nerve injury is associated with a fracture of the humerus, especially supracondylar fracture.

-

Entrapment at the elbow between the two heads of pronator teres (pronator teres syndrome) and under the flexor retinaculum (carpal tunnel syndrome)

-

The median nerve can be involved in generalized degenerative and demyelinating disorders

-

Neuropathy such as chemotherapy-induced peripheral chemotherapy[rx]

Symptoms of Median Nerve Palsy

- Lack of ability to abduct and oppose the thumb due to paralysis of the thenar muscles. This is called “ape-hand deformity”.[rx]

- Sensory loss in the thumbs, index fingers, long fingers, and the radial aspect of the ring fingers

- Weakness in forearm pronation and wrist and finger flexion[rx]

- Activities of daily living such as brushing teeth, tying shoes, making phone calls, turning doorknobs and writing, may become difficult with a median nerve injury.

- An injury above the elbow may result in difficulty or even inability to turn the hand over or flex the wrist down.

- Injuries below this may cause tingling or numbness in the forearm, thumb and the three adjacent fingers.

- A weakness with gripping and inability to move the thumb across the palm may also be experienced along with wasting of the muscles at the base of the thumb.

- Inability to abduct and oppose thumb (also called “ape-hand deformity”)

- Sensory loss or tingling in thumb and digits and radial aspect of ring fingers

- Weakened forearm pronation

- Weakened finger flexion

Diagnosis of Median Nerve Palsy

History and Physical

- The effect of trauma on the median nerve depends on the site of the injury and may involve the palm, forearm, arm, or axilla. The damage to the nerve can lead to motor, sensory, and vasomotor loss. Most injuries to the median nerve occur at the wrist. Although carpal tunnel syndrome represents the main clinical picture, several injuries can affect the nerve. These lesions are addressable in a distal to proximal manner, from the wrist to the axilla and at the brachial plexus.

Checking the CMC joint

- Hold the metacarpal of the thumb with your hand and push and pull the thumb along its long axis. When the joint is normal, it does not move up and down during the maneuver, but when the joint is subluxated it does.

- Take hold of the thumb by its metacarpal, lift it off and across the palm as much as possible. If the terminal phalanx of the thumb can now face the base of the little or the ring finger, it indicates that there is no contracture of this joint in external rotation.

Checking the MCP joint

- If there is swelling of this joint, or, if on passively moving the joint you feel crepitus or elicit abnormal or excessive movement in any direction, it suggests arthritis of the joint. Radiographic examination is indicated.

- Ask the patient to hold the thumb stiff whilst you push it back at the terminal phalanx. When there is instability, this joint buckles into a hyperextended position (the so-called “Z” deformity) during this maneuver. In many hands, the Z deformity (MCP joint extension) is present to a varying extent even whilst the thumb is at rest {indicating instability of the MCP joint in flexion} and becomes even more pronounced when you do this test.

Special Test

- Tinel test and Phalen test – are of fundamental importance for the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. If the history and physical exam are inconclusive to differentiate between a nerve root injury and a distal median nerve injury, electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction study are diagnostic options.

- A nerve conduction test – can detect impairment in the median nerve conduction across the carpal tunnel while having normal conduction along everywhere else in its path. An EMG can be used to determine if there is pathology within the muscles innervated by the median nerve. Of note, the usefulness in EMG is in the exclusion of polyneuropathy or radiculopathy. Nerve conduction studies have demonstrated to be up to 99% specific for the carpal tunnel, although it may be normal in patients with mild symptoms.[rx][rx]

- Tinel’s sign – may also be used to assess for compression at the carpal tunnel. It is considered positive when a repeated tapping over the carpal tunnel reproduces symptoms in the hand consistent with median nerve pathology.

According to the nerve conduction velocity, carpal tunnel syndrome can classify as

-

Mild carpal tunnel syndrome. Prolonged sensory latencies, a very slight decrease in conduction velocity. No suspected axonal degeneration.

-

Moderate carpal tunnel syndrome. Abnormal sensory conduction velocities and reduced motor conduction velocities. No suspected axonal degeneration.

-

Severe carpal tunnel syndrome. Absence of sensory responses and prolonged motor latencies (reduced motor conduction velocities).

-

Extreme carpal tunnel syndrome. Absence of both sensory and motor responses.

Imaging

- X-rays – X-rays of the affected extremity at the elbow and wrist should be obtained to rule out any osseous deformity that may cause nerve entrapment, as well as cervical spine radiographs that may reveal sources of radiculopathy or first rib involvement. Finally, a chest x-ray should be obtained to rule out compression of the medial chord by an apical lung or Pancoast tumor, particularly in a patient with a positive history for smoking.

- Plain radiographs – May be useful during instances where there is a history of trauma, or there is suspicion of a fracture. It can also help to identify cases of osteoarthritis, bony prominences or osteophytes, and the presence of orthopedic hardware that could compress nerves.

- Ultrasound – of the nerve at the elbow and wrist can be used to measure the size of the radial nerve compared to controls, as well as to identify a thrombosis of the radial artery that can lead to ulnar nerve symptoms originating in Guyon’s canal.[rx]

-

Electrodiagnostic studies – Electromyography and nerve conduction studies help to localize the nerve involved as well as where along the course of the nerve it is affected. Additionally, testing can serve as a baseline for comparison with future studies during the course of treatment. It is important to note that normal electrodiagnostic studies do not rule out disease, and clinical correlation should include the patient’s history and physical examination findings.

-

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) – Can be useful in the identification of ganglion cysts, synovial or muscular hypertrophy, edema, vascular disease, as well as nerve changes. The cross-sectional area and space available for the nerve can also be measured and compared to accepted normal values.

-

Nerve ultrasonography – The use of nerve ultrasonography has increased recently. It can measure the cross-sectional area and the longitudinal diameter of the nerve. It can also identify compressive lesions. Ultrasound may also evaluate the presence of local edema. Additionally, ultrasound may help distinguish between different causes of wrist pain that can include tendonitis or osteoarthritis.

-

Serologic studies – There are no blood tests used to specifically support the diagnosis of nerve compression, but the use of these tests may be necessary for medical conditions that can either promote nerve compression or can mimic their symptoms. Some of the most frequently encountered conditions include diabetes and hypothyroidism. The assessment of a patient’s fasting blood glucose, hemoglobin A1c, or thyroid function tests may be helpful in the general management of the patient. Other conditions that could mimic nerve compression include deficiency of vitamin B12 or folate, vasculitides, and fibromyalgia.

-

Electromyography – is also commonly used in the diagnosis of compression neuropathy with muscle denervation. Compressive neuropathies result in increased distal latency and decreased conduction velocity. Thus in patients with cubital tunnel syndrome, one is likely to identify a slowing of conduction in the ulnar nerve segment crossing the elbow.[rx][rx]

-

Both ultrasonic scanning (USS) – and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have sensitivity and specificity over 80% in diagnosis. MRI and USS are also helpful to identify other causes of compression, which may not be picked up on plain radiograph films such as soft tissue swelling and lesions such as neuroma, ganglions, aneurysms, etc.[rx]

- On musculoskeletal (MSK) ultrasound – a cross-sectional area of 9 mm or more is 87% sensitive for carpal tunnel syndrome.[rx] Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Xray are typically not indicated for suspected carpal tunnel syndrome. MRI is an option for suspected medial nerve entrapment at the wrist. This imaging can be useful in diagnosis when the patient is not recovering from an expected coarse. The MRI can help identify hypertrophy of the synovium and a space-occupying lesion such as a ganglion cyst.

Treatment of Median Nerve Palsy

Conservative treatment options depend on the severity of the injury and the patient’s symptoms. They include

- Bracing or splinting – Your doctor may prescribe a padded brace or splint to wear at night to keep your elbow in a straight position. If initially starting with night splints, and the patient does not have relief after one month, the recommendation is to continue for another one to two months but add another conservative treatment modalities to the care plan. Splints can be worn at night or continuously, but have continuous use has not been shown to be superior to night time wearing the splint.[rx][rx]

- Immobilization – with proper splints for at least 2 to 4 weeks, or until the symptoms have resolved.

- Nerve gliding exercises – Some doctors think that exercises to help through the cubital tunnel at the elbow and the Guyon’s canal at the wrist can improve symptoms. These gliding exercises may also help prevent stiffness in the arm and wrist.

- Exercises – that strengthen the interosseous muscles and lubricants are recommended. The individual should be taught to exercise each finger and thumb in abduction and adduction motion while the hand is pronated. In addition, the MCP and ICP joints should be exercised and over time the interosseous and lumbrical will gain strength.

- An elbow pad – This helps with pressure on the joint.

- Occupational and physical therapy – This will help your arm and hand become stronger and more flexible.

- Nerve-gliding exercise – Do this to help guide the nerve through the proper “tunnels” in the wrist and elbow.

- Bracing or Splinting – Immobilizing your arm in a brace for a few weeks or longer can help you to avoid additional damage. Your doctor may also suggest wearing a splint at night to prevent your arm from bending while you sleep.

- Hand Therapy – Your doctor may recommend hand therapy, which is performed by physical and occupational therapists at NYU Langone. Hand therapy involves strengthening and stretching exercises for your hand as well as your arm and elbow. NYU Langone therapists certified in hand therapy can work with you to develop an exercise plan specific to your needs. Although you may initially visit your therapist several times per week, you can eventually perform the exercises at home

- Manual Therapeutic Technique (MTT) – hands-on care including soft tissue massage, stretching and joint mobilization by a physical therapist to improve alignment, mobility, and range of motion. The use of mobilization techniques also helps to modulate pain.

- Therapeutic Exercises (TE) – including stretching and strengthening exercises to regain range of motion and strengthen muscles of the arm, forearm or wrist area to support, stabilize and decrease the stresses place on the median nerve.

- Neuromuscular Reeducation (NMR) – to restore stability, improve movement techniques and mechanics of the involved arm, forearm or wrist area. It also reduces stress on the joint surfaces in daily activities.

- Modalities – including the use of ultrasound electrical stimulation, ice, cold, laser, and others to decrease pain and inflammation of the involved joint.

Medication

If the injury is severe and pain is intolerable the following medicine can be considered to prescribe

- NSAIDs – Prescription-strength drugs that reduce both pain and inflammation. Pain medicines and anti-inflammatory drugs help to relieve pain and stiffness, allowing for increased mobility and exercise. There are many common over-the-counter medicines called non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). They include and Ketorolac, Aceclofenac, Naproxen, Etoricoxib.

- Corticosteroids – Also known as oral steroids, these medications reduce inflammation. Oral prednisone at the dose of 20 mg for 10 to 14 days shows the improvement of the patient’s pain related to nerve function compared to the placebo up to eight weeks following the medication coarse.[rx][rx]

- Muscle Relaxants – These medications provide relief from associated muscle spasms.

- Neuropathic Agents – Drugs(pregabalin & gabapentin) that address neuropathic—or nerve-related—pain. This includes burning, numbness, and tingling.

- Opioids – Also known as narcotics, these medications are intense pain relievers that should only be used under a doctor’s careful supervision.

- Topical Medications – These prescription-strength creams, gels, ointments, patches, and sprays help relieve pain and inflammation through the skin.

- Calcium & vitamin D3 – to improve bone health and healing fracture. As a general rule, men and women age 50 and older should consume 1,200 milligrams of calcium a day, and 600 international units of vitamin D a day.

- Antidepressants – A drug that blocks pain messages from your brain and boosts the effects of endorphins (your body’s natural painkillers).

- B1, B6, B12 – It helps to erase the chronic radiating pain and work as a neuropathy agent.

- Intra-articular corticosteroid injections – may be useful for symptomatic injury especially where there is a considerable inflammatory component. The delivery of the corticosteroid directly. It may reduce local inflammation associated with injury and minimize the systemic effects of the steroid.

Surgery

Surgery involves excising the tissue or removing parts of the bone compressing the nerve.

- Many tendon transfers – have been shown to restore opposition to the thumb and provide thumb and finger flexion. In order to have optimal results the individual needs to follow the following principles of tendon transfer is normal tissue equilibrium, movable joints, and a scar-free bed. If these requirements are met then certain factors need to be considered such as matching up the lost muscle mass, fiber length, and cross-sectional area and then pick out muscle-tendon units of similar size, strength, and potential excursion.

- For patients with low median nerve palsy – it has been shown that the flexor digitorum superficialis of the long and ring fingers or the wrist extensors best approximate the force and motion that is required to restore full thumb opposition and strength. This type of transfer is the preferred method for median nerve palsy when both strength and motion are required. In situations when only thumb mobility is desired, the extensor indicis proprius is an ideal transfer.

- For high median nerve palsy – the brachioradialis or the extensor carpi radialis longus transfer is more appropriate to restore lost thumb flexion and side-to-side transfer of the flexor digitorum profundus of the index finger are generally sufficient.[rx] To restore independent flexion of the index finger could be performed by using the pronator teres or extensor carpi radialis ulnaris tendon muscle units. All of the mentioned transfers are generally quite successful because they combine a proper direction of action, pulley location, and tendon insertion.[rx]

Complications

Sensory fibers are more prone to damage from nerve compression compared to motor fibers; thus, paresthesias and numbness and tingling are often the first signs of carpal tunnel syndrome. Motor fibers are affected as the severity of carpal tunnel syndrome progresses. Patients often have weakness in thumb abduction and opposition. Fine motor skills become affected; patients have difficulty dressing themselves or opening jars. As sensory fibers die, the pain gradually subsides, while motor fibers die, the muscles atrophy. Patients may also lose their ability to determine two-point differentiation between two objects, 6 mm apart.[rx][rx]

Pillar pain is common with surgery, pain lateral to the site of surgical release.[rx] Surgical decompression failure is often attributable to the development of fibrosis or failure to completely release the flexor retinaculum.[rx] Surgical revision is necessary in these cases.

Complications of surgery for carpal tunnel syndrome can include the following[rx][rx]:

-

Inadequate division of the transverse carpal ligament

-

Injuries of the recurrent motor and palmar cutaneous branches of the median nerve

-

Vascular injuries of the superficial palmar arch

-

Lacerations of the median and ulnar trunk

-

Postoperative wound infections

-

Painful scar formation

-

Complex regional pain syndrome

References