Femur shaft fractures have become safe and reproducible since the advent of the popularization of intramedullary nailing, however, many femoral shaft fractures are complicated by associated fractures, extensive comminution, extensive contamination, and arterial injury compartmental syndrome. Other conditions associated with the use of femoral nailing include femora nonunions, broken hardware, acute fractures with prior implants, and infections. The management of these complex femoral shaft fractures demands special techniques for a successful outcome.

Anatomy

The femur is the long bone of the thigh and the largest and strongest bone in the human anatomy. The proximal femur has large muscle attachments and a joint at the pelvis forming the hip. The distal femur also has large muscle-group attachments and forms the knee joint with the proximal tibia. The sites of fractures are often named in relation to the anatomy where the fracture occurs.

The femur has many common names and medical names which describe different portions of the bone. The femoral shaft is the diaphysis and is commonly fractured in trauma. The head of the femur is the proximal-most portion of the bone which directly joins to the pelvis forming the hip joint. The femoral neck is the region of bone joining the head to the femoral shaft. The greater and lesser trochanter are protuberances of bone on the proximal end of the femur, and each aid in defining the location of fractures. The distal femur has structures involved in the knee joint called condyles and epicondyles for muscle attachment.

Examining the anatomy of the injured limb should include all systems involved, including circulation, peripheral nerves, and motor function. Injuries often affect these non-boney structures due to the force causing the fracture or dislocation of the femur, also injuring surrounding anatomy. Absent or decreases in the circulation or sensation of the lower limb could direct care and should be carefully monitored before and after immobilization.[1][2]

Types of Femur Shaft Fractures

There are many classifications for femoral neck fracture including the most common clinical classifications by Garden and Pauwel which includes the following[rx][rx]

The Garden classification

-

Type I: Incomplete fracture – valgus impacted-non displaced

-

Type II: Complete fracture – nondisplaced

-

Type III: Complete fracture – partial displaced

-

Type IV: Complete fracture – fully displaced

The Garden classification is the most used system used to communicate the type of fracture. For treatment, it is often simplified into non-displaced (Type 1 and Type 2) versus displaced (Type 3 and Type 4)

Winquist and Hansen Classification

| Type 0 | • No comminution | |

| Type I | • An insignificant amount of comminution | |

| Type II | • Greater than 50% cortical contact | |

| Type III | • Less than 50% cortical contact | |

| Type IV | • Segmental fracture with no contact between proximal and distal fragment |

OTA Classification

| 32A – Simple | • A1 – Spiral • A2 – Oblique, angle > 30 degrees • A3 – Transverse, angle < 30 degrees |

|

| 32B – Wedge | • B1 – Spiral wedge • B2 – Bending wedge • B3 – Fragmented wedge |

|

| 32C – Complex | • C1 – Spiral • C2 – Segmental • C3 – Irregular |

Pauwel classification

The Pauwel classification also includes the inclination angle of the fracture line relative to the horizontal. Higher angle and more vertical fractures exhibit greater instability due to higher shear force. These fractures also have a higher risk of osteonecrosis postoperatively.

-

Type I <30 degrees

-

Type II 30-50 degrees

-

Type III >50 degrees

Types of Femur Shaft Fractures

Femur fractures vary greatly, depending on the force that causes the break. The pieces of bone may line up correctly (stable fracture) or be out of alignment (displaced fracture). The skin around the fracture may be intact (closed fracture) or the bone may puncture the skin (open fracture).

Doctors describe fractures to each other using classification systems. Femur fractures are classified depending on:

- The location of the fracture (the femoral shaft is divided into thirds: distal, middle, proximal)

- The pattern of the fracture (for example, the bone can break in different directions, such as crosswise, lengthwise, or in the middle)

- Whether the skin and muscle over the bone is torn by the injury

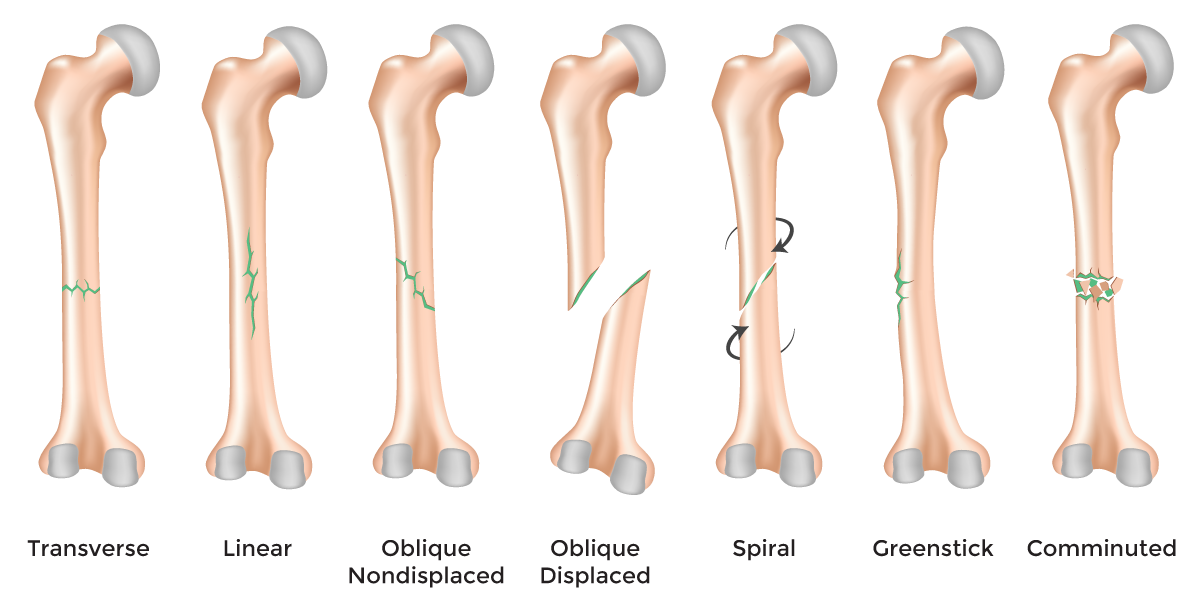

The most common types of femoral shaft fractures include:

- Transverse fracture – In this type of fracture, the break is a straight horizontal line going across the femoral shaft.

- Oblique fracture – This type of fracture has an angled line across the shaft.

- Spiral fracture – The fracture line encircles the shaft like the stripes on a candy cane. A twisting force to the thigh causes this type of fracture.

- Comminuted fracture – In this type of fracture, the bone has broken into three or more pieces. In most cases, the number of bone fragments corresponds with the amount of force needed to break the bone.

- Open fracture – If a bone breaks in such a way that bone fragments stick out through the skin or a wound penetrates down to the broken bone, the fracture is called an open or compound fracture. Open fractures often involve much more damage to the surrounding muscles, tendons, and ligaments. They have a higher risk for complications—especially infections—and take a longer time to heal.

Causes of Femur Shaft Fractures

- Sudden forceful fall down

- Road traffic accident

- Falls – Falling onto an outstretched hand is one of the most common causes of the broken shaft of the femur.

- Sports injuries – Many necks of femur fracture occur during contact sports or sports in which you might fall onto an outstretched hand — such as in-line skating or snowboarding.

- Motor vehicle crashes – Motor vehicle crashes can cause necks of femur fracture to break, sometimes into many pieces, and often require surgical repair.

- Have osteoporosis – a disease that weakens your bones

- Eave low muscle mass or poor muscle strength – or lack agility and have poor balance (these conditions make you more likely to fall)

- Walk or do other activities in snow or on the ice – or do activities that require a lot of forwarding momenta, such as in-line skating and skiing

- Wave an inadequate intake of calcium or vitamin D

- Football or soccer, especially on artificial turf

- Rugby

- Horseback riding

- Hockey

- Skiing

- Snowboarding

- In-line skating

- Jumping on a trampoline

Symptoms of Femur Shaft Fractures

Common symptoms of fractures include

- Severe pain that might worsen when gripping or squeezing or moving your hip.

- Inability to move immediately after a fall

- Severe pain in your thigh or groin.

- Inability to put weight on your leg on the side of your injured thighs.

- Stiffness, bruising and swelling in and around your hip area

- Shorter leg on the side of your injured thighs.

- Turning outward of your leg on the side of your injured

- Swelling

- Tenderness

- Bruising

- Obvious deformity, such as a bent hip.

- Pain

- Pain, especially when flexing the hip

- Deformity of the wrist, causing it to look crooked and bent.

- Your hip is in great pain.

Diagnosis of Femur Shaft Fractures

History

Your doctor in the emergency department may ask the following questions

-

How – How was the fracture created, and, if chronic, why is it still open? (underlying etiology)

-

When – How long has this fracture been present? (e.g., chronic less than 1 month or acute, more than 6 months)

- Where – Where on the body parts is it located? Is it in an area that is difficult to offload, complicated, or keep clean? Is it in an area of high skin tension? Is it near any vital organ and structures such as a major artery?

- What is your Past – Has your previous medical history of fracture? Are you suffering from any chronic disease, such as hypertension, blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, previous major surgery? What kind of medicine did you take? What is your food habits, geographic location, Alcohol, tea, coffee consumption habit, anabolic steroid uses for athletes, etc?

Physical

Physical examination is done by your doctor, consisting of palpation of the fracture site, eliciting boney tenderness, edema, swelling. If the fracture is in the dept of a joint, the joint motion, normal movement will aggravate the pain.

- Inspection – Your doctor also check superficial tissue, skin color, involving or not only the epidermal layer or Partial-thickness affects the epidermis and extend into the dermis, but full-thickness also extends through the dermis and into the adipose tissues or full-thickness extends through the dermis, and adipose exposes muscle, bone, evaluate and measure the depth, length, and width of the fracture. Access surrounding skin tissue, fracture margins for tunneling, rolled, undermining fibrotic changes, and if unattached and evaluate for signs and symptoms of infect warm, pain, delayed healing.

- Palpation – Physical examination may reveal tenderness to palpation, swelling, edema, tenderness, worm, temperature, open fracture, closed fracture, microtrauma, and ecchymosis at the site of fracture. Condition of the surrounding skin and soft tissue, quality of vascular perfusion and pulses, and the integrity of nerve function.

- Motor function – Your doctor may ask the patient to move the injured area to assist in assessing muscle, ligament, and tendon function. The ability to move the joint means only that the muscles and tendons work properly, and does not guarantee bone integrity or stability. The concept that “it can’t be fractured because you can move it” is not correct. The jerk test and manual test are also performed to investigate the motor function.

- Sensory examination – assesses sensations such as light touch, worm, paresthesia, itching, numbness, and pinprick sensations, in its fracture side. Sensory 2-point discrimination

- Range of motion – A range of motion examination of the fracture associate joint and it’s surrounding joint may be helpful in assessing the muscle, tendon, ligament, cartilage stability. Active assisted, actively resisted exercises are performed around the injured area joint.

- Blood pressure and pulse check – Blood pressure is the term used to describe the strength of blood with which your blood pushes on the sides of your arteries as it’s pumped around your body. An examination of the circulatory system, feeling for pulses, blood pressure, and assessing how quickly blood returns to the tip of a toe to heart and it is pressed the toe turns white (capillary refill).

Lab Test

Laboratory tests should be done as an adjunct in overall medical status for surgical treatment.

- CBC, ESR test

- Random blood sugar, glucose, and routine diabetes test if the patient has diabetes mellitus.

- Microscopic urine examination test, and stool test.

- ECG, EKG test for heart abnormality is present

- Ultrasonography test in some cases.

- Normalized hemoglobin, hematocrit test

- Coagulation profile with bleeding time and coagulation time test, prothrombin time (PT) test for surgery if needed,

- Partial thromboplastin time (PTT), and platelet counts will be needed for operative intervention.

- Serum creatinine test,

- Serum lipid profile

- Serum uric acid test

Radiography

- Radiographs-AP pelvis, AP and lateral hip, AP and lateral femur, AP and lateral knee.

- Anterior-posterior (AP) and lateral radiographs are typically obtained.[rx] In order to rule out other injuries, hip, pelvis, and knee radiographs are also obtained.[rx] The hip radiograph is of particular importance because femoral shaft fractures can lead to osteonecrosis.[rx]

Plain radiograph

- Shenton’s line disruption – loss of contour between a normally continuous line from the medial edge of the femoral and inferior edge of the superior pubic ramus

- Femur often positioned in flexion and external rotation (due to unopposed iliopsoas)

- Asymmetry of lateral femoral neck/head

- Sclerosis in fracture plane

- Smudgy sclerosis from impaction

- Bone trabeculae angulated

- Nondisplaced fractures may be subtle on x-ray

Computed Tomography

- CT may be useful and can give significant information in comparison with that obtained with conventional radiography in the evaluation of complex or occult fractures,[rx] assessments of fracture healing as well as post-surgical evaluation.[rx]

- CT may be indicated for the confirmation of occult fractures suspected on the basis of physical examination when plain films are normal.

- Help better characterize the fracture pattern or delineate a subtle fracture line, often included in part of a trauma assessment and can be extended to include the femoral neck.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- Although this modality is not the first choice in evaluating acute femoral neck fracture, it is a powerful diagnostic tool to assess bony, ligamentous and soft tissue abnormalities associated with these fractures.

- MRI has proved to be a very important diagnostic tool for delineating perforation of triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC),[rx] perforation of interosseous ligaments.

Medical assessment should include basic labs (CBC, BMP, and PT/INR if applicable) as well as a chest radiograph and EKG. Elderly patients with known or suspected cardiac disease may benefit from preoperatively cardiology evaluation. Preoperative medical optimization is vital in the geriatric population.

Differential Diagnosis

-

Hip dislocation – Displacement of the femoral head from the acetabulum

-

Intertrochanteric fracture – the fracture line is more distal and lies between the greater and lesser trochanter

-

Subtrochanteric fracture – the fracture Line is within 5 cm distal to the lesser trochanter

-

Femur fracture – the fracture line is within the femoral diaphysis

-

Osteoarthritis – pain that is more chronic. Usually, patients complain of groin pain. Pain that worsens with activity or stairs

Treatment of Femur Shaft Fractures

Emergency Management

Pain control

- Intravenous opiates are often used as patients typically in severe pain

- Femoral nerve block (link)

- Highly effective for management of pain in femoral neck fractures

- Lower side effect profile than systemic analgesia

- Always calculate your toxic dose of local anesthetic to avoid local anesthetic systemic toxicity

- Closed fractures should be placed in long leg splint and can also be placed in traction

- Open Fractures should receive antibiotics and should proceed to OR for irrigation/debridement

- Skin Traction (Hare or Thomas)

Tractions

Surface Traction Splints

Commonly used tractions are Thomas, Hare, Sager, Kendrick, CT-6, Donway, and Slishman traction splints. We will discuss the most common Traction splints: Hare, Sage. It maintained bipolar traction with 2 steel rods on both sides of the limb. Most importantly, the Hare traction splint was more compact, easy, and effective for a femur fracture. The Hare splint is not effective with proximal femur shaft fracture because the ischial pad may rest directly under the fracture. An adult unit cannot be adjusted for pediatric patients. Below is a simplified application guide.

-

Stabilize the injured leg.

-

Position splint against the uninjured leg to adjust the length.

-

Place splint under the patient’s leg and place the ischial pad against the ischial tuberosity.

-

Adjust splint to length then attach ischial strap over the groin and thigh.

-

Apply the ankle hitch to the patient.

-

Apply gentle but firm traction until the injured leg length is approximately equal to the uninjured leg length.

-

Secure the remaining velcro straps around the leg.

-

Reassess neurovascular function.

Sager Traction Splints

Sager traction is unipolar traction. One steel rod sits between a patient’s legs and applies traction from the ankle with counter pressure directed onto the ischial tuberosity. Sager splint sits between the leg against the ischial tuberosity, so it is more effective for proximal femur fracture than hare splint. Also, one Sager splint can be used for a bilateral femur fracture. However, there is increased the risk of damage to the genitalia as the splint can move from the initial ischial tuberosity placement during transport. Sager traction splint can measure the actual traction applied on the gauge. The optimal traction is roughly 10% to 15% of a patient’s body weight.

-

Position the splint between the patient’s legs, resting the saddle against the ischial tuberosity.

-

Attach the strap to the thigh.

-

Secure the ankle strap tight.

-

Gently extend the inner shaft until the desired amount of traction, approximately 10% of the patient’s body weight.

-

Adjust the thigh/leg/foot strap.

-

Reassess neurovascular function.

Treatment available can be broadly

- Skeletal traction – Available evidence suggests that treatment depends on the part of the femur that is fractured. Traction may be useful for femoral shaft fractures because it counteracts the force of the muscle pulling the two separated parts together, and thus may decrease bleeding and pain.[rx] Traction should not be used in femoral neck fractures or when there is any other trauma to the leg or pelvis.[rx][rx] It is typically only a temporary measure used before surgery. It only considered definitive treatment for patients with significant comorbidities that contraindicate surgical management.[rx]

- Get medical help immediately – If you fall on an outstretched arm, get into a car accident or are hit while playing a sport and feel intense pain in your hip area, then get medical care immediately. Femoral shaft fractures cause significant pain in the front part of your hip, closer to the base of your back. You’ll innately know that something is seriously wrong because you won’t be able to lift your leg up. Other symptoms include immediate swelling and/or bruising near the fracture, grinding sounds with arm movements and potential numbness and tingling in the leg.

- Apply ice – After you get home from the hospital necks of femur fractures (regardless if you had surgery or not), you should apply a bag of crushed ice (or something cold) to your injured in order to reduce the swelling and numb the pain. Ice therapy is effective for acute (recent) injuries that involve swelling because it reduces blood flow by constricting local blood vessels. Apply the crushed ice to your injured area for 15 minutes three to five times daily until the soreness and inflammation eventually fades away

Lightly exercise after the pain fades – After a couple of weeks when the swelling has subsided and the pain has faded away, remove your arm sling for short periods and carefully move your hip joints in all different directions. Don’t aggravate the necks of the femur so that it hurts, but gently reintroduce movements to the involved joints and muscles. Start cautiously, maybe starting with light and then progress to holding light weights (five-pound weights to start). Your necks of femoral shaft fractures need to move a little bit during the later phases of the injury to stimulate complete recovery.

- Practice stretching and strengthening exercises – of the fingers, leg if your doctor recommends them.

- A splint – which you might use for a few days to a week while the swelling goes down; if a splint is used initially, a cast is usually put on about a week later.

- A cast – which you might need for six to eight weeks or longer, depending on how bad the break is (you might need a second cast if the first one gets too loose after the swelling goes away.)

- Get a supportive arm sling – Due to their anatomical position, necks of femoral shaft fractures can’t be cast like a broken limb can. Instead, a supportive arm sling or “figure-eight” splint is typically used for support and comfort, either immediately after the injury if it’s just a hairline fracture or following surgery, if it’s a complicated fracture. A figure-eight splint wraps around both hip and the base of your back in order to support the injured hip and keep it positioned up and back. Sometimes a larger swath of material is wrapped around the sling to keep it closer to your body. You’ll need to wear the sling constantly until there is no pain with arm movements, which takes between two to four weeks for children or four to eight weeks for adults.

- Get a referral to physical therapy – Once you’ve recovered and able to remove your arm sling splint for good, you’ll likely notice that the muscles surrounding your hip and knee look smaller and feel weaker. That’s because muscle tissue atrophies without movement. If this occurs, then you’ll need to get a referral for some physical rehabilitation. Rehab can start once you are cleared by your orthopedist, are pain-free, and can perform all the basic arm and necks of femur fracture movements. A physiotherapist or athletic trainer can show you specific rehabilitation exercises and stretches to restore your muscle strength, joint movements, and flexibility

- Rigid fixation – osteosynthesis with locking plate, hook plate fixation, fixation with a locking plate, screws, Knowles pin fixation.

- A splint – which you might use for a few days to a week while the swelling goes down; if a splint is used initially, a cast is usually put on about 7 a week later.

- A cast – which you might need for six to eight weeks or longer, depending on how bad the break is (you might need a second cast if the first one gets too loose after the swelling goes away.)

Rest your leg

- Depending on what you do for a living and if the injury is to your dominant side, you may need to take a couple of weeks off work to recuperate.

- Healing takes between four to six weeks in younger people and up to 12 weeks in the elderly, but it depends on the severity.

- Athletes in good health are typically able to resume their sporting activities within two months of breaking they’re ulnar styloid depending on the severity of the break and the specific sport.

- Sleeping on your back (with the sling on) is necessary to keep the pressure off your shoulder and prevent stressing the femur injury.

Physical therapy

- Although there will be some pain, it is important to maintain arm motion to prevent stiffness. Often, patients will begin doing exercises for elbow motion immediately after the injury. After a fracture, it is common to lose some leg strength. Once the bone begins to heal, your pain will decrease and your doctor may start gentle hip, knee exercises. These exercises will help prevent stiffness and weakness. More strenuous exercises will be started gradually once the fracture is completely healed.

Follow-up care

- You will need to see your doctor regularly until your fracture heals. During these visits, he or will take x-rays to make sure the bone is healing in a good position. After the bone has healed, you will be able to gradually return to your normal activities.

Breathing Exercise

- To elevate lung/ breathing problem or remove the lung congestion if needed.

Do no HARM for 72 hours after injury

- Heat – Heat applied to fracture and injured side by hot baths, electric heat, saunas, heat packs, etc has the opposite effect on the blood flow. Heat may cause more fluid accumulation in the fracture joints by encouraging blood flow. Heat should be avoided when inflammation is developing in the acute stage. However, after about 72 hours, no further inflammation is likely to develop and heat can be soothing.

- Alcohol – stimulates the central nervous system that can increase bleeding and swelling and decrease healing.

- Running and movement – Running and walking may cause further damage, and causes healing delay.

- Massage – A massage also may increase bleeding and swelling. However, after 72 hours of your fracture, you can take a simple message, and applying heat may be soothing the pain.

Medication

The following medications may be considered by your doctor to relieve acute and immediate pain, long term treatment

- Antibiotic – Cefuroxime or Azithromycin, or Flucloxacillin or any other cephalosporin/quinolone, meropenem antibiotic must be used to prevent infection or clotted blood removal to prevent further swelling, inflammation, and edema.

- NSAIDs – Prescription-strength drugs that reduce both pain and inflammation. Pain medicines and anti-inflammatory drugs help to relieve pain and stiffness, allowing for increased mobility and exercise. There are many common over-the-counter medicines called non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). They include first choice NSAIDs is Ketorolac, then Etoricoxib, then Aceclofenac, naproxen. As you are taking pain medication or NSAIDs, your doctor must prescribe a standard anti-ulcer drug, such as omeprazole, pantoprazole, esomeprazole, dexlansoprazole, etc.

- Muscle Relaxants – These medications provide relief from spinal muscle spasms, spasticity. Muscle relaxants, such as baclofen, tolperisone, eperisone, methocarbamol, carisoprodol, and cyclobenzaprine, may be prescribed to control postoperative muscle spasms, spasticity, stiffness, contracture.

- Calcium & vitamin D3 – To improve bone health, blood clotting, helping muscles to contract, regulating heart rhythms, nerve functions, and healing fractures. As a general rule, too absorbed more minerals for men and women age 50 and older should consume 1,200 milligrams of calcium a day, and 600 international units of vitamin D a day to heal back pain, fractures, osteoarthritis.

- Neuropathic Agents – Drugs(pregabalin & gabapentin) that address neuropathic—or nerve-related—pain. This includes burning, numbness, tingling sensation, and paresthesia.

- Glucosamine & Diacerein, Chondroitin sulfate – can be used to tighten the loose tendon, cartilage, ligament, and cartilage, ligament regenerates cartilage or inhabits the further degeneration of cartilage, ligament. The dosage of glucosamine is 15oo mg per day in divided dosage and chondroitin sulfate approximately 500mg per day in different dosages, and diacerein minimum of 50 mg per day may be taken if the patient suffers from osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and any degenerative joint disease.[rx]

- Topical Medications and essential oil – These prescription-strength creams, gels, ointments, patches, and sprays help relieve pain and inflammation in acute trauma, pain, swelling, tenderness through the skin. If the fracture is closed and not open fracture then you can use this item.

- Antidepressants – A drug that blocks pain messages from your brain and boosts the effects of endorphins in your body’s natural painkillers. It also helps in neuropathic pain, anxiety, tension, and proper sleep.

- Corticosteroids – Also known as oral steroids, these medications reduce inflammation. To heal the nerve inflammation and clotted blood in the joints.

- Dietary supplement – To eradicate the healing process from fracture your body needs a huge amount of vitamin C, and vitamin E. From your dietary supplement, you can get it, and also need to remove general weaknesses & improved health.

- Cough Syrup – If your doctor finds any chest congestion or fracture-related injury in your chest, dyspnoea, post-surgical breathing problem, then advice you to take bronchodilator cough syrup.

What To Eat and What to avoid

Eat Nutritiously During Your Recovery

All bones and tissues in the body need certain micronutrients in order to heal properly and in a timely manner. Eating a nutritious and balanced diet that includes lots of minerals and vitamins is proven to help heal broken bones and all types of fractures. Therefore, focus on eating lots of fresh food produce (fruits and veggies), whole grains, cereal, beans, lean meats, seafood, and fish to give your body the building blocks needed to properly repair your fracture. In addition, drink plenty of purified mineral water, milk, and other dairy-based beverages to augment what you eat.

- Broken bones or fractures bones need ample minerals (calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, boron, selenium, omega-3) and protein to become strong and healthy again.

- Excellent sources of minerals/protein include dairy products, tofu, beans, broccoli, nuts and seeds, sardines, sea fish, and salmon.

- Important vitamins that are needed for bone healing include vitamin C (needed to make collagen that your body essential element), vitamin D (crucial for mineral absorption, or machine for mineral absorber from your food), and vitamin K (binds calcium to bones and triggers more quickly collagen formation).

- Conversely, don’t consume food or drink that is known to impair bone/tissue healing, such as alcoholic beverages, sodas, fried fast food, most fast food items, and foods made with lots of refined sugars and preservatives.

Surgery

Type 1 Fractures (Transepiphyseal)

Closed reduction and spica cast immobilization

- Considered for nondisplaced or minimally displaced fractures up to age 4 years

Internal fixation

- Appropriate for older children or with displaced fractures

- Closed reduction or open reduction is performed to achieve anatomic alignment

- Smooth pin fixation may be acceptable for small, young children when supplemented with a spica cast

- Cannulated screw fixation is appropriate for older children and adolescents

Type 2 Fractures (Transcervical) and Type 3 Fractures (Cervicotrochanteric)

Closed reduction and spica cast immobilization

- Considered only for nondisplaced or minimally displaced fractures up to age 4 years

Internal fixation

- Appropriate for older children or with displaced fractures

- Closed reduction or open reduction is performed to achieve adequate alignment

- Smooth pin fixation may be acceptable for small, young children when supplemented with a spica cast

- Cannulated screw fixation is appropriate for older children and adolescents

- Crossing the physis may be necessary to achieve adequate fixation

- If the fixation stops short of the physis, spica cast immobilization should be considered

Type 4 Fractures

Closed reduction and spica cast immobilization

- Nondisplaced or minimally displaced fractures up to age 3-4 years

- Cross-sectional imaging may be necessary to confirm that reduction is adequate and maintained within the cast

Closed reduction, pin fixation, and spica cast immobilization

- May be considered for children up to age 6 years

Rigid internal fixation

- Consider for displaced fractures in children greater than age 3 years

- Closed reduction or open reduction via an anterolateral approach

- Proximal femoral plate or compression hip screw

Post-operative immobilization is based on fracture type, patient age, and treatment. A period of 8-10 weeks in a spica cast is recommended for those children who cannot be compliant with a non-weight bearing or partial weight-bearing. The older adolescent with rigid fixation can begin partial

weight-bearing within 2 weeks.

- Internal repair using screws. Metal screws are inserted into the bone to hold it together while the fracture heals. Sometimes screws are attached to a metal plate that runs down the femur.

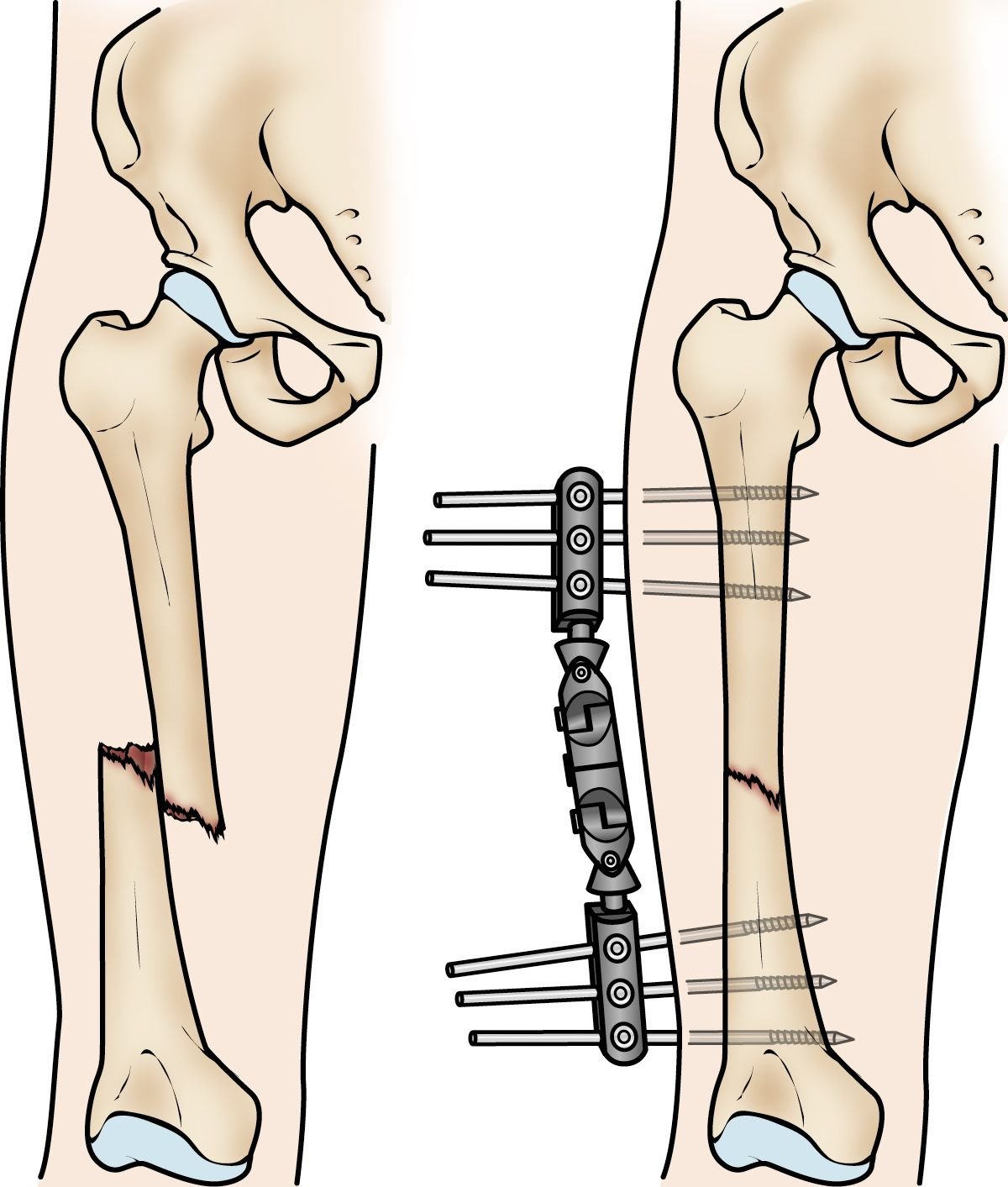

External fixators

- External fixators can be used to prevent further damage to the leg until the patient is stable enough for surgery.[rx] It is most commonly used as a temporary measure. However, for some select cases, it may be used as an alternative to intramedullary nailing for definitive treatment.[rx][rx]

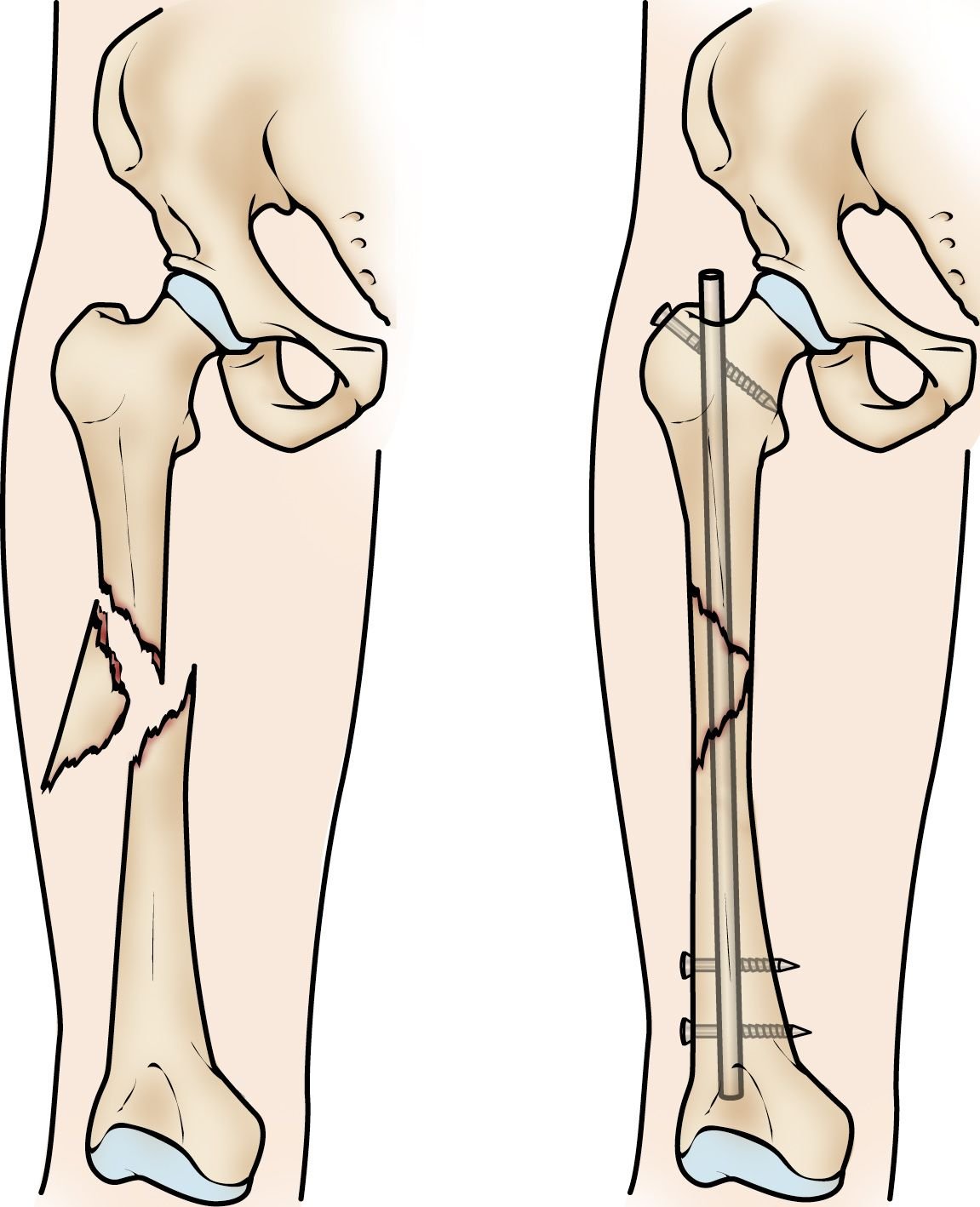

Intramedullary Nailing

- For femoral shaft fractures, reduction and intramedullary nailing are currently recommended.[rx] The bone is re-aligned, then a metal rod is placed into the femoral bone marrow, and secured with nails at either end. This method offers less exposure, a 98%-99% union rate, lower infection rates (1%-2%) and less muscular scarring.[rx][rx][rx]

The timing of surgery

- Most femur fractures are fixed within 24 to 48 hours. On occasion, fixation will be delayed until other life-threatening injuries or unstable medical conditions are stabilized. To reduce the risk of infection, open fractures are treated with antibiotics as soon as you arrive at the hospital. The open wound, tissues, and bone will be cleaned during surgery. For the time between initial emergency care and your surgery, your doctor may place your leg either in a long-leg splint or in traction. This is to keep your broken bones as aligned as possible and to maintain the length of your leg. Skeletal traction is a pulley system of weights and counterweights that holds the broken pieces of bone together. It keeps your leg straight and often helps to relieve pain.

External fixation

- In this type of operation, metal pins or screws are placed into the bone above and below the fracture site. The pins and screws are attached to a bar outside the skin. This device is a stabilizing frame that holds the bones in the proper position. External fixation is usually a temporary treatment for femur fractures. Because they are easily applied, external fixators are often put on when a patient has multiple injuries and is not yet ready for a longer surgery to fix the fracture. An external fixator provides good, temporary stability until the patient is healthy enough for the final surgery. In some cases, an external fixator is left on until the femur is fully healed, but this is not common.

Intramedullary Nailing

- Currently, the method most surgeons use for treating femoral shaft fractures is intramedullary nailing. During this procedure, a specially designed metal rod is inserted into the canal of the femur. The rod passes across the fracture to keep it in position.

An intramedullary nail can be inserted into the canal either at the hip or the knee. Screws are placed above and below the fracture to hold the leg in correct alignment while the bone heals.

Intramedullary nails are usually made of titanium. They come in various lengths and diameters to fit most femur bones.

Plates and screws

- During this operation, the bone fragments are first repositioned (reduced) into their normal alignment. They are held together with screws and metal plates attached to the outer surface of the bone. Plates and screws are often used when intramedullary nailing may not be possible, such as for fractures that extend into either the hip or knee joints.

Rehabilitation

After surgery, the patient should be offered physiotherapy and try to walk as soon as possible, and then every day after that to maximize their chances of a good recovery.[rx]

Complications

- Avascular necrosis

- Premature physical closure

- Delayed union/Non-union

- Blood clots in your legs or lungs

- Bedsores

- Urinary tract infection

- Pneumonia

- Further loss of muscle mass, increasing your risk of falls and injury

- Infection—2% to 17%

- Decubitus ulcers—20%

- Nonunion at IT—1% to 2%

- Nonunion at femoral neck—10% to 30%

- Fracture—3% to 4% (for hemiarthroplasty)

- Dislocation—1% to 10% (for hemiarthroplasty)

- Heterotopic ossification—25% to 40% (for hemiarthroplasty)

- Deep venous thrombosis—50% to 60%

- Pulmonary embolism—7%

- Mechanical failure—IT fractures, 12%

- Osteonecrosis—1% to 17%; early reduction decreases the rate

- Degenerative joint disease—33% to 50%

- Sciatic nerve injury—8% to 19%; approximately 50% of patients recover spontaneously

- Femoral head fracture—7% to 68%

References