Mastodon is a free, open-source federated social network spanning over 800,000 users spread across more than 2,000 servers.

Mastodon v1.6 is here, and it is the first Mastodon release which fully implements the ActivityPub protocol. ActivityPub is a new federated messaging protocol developed by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) which aims to fix the shortcomings of past standards like OStatus.

Mastodon is one of the first platforms, and certainly the first major platform to implement this new standard and prove it in the wild. It was a natural upgrade for our project, as we long ago reached the limits of what OStatus was capable of. And what we needed was better privacy, better defaults, better cryptographic verifiability, and better distribution mechanisms.

This protocol is also very flexible in what it allows you to express and it is naturally extensible as it is based on JSON-LD. Besides allowing Mastodon to fully and reliably exchange the data it currently needs to exchange, it also has a lot of potential for future developments in the area of distributed identities and end-to-end encryption.

Servers which support this new protocol will use it in version 1.6. OStatus is still available as a full-fledged fallback.

Here are some of the juicier highlights from this release:

1. We’ve improved the integrity of distributed conversations. Up until now, the only server which had a full view of a conversation was the server of the conversation’s starter, as all responders sent their replies to it. But the servers of the responders or followers had only an incidental view of the conversation conversation; to get a full view, one would have to either follow the other responders, or get a reply from the conversation starter. Now, the server that receives the replies forwards them to followers’ servers as long as they are public. This means that when opening the conversation view on a different server, it will be as complete as on the origin server. This is especially helpful to those who run single-user instances, as they are the least likely to have already been following all responders.

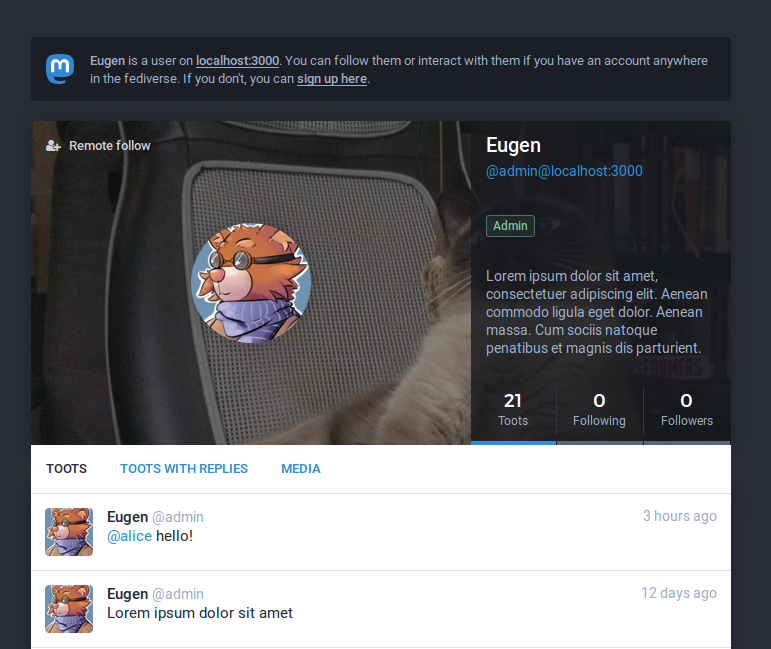

2. Another feature, which is small, but has a big UX effect, is that we can finally fetch account statistics from remote profiles (total toots, number of followers, etc.), as there is now a standardized way of expressing this using ActivityPub. Technically this is not a big deal, but it did confuse new users when they saw someone from another server with a seemingly empty profile, when in reality it had thousands of toots and followers.

3. Speaking of profiles, this release brings you redesigned public profile pages, as well as the ability to pin certain toots on them to be permanently displayed. By default, stand-alone toots are displayed, and there are now tabs for toots with replies and toots with media.

4. The function of getting embed codes for toots is now more accessible — through a button in the web UI, and not just through the OEmbed API. The look of the embedded view has also been refurbished, and an optional script has been added to ensure the embeds have the correct height. I am excited to see Mastodon content appear on other websites.

5. To improve the experience of brand new users, we’ve added something in the old tradition of MySpace Tom — except instead of following some central Tom, new accounts will start off following their local admins (this can be adjusted by the administrator). That way, on your first login you are greeted with a populated home timeline instead of an empty one.

All in all, this release is all about filling the gaps in the server-to-server layer, improving content discovery and first time experience of new users, and making it easier to share Mastodon content.

Today we’ll be looking at how to connect the protocols powering Mastodon in the simplest way possible to enter the federated network. We will use static files, standard command-line tools, and some simple Ruby scripting, although the functionality should be easily adaptable to other programming languages.

First, what’s the end goal of this exercise? We want to send a Mastodon user a message from our own, non-Mastodon server.

So what are the ingredients required? The message itself will be formatted with ActivityPub, and it must be attributed to an ActivityPub actor. The actor must be discoverable via Webfinger, and the delivery itself must be cryptographically signed by the actor.

The actor

The actor is a publicly accessible JSON-LD document answering the question “who”. JSON-LD itself is a quite complicated beast, but luckily for our purposes we can treat it as simple JSON with a @context attribute. Here is what an actor document could look like:

{

"@context": [

"https://www.w3.org/ns/activitystreams",

"https://w3id.org/security/v1"

],

"id": "https://my-example.com/actor",

"type": "Person",

"preferredUsername": "alice",

"inbox": "https://my-example.com/inbox",

"publicKey": {

"id": "https://my-example.com/actor#main-key",

"owner": "https://my-example.com/actor",

"publicKeyPem": "-----BEGIN PUBLIC KEY-----...-----END PUBLIC KEY-----"

}

}

The id must be the URL of the document (it’s a self-reference), and all URLs should be using HTTPS. You need to include an inbox even if you don’t plan on receiving messages in response, because for legacy purposes Mastodon doesn’t acknowledge inbox-less actors as compatible.

The most complicated part of this document is the publicKey as it involves cryptography. The id will in this case refer to the actor itself, with a fragment (the part after #) to identify it–this is because we are not going to host the key in a separate document (although we could). The owner must be the actor’s id. Now to the hard part: You’ll need to generate an RSA keypair.

You can do this using OpenSSL:

openssl genrsa -out private.pem 2048

openssl rsa -in private.pem -outform PEM -pubout -out public.pem

The contents of the public.pem file is what you would put into the publicKeyPem property. However, JSON does not support verbatim line-breaks in strings, so you would first need to replace line-breaks with \n instead.

Webfinger

What is Webfinger? It is what allows us to ask a website, “Do you have a user with this username?” and receive resource links in response. Implementing this in our case is really simple, since we’re not messing with any databases and can hardcode what we want.

The Webfinger endpoint is always under /.well-known/webfinger, and it receives queries such as /.well-known/webfinger?resource=acct:bob@my-example.com. Well, in our case we can cheat, and just make it a static file:

{

"subject": "acct:alice@my-example.com",

"links": [

{

"rel": "self",

"type": "application/activity+json",

"href": "https://my-example.com/actor"

}

]

}

The subject property here consists of the username (same as preferredUsername earlier) and the domain you’re hosting on. This is how your actor will be stored on other Mastodon servers and how people will be able to mention it in toots. Only one link is required in the Webfinger response, and it’s the link to the actor document.

After this is uploaded to your webhost and available under your domain with a valid SSL certificate, you could already look up your actor from another Mastodon by entering alice@my-example.com into the search bar. Although it’ll look quite barren.

The message

ActivityPub messages practically consist of two parts, the message itself (the object) and a wrapper that communicates what’s happening with the message (the activity). In our case, it’s going to be a Create activity. Let’s say “Hello world” in response to my toot about writing this blog post:

Here is how the document could look:

{

"@context": "https://www.w3.org/ns/activitystreams",

"id": "https://my-example.com/create-hello-world",

"type": "Create",

"actor": "https://my-example.com/actor",

"object": {

"id": "https://my-example.com/hello-world",

"type": "Note",

"published": "2018-06-23T17:17:11Z",

"attributedTo": "https://my-example.com/actor",

"inReplyTo": "https://mastodon.social/@Gargron/100254678717223630",

"content": "<p>Hello world</p>",

"to": "https://www.w3.org/ns/activitystreams#Public"

}

}

With the inReplyTo property we’re chaining our message to a parent. The content property may contain HTML, although of course it will be sanitized by the receiving servers according to their needs — different implementations may find use for a different set of markup. Mastodon will only keep p, br, a and span tags. With the to property we are defining who should be able to view our message, in this case it’s a special value to mean “everyone”.

For our purposes, we don’t actually need to host this document publicly, although ideally both the activity and the object would be separately available under their respective id. Let’s just save it under create-hello-world.json because we’ll need it later.

So the next question is, how do we send this document over, where do we send it, and how will Mastodon be able to trust it?

HTTP signatures

To deliver our message, we will use POST it to the inbox of the person we are replying to (in this case, me). That inbox is https://mastodon.social/inbox. But a simple POST will not do, for how would anyone know it comes from the real @alice@my-example.com and not literally anyone else? For that purpose, we need a HTTP signature. It’s a HTTP header signed by the RSA keypair that we generated earlier, and that’s associated with our actor.

HTTP signatures is one of those things that are much easier to do with actual code instead of manually. The signature looks like this:

Signature: keyId="https://my-example.com/actor#main-key",headers="(request-target) host date",signature="..."

The keyId refers to public key of our actor, the header lists the headers that are used for building the signature, and then finally, the signature string itself. The order of the headers must be the same in plain-text and within the to-be-signed string, and header names are always lowercase. The (request-target) is a special, fake header that pins down the HTTP method and the path of the destination.

The to-be-signed string would look something like this:

(request-target): post /inbox

host: mastodon.social

date: Sun, 06 Nov 1994 08:49:37 GMT

Mind that there is only a ±30 seconds time window when that signature would be considered valid, which is a big reason why it’s quite difficult to do manually. Anyway, assuming we’ve got the valid date in there, we now need to build a signed string out of it. Let’s put it all together:

require 'http'

require 'openssl'

document = File.read('create-hello-world.json')

date = Time.now.utc.httpdate

keypair = OpenSSL::PKey::RSA.new(File.read('private.pem'))

signed_string = "(request-target): post /inbox\nhost: mastodon.social\ndate: #{date}"

signature = Base64.strict_encode64(keypair.sign(OpenSSL::Digest::SHA256.new, signed_string))

header = 'keyId="https://my-example.com/actor",headers="(request-target) host date",signature="' + signature + '"'

HTTP.headers({ 'Host': 'mastodon.social', 'Date': date, 'Signature': header })

.post('https://mastodon.social/inbox', body: document)

Let’s save it as deliver.rb. I am using the HTTP.rb gem here, so you’ll need to have that installed (gem install http). Finally, run the file with ruby deliver.rb, and your message should appear as a reply on my toot!

Mellotron singing synthesizer using CPU

Insallation

Download pretrained model checkpoints from nvidia/mellotron repository and specify the paths here

Usage

Check this Google Colab.

About musicXML Format

- The characters must be in [a-zA-Z]

- Each word must start with an upper case

- Every word must exist in the cmu_dictionary dictionary. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ARPABET

Relevant notes 1

In reference to the GST part of mellotron, there is no 1:1 lock. You can use GST the same way as in other repos.

If you want to do inference with the mellotron model however, we additionally extract two things from a reference audio: the rhythm and the pitch which creates the 1:1 correspondence. It’s the rhythm that creates the 1:1 correspondence actually. But your automatically-extracted pitch might not make sense if you do not additionally condition on the rhythm.

If you don’t want rhythm (which you can disable by using model.inferece()) and pitch conditioning (which you can disable by sending zeros as the pitch), you get essentially tacotron 2 with GST and speaker ids.

Relevant notes 2

The paper states that “the target speaker, St, would always be found in the training set, while the source text, pitch and rhythm (Ts, Ps, Rs) could be from outside the training set.” so I presume there is no need for speaker ids for source audios – it doesn’t make sense after all for some arbitrary input audio outside the training set to have a valid speaker id. However in the examples_filelist.txt there is a column for speaker ids. What is the significance of this column?

The model expects a speaker id, so we give it a random speaker id.

Conclusion

We have covered how to create a discoverable ActivityPub actor and how to send replies to other people. But there is a lot we haven’t covered: How to follow and be followed (it requires a working inbox), how to have a prettier profile, how to support document forwarding with LD-Signatures, and more. If there is demand, I will write more in-depth tutorials!