Dysphotopsia means unwanted visual images or disturbances that a person sees, usually after cataract surgery when an artificial lens (intraocular lens, IOL) is placed inside the eye. These are not “real” objects in the world but artifacts created by the way light travels through or around the lens and eye structures, producing glare, shadows, streaks, or missing patches of vision. Dysphotopsias are one of the common causes of patient dissatisfaction even after an otherwise successful cataract surgery. They can be temporary for many people, but in a minority they persist and may need further evaluation or treatment. PMC EyeWiki American Academy of Ophthalmology

Dysphotopsia is an unwanted visual problem that some people get after cataract surgery when an artificial lens (intraocular lens or IOL) is put into the eye. Instead of seeing a normal clear image, they notice strange light effects. These might be extra lights, bright streaks, rings, shadows, or dark arcs that are not really there in the outside world but appear inside the eye. These visual disturbances can make people worried, annoyed, or feel like their surgery did not work well even when everything is medically fine. Dysphotopsia is split into two main kinds: positive and negative. Positive dysphotopsia means extra light effects like glare, streaks, or halos. Negative dysphotopsia means seeing a dark shadow or missing part of vision, usually at the edge of what you see. These problems are among the most common sources of patient dissatisfaction after otherwise successful cataract surgery. PMC EyeWiki

Types of Dysphotopsia

There are two main types, plus a related variant that is usually grouped in clinical discussions:

- Positive dysphotopsia is when the patient sees extra light phenomena. These include bright arcs, streaks, starbursts, halos, rings, glare, or flashes that are not actually in the environment but appear when light enters the eye. Patients often describe these as bothersome “flares” around lights, especially in certain angles or lighting conditions. PMCResearchGateeyeworld.org

- Negative dysphotopsia is when part of the visual field seems to be missing—a dark crescent or shadow, typically in the temporal (side) part of vision. It is not a blur but a localized absence of light, often described as a “door frame” or “shadow” on the outer edge of vision. EyeWikiScienceDirect

- Multifocal/diffractive dysphotopsia is a variation seen particularly with multifocal or diffractive IOLs. It combines features of positive dysphotopsia—like halos and glare—but arises from the intentional optical splitting of light in those lens designs. It is sometimes treated as its own category because the mechanism (diffractive optics) is distinct. PentaVision

Mixed/Overlap Dysphotopsia: Some patients may experience both positive and negative symptoms, or multiple optical aberrations at once, especially if they have complex lens designs (e.g., multifocal or high-index lenses), irregular ocular surfaces, or combined anatomical predispositions. CRSToday

Transient vs Persistent: Many dysphotopsias, especially mild positive ones, improve over weeks to months as the brain adapts (neuroadaptation) or as capsular healing alters light paths. Persistent cases may last longer and sometimes require intervention. ScienceDirect

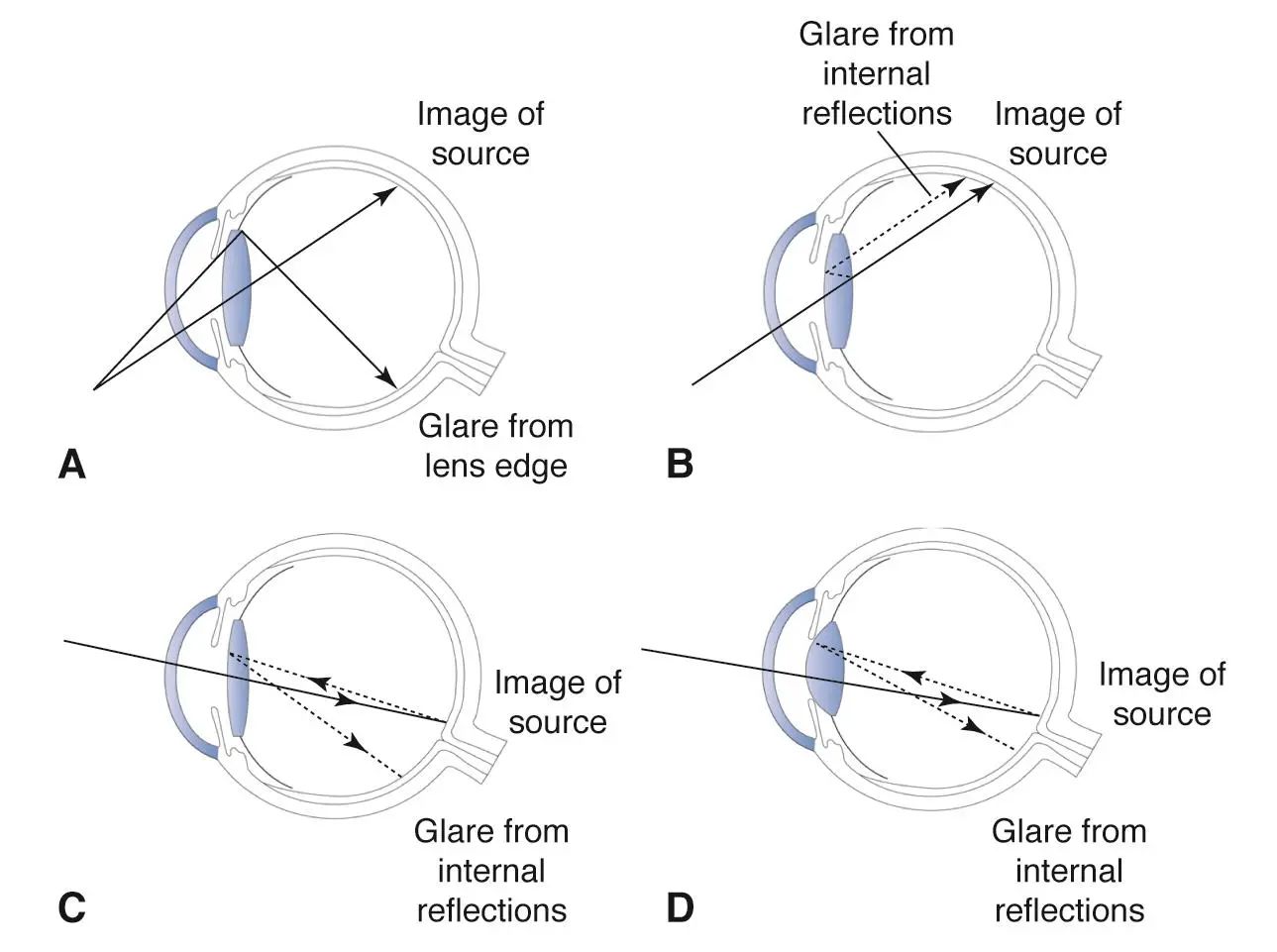

The mechanisms differ: positive dysphotopsia arises from stray light or internal reflections creating additional bright images, while negative dysphotopsia seems to result from specific pathways of light being excluded from the peripheral retina, producing a shadow. PMCScienceDirect

Causes of Dysphotopsia

Below are 20 causes or contributing factors. Some are directly responsible for dysphotopsia, and others are common mimics or risk modifiers that must be considered in the evaluation.

Square-edge IOL design: Many modern IOLs have a sharp square edge intended to reduce posterior capsule opacification, but that edge can cause internal light reflections leading to positive dysphotopsia. eyeworld.org

High refractive index of the IOL material: Lenses with a higher refractive index can increase internal reflection or scattering, making positive dysphotopsias more likely. eyeworld.org

Decentration or tilt of the IOL: If the lens sits slightly off-center or tilted, light can enter and refract in unexpected ways, creating ghost images, streaks, or shadows. PMCResearchGate

Capsulorhexis size and overlap: A capsulotomy (the opening in the lens capsule made at surgery) that is too small or overlaps improperly with the IOL optic can change the light path and contribute to negative dysphotopsia or edge effects. ResearchGate

Large pupil in dim light: A dilated pupil changes how peripheral rays enter the eye and can exaggerate glare, halos, or the perception of shadows, making both positive and negative phenomena more noticeable. AAO Journal

Anterior capsule anatomy or residual capsule tissue: Irregularities in the capsular bag or remaining capsular folds can interact with the IOL edge and light path, contributing to symptoms. ResearchGate

Posterior capsule opacification (PCO): Though typically a later complication, opacification causes scattering of light, which can mimic or worsen positive dysphotopsia by introducing glare and halos. AAO Journal

IOL optic size and peripheral geometry: Smaller optics or unusual edge profiles can cause light to fall off the retina peripherally, sometimes perceived as negative dysphotopsia. ScienceDirect

Anterior segment anatomical variations (angle kappa, axial length): Individual eye geometry like a large angle kappa or long axial length can shift the effective path of light and influence the appearance of dysphotopsias. ResearchGate

Multifocal and diffractive IOL optics: Intentional splitting of light in these designs leads to overlapping images and “glare-like” artifacts that are functionally a form of dysphotopsia. PentaVision

Corneal irregularities (e.g., scars, irregular astigmatism): Surface irregularities scatter incoming light and create starbursts or halos similar to positive dysphotopsia, often worsening after surgery if not addressed. Wikipedia

Dry eye or tear film instability: A poor tear film creates fluctuating optics, causing transient glare, haloes, and decreased contrast that patients may describe as dysphotopsia. NCBI

Early or residual cataract changes (if hybrid or not fully cleared): Lens changes not completely removed or early posterior subcapsular changes can cause scattering and light artifacts. (Clinical context general ophthalmic knowledge supported by comprehensive exam guidelines). American Orthopaedic Association

Vitreous floaters or posterior vitreous detachment: Though not true dysphotopsia from IOL optics, shadows or transient dark shapes from vitreous changes can be mistaken for negative dysphotopsia. American Orthopaedic Association

Retinal pathologies (e.g., retinal tears, detachment, epiretinal membrane): These can produce shadows, missing areas, or distortion that overlap with negative dysphotopsia symptoms, making careful differentiation important. American Orthopaedic Association

Macular disease (e.g., age-related macular degeneration): Central visual distortion, scotomas, or decreased contrast from macular issues can coexist or mimic the complaints of dysphotopsia. American Orthopaedic Association

Optic nerve disease (e.g., optic neuritis, glaucoma field defects): Vision field defects or transient visual blurring from optic nerve problems may be confused with peripheral shadows or missing areas. American Orthopaedic Association

Neurological visual phenomena (e.g., migraine aura, occipital lobe lesions): Transient bright lights, zig-zags, or patches can resemble positive or negative dysphotopsia but stem from cortical processing rather than intraocular optics. ScienceDirect

Systemic medications (e.g., digoxin): Some drugs can cause visual halos or color disturbances that patients might describe as dysphotopsia-like—reviewing medication history and levels is essential. NCBI

Inflammation or uveitis: Inflammatory cells or debris in the anterior or posterior segment can scatter light causing glare or non-specific optical artifacts that resemble positive dysphotopsia. American Orthopaedic Association

Symptoms of Dysphotopsia

Patients describe a variety of visual experiences. Here are 15 common symptoms, which may overlap depending on type:

Glare – Bright, uncomfortable light, especially from oncoming headlights or sunlight, that seems to wash out vision. PMC

Halos – Rings of light around bright sources, often seen at night or in low light. EyeWiki

Starbursts – Spiky rays radiating from lights, resembling a star; typical in positive dysphotopsia. PMC

Light streaks or arcs – Lines or curved bands of light that should not be present, often seen when bright light enters the eye at certain angles. ResearchGate

Bright spots or flashes – Sudden flashes or glowing spots unrelated to actual movement in the environment. EyeWiki

Dark temporal shadow (arc or crescent) – A missing area or shadow on the outer side of vision, hallmark of negative dysphotopsia. ScienceDirect

Peripheral shadowing – Subtle or pronounced darkening at the edge of vision, sometimes described as a “frame” or “curtain.” ScienceDirect

Ghost images / double vision – Secondary faint images overlapping the true image, caused by internal reflections or optical overlap. PMC

Decreased contrast sensitivity – Things look washed out, making it harder to differentiate shades, often noted in bright or low-light conditions. AAO Journal

Difficulty with night driving – Complaints of poor visibility or excessive light scatter when driving in the dark. AAO Journal

Image distortion – Shapes or lights that seem slightly warped or not true to form, sometimes overlapping with other ocular disease effects. American Orthopaedic Association

Transient visual “flicker” or shimmering – Short bursts where lights appear to flicker or ripple oddly. Review of Ophthalmology

Sensitivity to bright lights (photophobia) – Uncomfortable reaction to normal lighting that feels exaggerated. NCBI

Perception of a “cut-out” or missing slice in vision – A more global sense that part of the visual field is absent, related to negative dysphotopsia. ScienceDirect

Persistent awareness of visual artifact despite good acuity – Patients may have 20/20 vision yet still feel something is wrong because the artifact does not degrade clarity but is distracting. Review of Ophthalmology

Diagnostic Tests

A careful, structured evaluation helps confirm dysphotopsia and rule out mimics. Below are 20 commonly used tests, grouped and explained.

Physical Examination

Visual acuity testing (distance and near) – Basic measure of how well the patient sees; often normal in dysphotopsia but needed to document baseline and rule out gross visual loss. AAO JournalAmerican Orthopaedic Association

Refraction (manifest or cycloplegic) – Determines whether residual refractive error is contributing to symptoms like glare or halos. American Orthopaedic Association

Slit-lamp biomicroscopy – Examines the front of the eye, the IOL position, capsular overlap, and the clarity of media to identify lens issues or early PCO. NCBIAmerican Orthopaedic Association

Dilated fundus examination – Rules out retinal causes (tears, detachments, macular problems) that could mimic or coexist with dysphotopsia. American Orthopaedic Association

Pupillary exam (size and reactivity) – Assesses for abnormal pupil behavior that could change how light enters the eye or indicate neurological issues. American Orthopaedic Association

Manual / Functional Tests

Contrast sensitivity testing – Detects reduced ability to distinguish shades, which patients often report as part of their dysphotopsia experience even with normal acuity. AAO Journal

Glare testing – Simulates bright light conditions to quantify how much glare impairs vision; helps correlate patient complaints with measurable performance changes. Aetna

Amsler grid – Screens for macular distortion or scotomas that could explain some visual complaints rather than true optical dysphotopsia. American Orthopaedic Association

Shadow mapping / localized visual field testing for negative dysphotopsia – Patient outlines where they perceive the dark arc/shadow, helping to document its location and consistency. ResearchGate

Pupil size measurement under different lighting – Helps understand whether pupil dynamics are amplifying optical artifacts (e.g., large under scotopic conditions). AAO Journal

Laboratory / Pathological Evaluation

Blood glucose / HbA1c – Diabetes can cause retinal changes; checking glucose control helps rule out diabetic retinopathy as a cause of visual artifacts. American Orthopaedic Association

Inflammatory and autoimmune markers (e.g., CRP, ESR, ANA, HLA-B27) – If intraocular inflammation or uveitis is suspected, these help identify systemic causes that could scatter light or cause secondary optical symptoms. American Orthopaedic Association

Serum drug levels / medication review – Some systemic drugs (like digoxin) can cause visual halos or color changes; confirming exposure or level can explain symptoms. NCBI

Electrodiagnostic Tests

Visual evoked potentials (VEP) – Measures the electrical response of the visual cortex to stimuli; useful if a neurological cause (optic nerve or cortical) is suspected in the differential. American Orthopaedic Association

Electroretinography (ERG) – Tests retinal function; helps rule out primary retinal dysfunction that might mimic or contribute to the patient’s symptom profile. American Orthopaedic Association

Imaging Tests

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) of macula and optic nerve – High-resolution cross-sectional images to exclude macular disease or optic nerve swelling that could explain visual complaints. MDPI

Anterior segment OCT or Scheimpflug imaging – Visualizes IOL position, edge interactions, and capsular anatomy; helps identify mechanical explanations for dysphotopsia. MDPI

Ultrasound B-scan – Used when media are cloudy or to evaluate posterior segment pathology like retinal detachment when direct visualization is limited. American Orthopaedic Association

Fundus photography – Documents retinal appearance over time, helps track any subtle changes that might contribute to symptoms or differentiate from true optical dysphotopsia. American Orthopaedic Association

Wavefront aberrometry – Measures higher-order optical aberrations of the eye, revealing subtle imperfections and how the light is distorted, which can correlate with patients’ subjective glare, starbursts, or halos. Lippincott JournalsResearchGate

Non-Pharmacological Treatments

Patient Education and Reassurance – Explaining that mild dysphotopsia often improves with time reduces anxiety, aiding neuroadaptation. Purpose: reduce focus on symptoms; Mechanism: psychological reframing and brain adaptation. ScienceDirect

Observation / Watchful Waiting – Many mild positive symptoms fade over 3–12 months as neuroadaptation occurs. Purpose: avoid unnecessary intervention; Mechanism: cortical adaptation to new optics. ScienceDirect

Optical Simulation (e.g., trial glasses with small pupil effect) – Using filters or glasses to simulate pupil constriction can temporarily reduce perception of dysphotopsia. Purpose: symptom relief; Mechanism: limits peripheral light entry that creates edge artifacts. CRSToday

Pupil Modulation with Miotic Glasses or Low-Dose Pilocarpine (off-label) – Reduces effective aperture to decrease peripheral edge effects. Purpose: reduce stray light; Mechanism: smaller pupil limits rays causing positive dysphotopsia. (Note: patient must be evaluated for side effects like brow ache.) CRSToday

IOL Reorientation Techniques (e.g., reverse optic capture) – Surgical adjustment of IOL optic relative to capsulorhexis to change light paths. Purpose: treat negative dysphotopsia; Mechanism: alters relation so the optic overlaps anterior capsule preventing illumination gap. ScienceDirect

Supplementary IOL Implantation (e.g., Sulcoflex in sulcus) – Adds an additional optic to modify light flow and mask shadows. Purpose: mitigate persistent negative dysphotopsia; Mechanism: changes effective geometry of light entering retina, filling the perceived gap. PMC

IOL Exchange (to different edge design or material) – Remove original IOL and replace with one less likely to cause dysphotopsia (e.g., round-edge or different optic). Purpose: eliminate causative optics; Mechanism: new lens has different reflection/edge properties. ascrs.org

Nd:YAG Laser Anterior Capsulotomy or Capsular Modification – Creating or adjusting the capsular edge to reduce a clear edge causing negative dysphotopsia. Purpose: treat ND; Mechanism: opacifying or altering capsule blur the sharp illumination gap. ScienceDirect

Contact Lens with Peripheral Occlusion – Temporarily masking peripheral light entry (used diagnostically and sometimes therapeutically) to see if shadow improves. Purpose: diagnostic confirmation; Mechanism: blocks offending rays.

Surface Optimization before and after Surgery (dry eye treatment, eyelid hygiene) – Ensures clean optical surface so patients don’t misinterpret ocular surface aberrations as dysphotopsia. Purpose: reduce confounding factors; Mechanism: smoother tear film reduces scatter. PMC

Use of Anti-Glare or Polarized Glasses – Helps patients in bright or nighttime environments by reducing incoming stray light. Purpose: comfort; Mechanism: cuts glare and light scatter entering eye. CRSToday

Adjusting IOL Haptic Orientation – Sometimes rotating a lens changes its interaction with capsule anatomy and can reduce symptoms. Purpose: symptom mitigation; Mechanism: alters positional light geometry. eyeworld.org

Neurovisual Rehabilitation / Vision Therapy (focused attention exercises) – Train brain to de-emphasize the unwanted image. Purpose: help neuroadaptation; Mechanism: perceptual learning to suppress awareness. ScienceDirect

Lighting Environment Optimization – Advising patients to avoid harsh or contrasty lighting that exaggerates dysphotopsia. Purpose: reduce triggers; Mechanism: less high-contrast stimulus reduces visibility of artifacts. CRSToday

Use of Tinted or Yellow Lenses – Filters certain wavelengths or reduces glare sensation. Purpose: comfort in bright light; Mechanism: spectral filtering minimizes bright artifact perception. CRSToday

Capsule Fibrosis Encouragement (natural healing) – In select ND, allowing mild opacification of anterior capsule (without intervention) to blur gap; the surgeon might delay aggressive polishing. Purpose: self-limited improvement; Mechanism: slight scattering fills illumination gap. ScienceDirect

Alternative IOL Designs at Initial Surgery (prevention, but mention here for early cases) – Choosing lenses known to have lower dysphotopsia rates. Purpose: reduce chance of future symptoms; Mechanism: smoother edges, material choice. CRSToday

Standardized Symptom Tracking and Questionnaires – Helps quantify and communicate problems to surgeon so appropriate interventions can be chosen. Purpose: better management; Mechanism: structured feedback facilitates decision making. ScienceDirect

Delayed Intervention Protocols – Wait 3–6 months to see if symptoms resolve before surgical steps unless severe. Purpose: avoid overtreatment; Mechanism: time allows neuroadaptation and capsular changes. ScienceDirect

Combining Multiple Non-invasive Strategies – Using education, optical aids, and surface therapy together often gives additive benefit. Purpose: holistic relief; Mechanism: addresses multiple contributing factors simultaneously. ScienceDirectCRSToday

Drug Treatments

Note: There is no medication that directly “cures” dysphotopsia because it is primarily optical/structural. However, these drugs treat inflammation, ocular surface issues, or secondary conditions that can worsen or mimic dysphotopsia.

Topical Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) – Bromfenac 0.07% or 0.1%

Class: NSAID eye drop

Dosage/Time: Typically one drop twice daily starting before or immediately after surgery for 2–4 weeks.

Purpose: Reduce ocular inflammation and prevent cystoid macular edema which can worsen glare/visual aberrations.

Mechanism: Blocks prostaglandin synthesis, reducing inflammation and vascular leakage.

Side Effects: Stinging, delayed epithelial healing rarely, surface irritation. PMC

Topical NSAID – Ketorolac tromethamine 0.5%

Class: NSAID

Dosage: One drop 4 times daily around cataract surgery period.

Purpose: Same as above; reduce postoperative inflammation, minimize light scatter from macular changes.

Mechanism: Cyclooxygenase inhibition preventing prostaglandin-mediated inflammation.

Side Effects: Burning sensation, corneal complications if overused in compromised epithelium. California Optometric Association

Topical Corticosteroid – Prednisolone acetate 1%

Class: Steroid

Dosage: Often multiple times daily after surgery, tapered over weeks per protocol.

Purpose: Control postoperative inflammation to reduce secondary visual disturbances.

Mechanism: Inhibits inflammatory gene transcription and cytokine production.

Side Effects: Increased intraocular pressure, cataract formation (not relevant post-op lens already implanted), infection risk if misused. ESCRS

Topical Corticosteroid – Loteprednol etabonate (e.g., 0.5%)

Class: Soft steroid

Dosage: According to surgeon protocol, often gradually tapered.

Purpose: Mild inflammation control with lower pressure rise risk.

Mechanism: Similar to prednisolone but metabolized quickly to inactive form.

Side Effects: Less risk of elevated pressure but possible transient irritation. ESCRS

Artificial Tears (Preservative-free lubricants)

Class: Ocular surface lubricant

Dosage: As needed, often multiple times per day.

Purpose: Optimize tear film to reduce surface-induced aberrations that can mimic dysphotopsia.

Mechanism: Provide hydration and smooth optical surface.

Side Effects: Minimal; rare allergy to components. PMC

Topical Cyclosporine A (e.g., 0.05%)

Class: Immunomodulator

Dosage: Typically twice daily long-term for dry eye.

Purpose: Treat underlying ocular surface inflammation and chronic dry eye that can exacerbate visual symptoms.

Mechanism: Reduces T-cell mediated inflammation improving tear film stability.

Side Effects: Burning on instillation, transient blurred vision. (Indirectly helps dysphotopsia by improving surface) PMC

Topical Lifitegrast

Class: Lymphocyte function–associated antigen-1 (LFA-1) antagonist

Dosage: Twice daily

Purpose: Chronic dry eye treatment to optimize ocular optics.

Mechanism: Blocks inflammation at ocular surface by inhibiting T-cell adhesion.

Side Effects: Dysgeusia, burning sensation. PMC

Low-Dose Pilocarpine (off-label for pupil modulation)

Class: Miotic

Dosage: Typically 1% drop once daily or lower concentration at night.

Purpose: Reduce pupil diameter to limit peripheral optical artifact exposure.

Mechanism: Constricts pupil (muscarinic agonist), decreasing aberrant light rays reaching retina.

Side Effects: Brow ache, reduced night vision, risk of anterior chamber angle closure in predisposed eyes. CRSToday

Oral Omega-3 Fatty Acids (as adjunct to ocular surface health)

Class: Nutraceutical

Dosage: 1000–3000 mg/day EPA/DHA combined

Purpose: Improve tear quality and reduce inflammation that can contribute to surface irregularities.

Mechanism: Anti-inflammatory lipid mediators derived from omega-3s modulate ocular surface inflammation.

Side Effects: Fishy aftertaste, gastrointestinal upset. PMC

Adjunctive Low-dose Oral Anti-inflammatory Agents (e.g., short course of oral NSAIDs if recommended by physician)

Class: Systemic NSAID

Dosage: Standard per agent (e.g., ibuprofen 200–400 mg every 6–8 hours) for brief course.

Purpose: Supplemental inflammation control when topical treatment insufficient or combined pathology.

Mechanism: Systemic prostaglandin suppression.

Side Effects: GI irritation, kidney stress in susceptible individuals. (Use cautiously.) ESCRS

Dietary Molecular Supplements

Lutein (10–20 mg/day)

Function: Protects macular health and filters blue light.

Mechanism: Accumulates in macula as pigment, reducing oxidative stress and improving contrast.

Dosage: Commonly 10 mg/day in supplement form.

Benefit: May improve visual quality indirectly reducing perception of glare. EyeWiki

Zeaxanthin (2 mg/day)

Function: Synergizes with lutein for macular pigment density.

Mechanism: Antioxidant filtering of short wavelength light, improving visual clarity.

Dosage: 2 mg/day. EyeWiki

Omega-3 Fatty Acids (EPA/DHA 1000–3000 mg/day)

Function: Supports tear film, reduces ocular inflammation.

Mechanism: Converts to anti-inflammatory mediators, improves meibomian gland function.

Dosage: 1–3 grams combined EPA/DHA daily. PMC

Vitamin C (500–1000 mg/day)

Function: Antioxidant protection for ocular tissues.

Mechanism: Scavenges free radicals, supports collagen synthesis for scleral and corneal health.

Dosage: 500–1000 mg twice daily depending on diet. ESCRS

Vitamin E (100 IU/day)

Function: Lipid-soluble antioxidant protecting cell membranes.

Mechanism: Prevents peroxidation of polyunsaturated fats in ocular cells.

Dosage: 100 IU/day. ESCRS

Zinc (25–40 mg/day)

Function: Supports retinal enzyme systems and antioxidant defenses.

Mechanism: Cofactor for superoxide dismutase and others; helps stabilize macular pigments.

Dosage: 25–40 mg/day with copper to avoid imbalance. ESCRS

Astaxanthin (4–12 mg/day)

Function: Potent antioxidant protecting against light-induced damage and improving visual fatigue.

Mechanism: Crosses blood-retina barrier; quells oxidative stress in photoreceptors.

Dosage: 4–12 mg/day. MDPI

Bilberry Extract (standardized to anthocyanins, 80–160 mg/day)

Function: May improve night vision and reduce glare sensitivity.

Mechanism: Antioxidant flavonoids support capillary integrity and reduce oxidative stress.

Dosage: 80–160 mg/day. EyeWiki

N-Acetylcysteine (600–1200 mg/day)

Function: Mucolytic and antioxidant for ocular surface.

Mechanism: Precursor to glutathione, reduces oxidative stress, improves tear film.

Dosage: 600 mg twice daily. PMC

Alpha-Lipoic Acid (300–600 mg/day)

Function: Broad-spectrum antioxidant benefiting neural and ocular tissues.

Mechanism: Regenerates other antioxidants (vitamin C, E) and reduces inflammatory cascades.

Dosage: 300 mg twice daily. MDPI

Regenerative / Stem Cell / “Hard Immunity” Related Biologic Therapies

Note: Dysphotopsia itself is not an immune disease; these regenerative approaches support ocular surface and nerve health, indirectly helping visual quality and patient tolerance.

Autologous Serum Eye Drops (20% concentration typical)

Dosage: 4–8 times daily as needed for ocular surface disorders.

Function: Heals and stabilizes corneal surface, improving optical quality.

Mechanism: Contains growth factors, vitamins, and proteins similar to natural tears; promotes epithelial health and reduces inflammation.

Evidence: Effective for severe ocular surface disease and may reduce aberrations that mimic dysphotopsia. PubMedMDPI

Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) Eye Drops

Dosage: Frequency varies (often 3–6 times daily).

Function: Accelerates healing of ocular surface and increases tear film quality.

Mechanism: Concentrated platelets release growth factors (PDGF, TGF-β) promoting epithelial restoration.

Evidence: Comparisons show benefit in dry eye and surface health, potentially reducing visual complaints. Wiley Online Library

Cenegermin (Recombinant Human Nerve Growth Factor)

Dosage: Typically one drop six times daily for 8 weeks (approved for neurotrophic keratitis).

Function: Regenerates corneal nerves and improves ocular surface sensation.

Mechanism: Stimulates nerve growth, supporting tear reflex and epithelial maintenance.

Indirect Benefit: Better ocular surface reduces noise contributing to subjective visual disturbances. ScienceDirect

Amniotic Membrane Biological Therapy (e.g., ProKera)

Dosage: Applied as a temporary insert for days to weeks depending on indication.

Function: Provides a healing environment for the ocular surface, reduces inflammation, and supports epithelialization.

Mechanism: Suppresses fibrosis and inflammation while delivering growth factors.

Benefit: Improves surface smoothness and reduces secondary aberrations. ScienceDirect

Mesenchymal Stem Cell–Derived Exosomes / Experimental MSC Therapy for Ocular Surface

Dosage: Investigational; delivered topically or via supportive scaffolds in research settings.

Function: Anti-inflammatory, regenerative support to damaged epithelial or stromal cells.

Mechanism: Exosomes carry microRNAs and proteins that modulate immune response and promote healing.

Status: Emerging research suggests potential for chronic surface disease. ScienceDirect

Autologous Limbal Stem Cell Transplant (for severe surface disease)

Dosage: Surgical harvest and transplant with postoperative supportive therapy.

Function: Restores epithelial stem cell population in damaged corneas.

Mechanism: Re-establishes normal corneal epithelium, improving transparency and surface regularity.

Indirect Benefit: Smoother and healthier surface reduces spurious visual phenomena. ScienceDirect

Surgical Procedures

Intraocular Lens (IOL) Exchange

Procedure: Remove the existing lens and replace it with a different design (e.g., round-edge, different material, or optic size).

Why Done: Persistent positive or negative dysphotopsia that does not resolve, thought to be due to the optical properties or edge design of the original IOL.

Goal: Eliminate causative light reflections or shadows. ascrs.org

Reverse Optic Capture (ROC)

Procedure: Surgically position the IOL optic anterior to the capsulorhexis while keeping haptics in the bag, creating an overlap to modify light path.

Why Done: Specifically for negative dysphotopsia from illumination gaps; changes the relationship between capsule and optic to reduce shadow. ScienceDirect

Supplementary Sulcus IOL Implantation (e.g., Sulcoflex)

Procedure: Implant a secondary lens in the sulcus to alter the optical system without removing the primary IOL.

Why Done: Addresses persistent negative dysphotopsia by reshaping the light entering the eye and filling the perceived gap. PMC

Nd:YAG Laser Anterior Capsulotomy / Capsular Modification

Procedure: Use laser to create a small opening or induce controlled opacification of the anterior capsule near the optic edge.

Why Done: For negative dysphotopsia when a sharp, clear capsule edge is contributing to the shadow; blurring that edge can relieve symptoms. ScienceDirect

Capsular Overlap Adjustment (Surgical Capsulorhexis Tactics)

Procedure: During initial surgery or revision, ensure that the anterior capsulotomy overlaps the IOL optic margin adequately, or surgically modify to achieve desired coverage.

Why Done: Prevent or treat negative dysphotopsia by smoothing or changing the capsule-optic interface. ScienceDirect

Prevention Strategies

Careful IOL Selection – Choose lenses known to minimize dysphotopsia risk (e.g., round-edge vs square-edge depending on patient anatomy). CRSToday

Optimize Ocular Surface Before Surgery – Treat dry eye, blepharitis, and other surface conditions so the post-op optics are clean. PMC

Ensure Adequate Capsulorhexis Overlap on Optic – Proper sizing and centration helps avoid illumination gaps for ND. ScienceDirect

Patient Counseling and Expectation Management – Inform patients about possible dysphotopsia and typical course so they are less alarmed. ScienceDirect

Avoid Multifocal IOLs in High-Risk Eyes Without Discussion – Recognize that diffractive optics raise risk of positive dysphotopsia. CRSToday

Use of Anti-inflammatory Prophylaxis (Topical NSAID + Steroid) – Prevent inflammation and CME to reduce secondary visual distortions. ESCRS

Meticulous Surgical Technique (Cleaning Residual Cortex) – Reduces post-op scatter and visual complaints. CRSToday

Appropriate Pupil Consideration (Avoiding Extreme Dilation at Critical Steps) – Recognize pupil dynamics that could exacerbate edge effects. CRSToday

Assess Preoperative Anatomy (e.g., nasal retina function, iris defects) – Identify patients more likely to perceive shadows and plan accordingly. ScienceDirect

Follow Evidence-Based Post-Op Protocols for Inflammation Control – Use guidelines to manage inflammation comprehensively. ESCRS

When to See a Doctor

You should contact your eye doctor if any of these occur:

Dysphotopsia persists beyond 6 months without improvement and interferes with daily life. ScienceDirect

Sudden increase in severity of visual disturbances. AAO Journal

New floaters or flashes of light accompany the symptom, which could signal retinal issues. AAO Journal

Decreased vision or blurred vision beyond normal post-surgery recovery. AAO Journal

Eye pain, redness, or discharge suggesting infection or severe inflammation. AAO Journal

Signs of cystoid macular edema (e.g., central blur, distortion). CRSToday

Perceived shift in lens position or double vision indicating possible IOL tilt or decentration. ascrs.org

No adaptation after several months despite reassurance and conservative measures. ScienceDirect

Worsening glare affecting night driving or safety. eyeworld.org

Any new concerning symptoms outside expected recovery. AAO Journal

What to Eat and What to Avoid

What to Eat (Support Eye Health and Reduce Inflammation):

Leafy Greens (spinach, kale) – High in lutein and zeaxanthin for macular health. EyeWiki

Eggs – Good source of lutein/zeaxanthin with high bioavailability. EyeWiki

Fatty Fish (salmon, sardines) – Rich in omega-3s for ocular surface and anti-inflammatory support. PMC

Citrus fruits – Vitamin C to protect against oxidative damage. ESCRS

Nuts and seeds (almonds, sunflower seeds) – Provide vitamin E and zinc. ESCRS

Colorful berries – Anthocyanins and antioxidants support microvascular health. EyeWiki

Legumes (beans, lentils) – Zinc and other micronutrients for retinal function. ESCRS

Whole grains – Help systemic inflammation control through stable blood sugar. MDPI

Green tea – Polyphenols with antioxidant benefits. MDPI

Hydration (water) – Maintains tear film and ocular surface health. PMC

What to Avoid:

Smoking – Increases oxidative stress and damages ocular tissues. ESCRS

Excessive sugar/high-glycemic foods – Promote systemic inflammation. MDPI

Trans fats and highly processed foods – Encourage vascular and inflammatory stress. MDPI

Excessive alcohol – Can dehydrate and worsen tear film instability. PMC

High-sodium diets – May affect blood pressure and ocular microcirculation. MDPI

Overconsumption of caffeine (in sensitive individuals) – May affect tear production or cause dehydration. PMC

Skipping omega-3s in diet – Missing anti-inflammatory support; avoid deficiency. PMC

Ignoring poor nutrition in recovery period – Can delay healing and worsen symptom perception. MDPI

Self-medicating with unverified eye drops – Risk of toxicity or contamination. PMC

Extreme dieting leading to nutrient deficiency – May lower macular pigment and antioxidant defenses. ESCRS

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the difference between positive and negative dysphotopsia?

Positive means seeing extra light artifacts (halos, streaks); negative means a dark shadow or missing area in vision. EyeWikiScienceDirectWill dysphotopsia go away on its own?

Mild cases, especially positive dysphotopsia, often improve over months due to brain adaptation and capsular healing. ScienceDirectWhen is surgery needed for dysphotopsia?

If symptoms persist, are severe, or do not improve after 6 months and significantly affect quality of life, surgical options like IOL exchange or ROC can be considered. ascrs.orgScienceDirectCan glasses help with dysphotopsia?

Yes. Polarized or tinted glasses and optical simulation (e.g., limiting glare) can reduce symptoms from positive dysphotopsia. CRSTodayIs dysphotopsia permanent?

Not always. Some cases resolve; persistent or anatomy-related ones may need interventions. ScienceDirectDo certain IOL types cause more dysphotopsia?

Multifocal and sharp-edged high-index lenses have higher risk of positive and/or negative dysphotopsia. Proper selection reduces risk. CRSTodayCRSTodayCan dry eye make dysphotopsia worse?

Yes. Surface irregularity can mimic or amplify the perception; treating dry eye often helps. PMCWhat tests will the doctor do for dysphotopsia?

History, slit-lamp, visual fields, OCT, contrast/glare testing, and capsular-IOL relationship assessments. ScienceDirectAre supplements helpful?

Supplements like lutein, zeaxanthin, omega-3s, zinc, and antioxidants support overall eye health and may indirectly improve symptom tolerance. EyeWikiPMCCan I prevent dysphotopsia before cataract surgery?

Yes—optimize ocular surface, choose appropriate IOL, ensure good surgical technique, and counsel patients. CRSTodayPMCWhat is reverse optic capture and when is it used?

A surgical technique to change IOL positioning to treat negative dysphotopsia by overlapping the capsule and optic. ScienceDirectWill an IOL exchange fix dysphotopsia?

It can if the original lens optics or edges are the cause; success depends on correct new lens choice and patient factors. ascrs.orgIs there a pill that cures dysphotopsia?

No direct cure exists. Medicines treat underlying inflammation or surface disease but do not remove optical artifacts from lens edges. ESCRSScienceDirectWhat if dysphotopsia appears suddenly after being fine?

Sudden change warrants evaluation to rule out other causes like retinal issues or lens displacement. AAO JournalCan the brain learn to ignore the symptoms?

Yes — neuroadaptation is a key reason mild dysphotopsia improves over time without intervention. ScienceDirect

Disclaimer: Each person’s journey is unique, treatment plan, life style, food habit, hormonal condition, immune system, chronic disease condition, geological location, weather and previous medical history is also unique. So always seek the best advice from a qualified medical professional or health care provider before trying any treatments to ensure to find out the best plan for you. This guide is for general information and educational purposes only. Regular check-ups and awareness can help to manage and prevent complications associated with these diseases conditions. If you or someone are suffering from this disease condition bookmark this website or share with someone who might find it useful! Boost your knowledge and stay ahead in your health journey. We always try to ensure that the content is regularly updated to reflect the latest medical research and treatment options. Thank you for giving your valuable time to read the article.

The article is written by Team RxHarun and reviewed by the Rx Editorial Board Members

Last Updated: August 02, 2025.